"Gaze" is not a one-way process, but a "dual experience".

summary of the story

Bedridden at home with a leg injury, photographer Jeffreys (James Stewart) enjoys peeking into the daily lives of residents across from his wheelchair with binoculars. The insurance company's old nurse and his girlfriend Lisa (Grace Kelly) take care of his day-to-day life while he is sick. Compared with Jeffreys, who is wandering and has an unstable income, Lisa is a lady of high society. She dresses up exquisitely and enjoys a luxurious life. In their relationship, Lisa is very enthusiastic and devoted, but Jeffreys is slightly alienated and indifferent. The reason he gave is: Lisa's life is far away from him, and Lisa is too perfect for him. Rather less attractive.

One day, when Jeffreys spy on the residential building opposite, he found that the salesman Lars' wife had been away for several days, and he himself acted strangely. He went out several times with his suitcase and wrapped the saw and knife in newspapers. Spying, Jeffreys suspected that the salesman killed and dismembered his wife, but there was no conclusive evidence. Regarding Jeffreys' speculation, Lisa initially held a negative and dismissive attitude, and the relationship between the two was not going well. Jeffreys was never able to ignite his love for Lisa.

After that, Lisa's attitude changed. She also became very curious about the suspected murder. She even went directly to the salesman's house in the opposite building to find the evidence, namely the salesman's wife's wedding ring. The salesman suddenly He went home and caught Lisa on the spot. In the process, Jeffreys, who was unable to move and could only watch by the side, was in a hurry. While he was worried about the safety of his girlfriend, Lisa also became the object of his peeping, and a strong attraction was born from this. . In the end, Jeffreys' police friend brought the murderer to justice. At the end, Lisa looked at the sleeping Jeffreys lovingly and thoughtfully, then put down the detective novel in her hand and picked up her favorite "Fashion". Bazaar magazine.

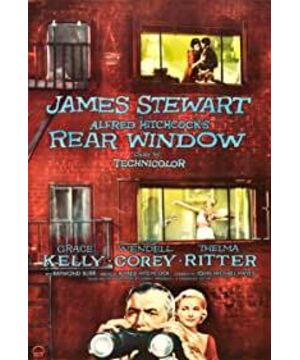

"Rear Window" - A Feast of "Gaze"

1. Double Gaze

"Seeing" can bring people the most direct experience and pleasure. The film called "Seventh Art" by Kanudu integrates audio-visual and transcends the limitations of time and space, and is one of the most important visual communication media for human beings. As a visual art film, to some extent, it is an intricate collection of symbols. Metz's second film semiotics theory holds that the audience is immersed in the film's symbols and narrative system during the viewing process, and generates narcissistic identification in the gaze of the screen, and this identification is achieved through the audience's perception of the film. The camera and the realization of identification with the characters of the film.

The movie "Rear Window" creates a "double stare". The subjective peeping perspective of the hero Jeffreys reveals a case of murdering his wife, while the audience in front of the screen is staring at "Jeffreys' stare". The staring tool of the hero is a telescope and a telephoto lens, while the audience's staring medium is the film image. Following the subjective perspective of the protagonist, the audience participates in the narrative of the film, generates strong curiosity, is aroused by the suspenseful color of the film, doubts and agrees with Jeffreys' "gazing achievement", and the film constructs a dual , Gaze mechanism that works from the inside out.

2. The reversal and confrontation of gaze power

The gaze in Rear Window is not limited to the unilateral power exerted by the audience, but also includes the gaze of the camera itself on the audience. Traditional films deliberately avoid having actors looking directly at the camera, which makes the audience aware of the presence of the camera and disrupts the immersive viewing experience. However, with the innovation of film language, actors looking directly at the camera began to be fully utilized, the "fourth wall" was broken, and the audience was included in the presentation mechanism of the film. In addition to comedy films that are good at witty interactions with audiences, this deviant lens language has also become a common technique used in suspense thrillers.

The eyes looking directly into the camera create an atmosphere of dialogue between the characters in the film and the audience. The act of staring is often accompanied by the release of anxiety. When the audience is stared at by the characters in the film, people's panic and horror are also fully mobilized. Following Jeffreys' eyes, we have been watching the solution of this wife murder case, and until the end of the film, the murderer received a letter from the hero, he found that his crime had been exposed, and we were passing through Jeffreys. His telephoto lens was watching the murderer, and he suddenly looked at the camera with anger and wide eyes, and the audience's identity as a bystander was suddenly broken. The audience, who is always in the same staring position as the hero, becomes the "gazing party". Under the reversal of power, the audience has to "share" the horror of this moment with the exposed Jeffreys. People's psychological identification with the film's characters is also here. peaked in one shot.

