By AO Scott (The New York Times)

Translator: csh

The translation was first published in "Iris"

According to tradition, a story that ends in marriage is classified as a comedy. So what if a story begins with the end of a marriage? Noah Baumbach's tender and disturbing new "Marriage Story" doesn't quite address the issue. It is both joyful and sad, and sometimes a single scene is enough to have both. It presents the messy disintegration of a shared life and weaves a complex plot out of it, and it tries to create music out of dissonance. Its melody is full of grief, loss and regret, but the song is so beautiful that it transcends that melancholic quality.

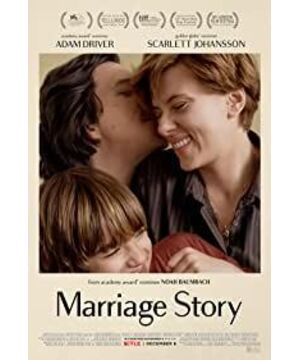

Charlie (Adam Driver) and Nicole (Scarlett Johansson) are a Brooklyn-based literary couple with an eight-year-old son Henry (Edge Robertson) quiet performance). Both husband and wife work in the film industry: Nicole, a former teenage movie star (she is also a Hollywood daughter), is now the lead actor of an experimental troupe, and Charlie is the director of the troupe, but he occasionally will act. What we know about their lives together is based on an opening montage in which the two list the traits they love about each other. They compiled the directory at the urging of a mediator, a staff member to help them during their separation.

But what happened next — an amicable separation that turned into an exhausting break, as the pair went from embarrassment to anger to finding a new balance — reversed Tolstoy's sense of the happy and unhappy families. firm opinion. Happiness is unique, inexpressible, a state that exists outside the narrative. And pain is what makes you like everyone else.

This is of course the view of divorce lawyers who will soon replace the hapless mediator. Nicole gets a role on the TV series, so she takes Henry to Los Angeles, where her sister (Merritt Weaver) and mother (Julie Hacketty) live. Charlie's insistence that the move was temporary -- "we are a New York family," he said to anyone who would listen to him -- became the focus of a dispute between the couple and their lawyer. The file was submitted. The volume is also raised. Henry - whose well-being is perhaps everyone's first consideration - is forced to go back and forth, and his life enters a state of dissonance.

Nicole and Charlie were creative collaborators, but now they're characters in the same drama that no one can control. "We need to tell your story," says Nicole's attorney, Nora (Laura Dern). Charlie visits two people—the plain-clothed gentleman (Alan Alda) and the suit-clad con man (Ray Liotta)—one of whom urges him to "change his narrative." For both parties, it means rewriting the past of a happy couple into a history full of struggles.

The most harrowing part of Marriage Story is the revisionist narrative. Many personal traits were rewritten as pathologies, and many mistakes were seen as potential crimes. The German social critic Theodore Adorno wrote: "Divorce - even among gentle, amiable, well-educated people - always creates a cloud of dust that touches itself. Everything that arrives casts a shadow and changes color.” Baumbach interprets this insight through vivid and precise imagery. He shows how the "realm of intimacy" (continuing to quote Adorno) is "transformed into a vicious poison when a state of prosperity collapses".

This intimacy didn't just simply disappear. Even at the height of their conflict - where they seem to have irrevocably crossed the fine line between love and hate - Nicole still calls Charlie "darling." There are still sweet residues left between them that offer some kind of hope, not necessarily a reconciliation, but also constraints that prevent the two from hurting each other continuously.

What happened was disastrous, absurd, and - as the lawyer put it - utterly mundane. Baumbach exploited and developed the outstanding talents of those actors, but he refused to use hyperbole. We can see farce spasms and melodramatic pains, but they are all present in the rhythm of everyday life. But that's not to say that Nicole and Charlie are confined to a stale and somber stagecraft -- an approach that's often seen as realism. They have distinct and complex personalities, and their professional and emotional lives fill their time and the screen, and we see anxiety, surprise, and occasional flashes of joy.

Baumbach tried to treat the two equally, and we saw his efforts. Like his other films, this one seems to be a very "personal" work, and maybe even more personal this time around. I am not simply describing its autobiographical nature. If you spend a few minutes googling, you can find information about his marriage, parents, in-laws and everything else you need to know. But if you've seen "The Squid and the Whale," "Margot at the Wedding," "When You're Young," and "The Meyerowitz Story," you've certainly been able to feel the message intuitively: of course he is Draw inspiration from your own life.

But you also can't expect the film to be completely objective and symmetrical. In some ways, "Marriage Story" treats Charlie more harshly than Nicole. This work underscores his selfish, self-pitying tendencies, but he also occupies the center of empathy throughout the film. "Marriage Story" seems to understand Charlie better, although Nicole has plenty of opportunities to explain herself. She seemed to be the one who made the breakup, her expectations and feelings had changed, and Charlie was trying to understand that. He was unaware of the consequences of some of his actions, including cheating Nicole with members of the theater.

Acts of infidelity are seen as some kind of incidental content, but this does not accomplish convincing. While "Marriage Story" delves into the intricate emotional jungle of the two, it takes a more coy -- and possibly astute -- approach to their sex life, whether the two are separated or together. Neither method has changed. Nicole has a moment of lust (but then it turns into a moment of anger), and Charlie - erotically speaking - is like a closed book.

The film's complex perspective—what Baumbach reveals and hides, and the way he follows these characters, even when they feel like they're in a state of stagnation, the situation is constantly changing—has a lot to do with Adam De River and Scarlett Johansson made tough demands. But in short, their performance can be described as extraordinary. They match each other so perfectly, or they create a mismatch in an interesting way that builds the trajectory of the whole story. Each of them possesses a somewhat mysterious charisma, a cubist message in their faces, and irony in their voices. They had expected to be able to understand each other, why all this?

One of the morals of the story is that we've never really understood each other, but we're obligated to try, which is punitive and somehow oddly motivating. Lawyers go their own way, insisting on simple answers to complex questions. Now is the time to point out that Alda, Lyotta, and Dunn are all almost quietly "sneaking" in this film, in part because the elements they perform in those roles are completely different from those of Charlie and Nicole. .

We sometimes see the two working together, but they are rarely on stage at the same time. With two significant exceptions, those dramatic moments employ borrowed discourse and conscious artificiality, conveying a strong, unadorned feel. Both scenes use a song from Stephen Sondheim's "Guys" - "You Can Drive a Guy Crazy," a jolly grumble about a charismatic narcissist. The process of dumping; and another song called "Alive" tells about the inner activities of becoming such a person. Driver's singing toward the end of "Marriage Story," an ode to need, takes us further, painfully, to the realization that "a person is a person, and that doesn't mean living."

It's a bleak conclusion that this delicate and messy film both embraces and rejects. As Charlie and Nicole move between two sprawling, self-righteous American cities, they find others both unbearable and indispensable: children, co-workers, in-laws, exes, and even the official sworn in in matrimonial court. To live is to live, it does not mean a person.

View more about Marriage Story reviews