First of all, I don't like this movie, the reason is in the short review. Film criticism can only be said to be based on the topic

I feel that the difference in the public image displayed by musicians is essentially a difference in the way people expect and imagine genius, and behind it is a change in the mechanism by which society creates and selects genius. Take Bach and Mozart as a comparison, the former's private life and creation are quite separated, and some commentators even say that it is impossible to imagine such an extraordinary work from the hands of a irascible father of fourteen children, as if he created cantatas and Masses, He is a completely separate person from dealing with school affairs, asking for a budget from the city council, and dealing with a family, and we cannot convincingly deduce the image of the former from the latter. Here in Bach, the musician hides behind his work, even saying that the musician is just a tool to carry and convey eternal ideas. Mozart's music has always been connected with his personal image, his various incredible achievements in his childhood, his wild and uninhibited personality charm, dealing with nobles and bishops without losing dignity, and even the various peach colors of the female images around him. News, such vivid stories undoubtedly add a legendary color to his music, and it is also the background that we cannot leave behind in the process of appreciating his works. Here, the composer's extraordinary charisma and the delicacy and perfection of music are two sides of the same coin, from which we can even see the shadow of pop superstars in the cultural industry of later generations. Since his time, all the musicians who have a number of musicians have to show the charisma of "allusions", such as Beethoven's early deafness, Chopin's patriotism, Tchaikovsky's homosexual rumors, all belong to this kind of halo, not only decoration The characters also add color to the work. Looking back from Mozart, Haydn's image is relatively simple, and Bach is even more lackluster. My explanation for this is that, from Bach to classicism (the Baroque period as a genre is not involved here, the reasons will be discussed later), it is not only an update and iteration of musical style, but the more important significance of this change is that it is different from the previous one. The divide between the modern and modern eras overlaps.

Perhaps Bach is best known for his few works as a court musician, but the real peak of his creation, whether judged by sheer occupation of energy or by spiritual depth and breadth, is his religious music. Especially religious musical compositions required for Lutheran religious ceremonies. His cantatas, passions, hymns, and scriptures belong to the great tradition of Protestant Lutheranism. As Liu Xiaofeng emphasized in his "Introduction to Social Theory of Modernity", Protestantism itself is divided into early and late periods. Whether narrated in traditional history textbooks or analyzed by Weber, Scheler, and others, Protestantism has always been in the face of the spiritual driving force that promoted the development of capitalism, and heralded a series of subsequent "victory of modernity." However, the divisive and complex movement of the Reformation has always been a point of contention. Just as Luther, the founder of this movement, has a very different image in the eyes of dissenters, we should view the Reformation, an extremely complex social movement, separately. To talk about Protestantism as a dynamic factor in the development of capitalism, it is reasonable to add the qualifiers of late Protestantism. The main purpose of early Protestantism has always been to save and purify the Christian faith from the vulgarity of the time. Luther himself is also known as the last fairy flower bloomed by the spirit of the Middle Ages. The question of the relationship between early Protestantism and late Protestantism is ignored here. The point is that Bach spiritually continued the Lutheran and Lutheran traditions, the piety traditions of early Protestantism, which made the transition from his musical style to the classical period to symbolize the ultimate transition from the pre-modern to the modern period in music. . The division here really starts from the conceptual system represented by music, and if the basis of this theory is further extended, the group of late Baroque composers other than Bach, such as Handel, Lully and the like, are more similar to Mozart in their image. The representative groups of modern musicians overlap (of course, if we consider that the Baroque movement was supported by the Catholic Church under the impact of Protestantism, but then swept across Europe, the picture before us will be more interesting). This is why we only talk about Bach and not the Baroque period in general.

In the pre-modern and modern times, the way of selecting musical talents and the expectations of musicians are completely different. It is even said that in the era of Bach, such musical talents were not needed. Bach's reputation comes from his decades of constant service to God, service to the princes, and the great tradition of the musical family carried by the surname "Bach". In his era, the structure of opportunity faced by musicians did not require charisma, and there was no room for such "charisma" to be tolerated. The musician's personality recedes behind the work, and we cannot deduce his radiant work from the image of a grumpy patriarch and member of the artisan class, and our appreciation for the latter does not require us to do so. In Mozart's era, the emergence of bourgeois audiences, the relatively independent opera house and the general commercialization of the music world gave them a space for their own possibilities in terms of career possibilities. The romantic trend of thought, which emerged as a rebellion against the spirit of enlightenment, brought this worship of the uniqueness of personality to a climax. Romanticism invented genius, and since then, expectations for a work overlapped with expectations for a composer, and people began to lose the acceptance of hard work day in and day out, believing that it could only be associated with mediocrity. What one expects is a really distinct character, dramatic life experience, precocious talent, and Charisma's charisma. Listening to music begins to require the private information of these composers as clues to interpretation. The demands for these elements were met by Mozart and the truly laudable composers after him, and it was this group of people who constituted a stark example of what Weber called a "cult of personality."

Interpreters who have grown up in this romantic atmosphere, whether they are music historians, critics, or audiences, are familiar with these expectations and norms, because they are social norms they take for granted. It is for this reason that we see how popular and hot the secondary adaptations and interpretations of these images are (think of the phenomenal musical "Rock Mozart"); it is also for this reason that the interpretation of Bach, especially in the Chinese context It is only in the middle of the world that it seems so unpredictable, and the image of Bach seems so pale in the modern judgment standard. Bach is not suitable for the dramatic adaptation of "The Biography of Mozart" (of course, it may be his great blessing), and there are almost only two stereotyped descriptions of him in the Chinese context: either praise how rigorous his works are, in line with Mathematical laws, or he sang the glory of God. In fact, the above evaluation is not wrong, but reduced to pale and superficial. However, it is this paleness that shows that the romantic genius theory in the context of modern society has no ability to absorb and explain the "Bach phenomenon". This further shows that Bach and other names appearing at the same time as him in the Canon of Canon are actually different in nature.

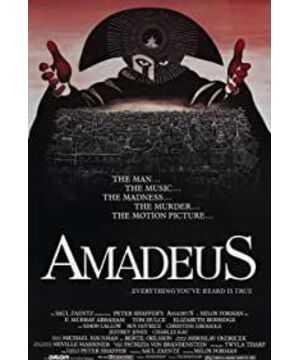

View more about Amadeus reviews