The same trope appears at the end of Psycho (1960), when the schizophrenic murderer stares grimly at the camera with an eerie smile, and the film ends, leaving a staring shadow in the minds of the audience. The audience is included in the interaction between "gazing" and "being stared at", and has always been given the identity of the audience as the viewing object of the film. This is Hitchcock's allegory for the presentation of traditional Hollywood classic films, and it is a taboo-breaking event. provocative.

Next is the climax of the film, where Jeffreys' murderer is found sneaking into the peepers' house, the doorknob being slowly turned, the ghostly figure in the dark, for the murderer's coming, Jeffreys, who has limited mobility, is in addition to the extreme Terrified. The murderer, who has always been in the position of "being stared at", has the "right to stare" at this time. He approaches the hero and also the audience whose psychological panic has been mobilized to a climax, and the psychological identity is regenerated.

Facing the approach of the murderer, Jeffreys sat in a wheelchair and slid to the window, aiming the dazzling camera flash at the murderer to try his best to delay. This was the only resistance he could do, and the camera was his important peeping tool. , has become a weapon for him to protect his own personal safety. This self-defense counterattack is to some extent a confrontation and competition between the two men's "gazing power".

It is not only the murderer who is stimulated by the flash, but also the audience behind the camera lens. In this scene, the murderer and the male protagonist are in a state of staring at each other. Hitchcock adopts a method of concretizing the abstract visual feeling. The strong light appears like a flame, and the murderer is stimulated by the light. After that, I had to step back a little, and then the camera was aimed at Jeffreys, and turned to the subjective perspective of the murderer. The orange halo spread out with the dot as the center in the picture, just like we were stimulated by strong light in our daily life. At this time, the audience has a sensory identification with the murderer.

Women "stared"

The theory of film ideology holds that film, as the art of "seeing and being watched", hides the power mechanism of ideology behind it. The photographic machine is considered a symbol of power, and the symbols stacked in the film provide the viewer with a transcendental world. The viewer is drawn to think, mobilize emotions, and identify with the film. As a medium for exerting power, the camera is often used to express the interaction of power in human society.

"Gaze" is a viewing method that carries power operation, desire and identity awareness. The viewer is mostly the subject of "looking", but also the subject of power and desire. The audience is mostly the object of "being seen". It is also the object of power, the object of desire and desire. "Gaze" is a kind of power exerted by the viewing subject on the viewed party, which implies the relationship between the subject and the object, the suppression and the suppressed. It is a symbol of power and a producer of power at the same time.

In gender power relations, males dominate and females are usually subordinated to males. Under the vision of male desire, the women in the film become the "gaze" party. In the book "The Way of Seeing", John Berger proposed that the "ideal" viewer in the way people see is usually a man, and the image of a woman is used to please men. In classic film narratives, female characters often carry and create trouble, and the ultimate resolution of the conflict needs to be rescued by men. Feminist film theorists believe that the castration anxiety of men and their female imaginings contributed to this classic gender narrative mode.

1. The "male gaze" - the catalyst for love

The murder case surfaced through the male protagonist's sensitive subjective vision, and was thoroughly solved in his gaze and speculation. The protagonist of the narrative is not so much the suspenseful case as it is the "male gaze" of Jeffreys and his A display of male intelligence and power. Unlike most of Hitchcock's suspenseful thrillers, "Rear Window" is somewhat of a "dual-line" film that focuses on the "male gaze" and its power. Hitchcock once said in a conversation with Truffaut that if the suspense revolves around the question of "is he an Avenger" and it turns out to be true, such a setting lacks drama, and he is usually happy to be suspected. is not the direction of the murderer.

Indeed, audiences of suspense films often have psychological presuppositions like "it's not that simple". If only from the murder case in the film itself, this is the only story in which the doubts were successfully confirmed and a happy reunion occurred. Hitchcock, however, pared down the usual quirky twists of the suspenseful plot by dividing the focus of the dramatic conflict to another of the film's less obvious main threads: love.

The professional setting of the male protagonist already hints at his identity as a "gazinger"—a photographer, and the telephoto lens of the camera is his best medium for peeping, and the "violent machine" that imposes his right of viewing. As a photographer who needs to capture images by moving, Jeffreys' injured leg confines him to a wheelchair and indoors. He temporarily loses the power to use photography to stare, and is in the "castration anxiety" of men.

Jeffreys narrowed the photographer's broad field of vision to the living beings in the opposite residential building. Couples sleeping in the sun on their balconies, fitness women with extensive communication, and lonely women rehearsing their dating scenes in advance were sent from upstairs in bamboo baskets. The puppies to the ground, these are the objects of his gaze. When Jeffreys peeps, the camera lens merges with the telescope's perspective, and the movement of the lens reflects Jeffreys' subjective perspective.

However, the gaze time assigned to each scene is different. The woman who loves fitness occupies the longest lens gaze. The male protagonist behind the binoculars is very interested in this woman, and he hesitates to look away from him. In his eyes, you can see the satisfaction of desire being satisfied. While Lisa, his girlfriend standing next to him, was gorgeously dressed, caring and intimate, Jeffreys was always indifferent and alienated.

At first, Lisa, who frequently appears by the hero's side, is on the same side of the peeping medium as him, and she cannot be his object of peeping. We learn that Lisa's is a high-class lady who loves fashion and enjoys a luxurious life, while Jeffreys considers himself a wandering photographer, not in the same world as Lisa, "she's just too perfect" , he explained to the insurance company nurse. In the face of Lisa, whose social status is higher than him, and his short-term physical defects, the male protagonist has the "castration anxiety" of male power. He seems to be unable and unable to act on Lisa with the desire to stare, lacking the power of staring The blessing of this kind of love seems to be dispensable to the male protagonist.

At this time, Lisa has not yet discovered the crux of the relationship. She does not understand that Jeffreys is trying to solve a murder case by peeping, and often interrupts her boyfriend's prying. Then, Lisa suddenly became curious and voyeuristic about the case, and even went directly to the salesman's house to find evidence - the wedding ring of the murdered wife. At this time, Lisa came into the peeping field of view of the hero. He watched the whole process of Lisa climbing the ladder and sneaking into the suspect's house. At the same time, he was worried about the safety of his girlfriend. At this time, the audience's perspective and Jeffreys were once again integrated. , we empathize with the male protagonist's worries and anxieties.

Lisa was caught by the murderer and then successfully escaped. The male protagonist changed from anxious to calm, immersed in the gaze of his girlfriend, and observing his micro-expressions can see the emergence of desire and the pleasure of being satisfied. When Lisa finally came to the other side of the peeping, Jeffreys's eyes were fixed on Lisa, and Lisa, who put down her body and actively cooperated with solving the case, stepped down from the "altar" and became a desirable object. The feelings of the hero and heroine finally reached the peak of resonance. It has to be said that the realization of the "male gaze" is the catalyst for the love between the two, and behind it is the powerful force of subjective vision at work.

2. Women's self-construction under the male gaze

The "male gaze" is by no means accompanied by direct visual stimuli, but behind it is a powerful patriarchal metaphor. "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Film" considers "gender differences" into the form and narrative of the film. Under the background of traditional patriarchy and phallus centrism, women are usually castrated into the symbol system. They always need men to fill the gaps in their identity. They are shaped and actively shaped themselves into "objects" viewed by men, castrated and good at self-castration. In the narrative of traditional mainstream movies, the subjective perspective of men often dominates the development of the plot and leads the audience's vision, while women always take the initiative to incorporate themselves into the androcentric system.

Lacan's Mirror Theory believes that "gazing" is not a one-way process, but a "dual experience". When people are gazing, they will also stare at themselves in the opposite direction, and strive to achieve self-affirmation. When Lisa was also deeply attracted by the suspected homicide in the opposite building, she seemed to discover the power of the attractiveness of the person being stared at in the process of gazing. Perhaps it was this that inspired her to take the initiative to walk into Jeffreys. In the telephoto lens of , get the love generated by her boyfriend under the satisfaction of peeping pleasure by being stared at.

In other words, the realization of the power of gaze is not the result of a single application. The person being gazed will identify and construct himself according to the image in his eyes, and the idealized image comes from the eyes of the gazer (male). The product of male power is the embodiment of women being always subordinate to men in films, which is also an important reason why Hitchcock's films are criticized by feminists.

In the film, the completion of female identity and construction is inseparable from the dominance of male vision, which to some extent reflects the power anxiety of the male-dominated society. Jeffreys keenly discovered the pathological changes in the salesman’s marriage and paid great attention to it. The intense curiosity aroused by voyeurism also implies the male protagonist's anxiety about the marriage between the two sexes and the difficulty in taming Lisa into a traditional female image.

So whether it's for the purpose of saving love, or really driven by curiosity, Lisa's transformation and pandering is somehow a triumph of the "male gaze". When Lisa put aside her opinions and participated in her boyfriend's staring activities, and took the initiative to put herself in the position of being stared at, she finally succeeded in capturing Jeffreys' heart. At the end, Lisa changed out of her fancy clothes. She was wearing simple clothes and looked at Jeffreys who was sleeping. The expression on her face seemed to be thoughtful and a little satisfied. She put down the detective novel in her hand and picked it up. She has published Harper's Bazaar, which she really likes, so I'm more inclined to think that Lisa's transformation is a conscious catering. When the dominant and subordinate relationship between the two of them "staring" and "being stared at" is determined, the emotional contradiction between the two is resolved. It's hard to say, however, that this happy ending didn't come at the expense of women's compromises.

In Hitchcock's films, women are often portrayed as guilty, weak, or trouble-making "beautiful women", and women who "deviate" due to personal desires are often punished. Janet Lee, who has selfish desires and refused to be identified by the male protagonist; Ingrid Bergman, who fell into the abyss to atone for her spy father in "Beauty's Plan"; almost surpasses men in "Butterfly Dream". Rebecca, who died of cancer but died of cancer; Tibby Headley, who took the initiative to promote love but was pecked all over in "Birds"... Compared with these suffering "blondes", Grace Kelly seems much luckier.

The power of the "male gaze" is also exemplified in Hitchcock's other film, Vertigo (1958). Vertigo tells the story of John, a resigned police officer suffering from acrophobia, who is entrusted by a friend to stalk his delirious wife Madeleine. Amid the stalking and peeping, the male protagonist is hopelessly in love with this mysterious and vulnerable man. woman.

During this process, the camera always follows the subjective vision of the hero, but all this is a clever game set up by his friend to kill his wife. The woman the male protagonist falls in love with is deliberately played by Judy who has the same face as his friend's wife. However, Judy, who was stared at and played the other, fell in love with John. She tried hard to make John fall in love with her real self, but under the strong oppression of male power, she went to the sinking and loss of herself. Manipulated and manipulated, Judy eventually dies in a panic.

In Vertigo, in addition to the intricate suspenseful narrative, the second half of the film focuses on how men use visual power to push a woman in love into the abyss. The role of Judy is a victim of a typical patriarchal vision. At first, Judy's manipulator was John's friend. He made Judy imitate his wife from dress to behavior to confuse the male protagonist. Then, in order to get John's love and become the perfect mirror in John's eyes, she compromised step by step And giving up herself, this compromise is also presented visually - she replaced the heavy makeup and hair, and completely transformed herself into the Madeleine in the vision of John's desire. However, the necklace she got for playing the other still exposed her. The necklace in the film is a metaphor of self-lost. In the end, it is not only the body that falls from the high-rise building, but also the women who are engulfed by the "male gaze" who independently construct their own identity. possibility.

references

[1] Zhao Bin. "Introduction to Art" [M]. Beijing: China Film Publishing House, October 2016 edition, p. 306.

[2] Zhu Xiaolan. "The Theoretical Research on "Gaze" [D]. Nanjing: Nanjing University, 2011.

[3] John Berg. "The Way of Seeing" [M]. Guangxi: Guangxi Normal University Press, May 2015, p. 91.

[4] Francois Truffaut. "The Dialogue between Hitchcock and Truffaut" [M]. Shanghai: Shanghai People's Publishing House, January 2007, p. 36.

[5] Yang Yuanying. "Film Theory Reader" [M]. Beijing: Beijing United Publishing Group, February 2017, p. 527.

[6] Zhong Yuanbo. Gaze: Watching as Power [J]. Art Observation, 2010 (06): 114.

2021.10

View more about Rear Window reviews