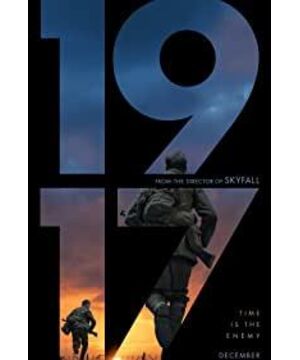

. This film starts with war and ends with nothingness, breaking many people's arrogance and prejudice against war and death.

1. The experience of war starting from images

Leaving aside some of the film technology that fans love to talk about, my first withdrawal from the film started when the corporal inadvertently pressed his wounded hand into the abdominal cavity of a dead body. As a half medical student, I instinctively raised my hand, and after finding that there was no problem, I subconsciously recalled terms such as "bleeding wounds, debridement with clean water, bacteria in carrion, gauze isolation effect" and so on. Come to the conclusion that this soldier may have died of a wound infection if he was not treated in time. —— This is the immersive experience that the imaging technology of this film brings to me. If it weren't for "one shot to the end", I might just expect a medic to save him in the follow-up plot.

The above situations seem to be just two different viewing experiences, and they are even somewhat unremarkable. But for a movie fan, the former is a state of being unattainable. That is, at that moment, I'm a bystander standing next to the character, not a moviegoer sitting on the couch, eating a snack. And, at that moment, my viewing rhythm was almost completely synchronized with the director's narrative rhythm - "I" was thinking about the current soldier's response, rather than helping the director design the subsequent plot direction. This kind of experience, in other types of movies, is an effect that is difficult to achieve.

It was also from this moment that I stood one meter away from the corporal and went through the difficulties of the war with him.

From then on, we began to walk with the corporals, stepping on the mud of the trenches mixed with carrion and blood, hunched over, and quietly on the road. Smell the stench of dead horses and dead people, listen to the roar of bombs and mines, and crawl forward. In panic, we watched the corporal beside us accidentally stuffing his injured hand into the corpse, and we felt a little nauseated in our hearts. Watching the 16-year-old young child die next to him, while the soldiers on the side slapstick and sing playful songs. Later, together, we gave the "stolen" milk to a young girl who was holding a baby girl, even though there were ruins burning in the raging fire, a hellish ruin.

Many times, when we watch movies, we always carry a kind of God-like arrogance and scrutiny from a third party. We always put the characters and plots in the film into a box and observe frame by frame with a magnifying glass, while ignoring the fact that the story in the film may be real, the bones and blood of the model characters and plots. We habitually reflect on the connotations and metaphors expressed by movie stories, reflect on the social and historical background of the stories, but do not consider whether we have stood outside the stories at this time, but have not entered into the stories. Perhaps, one of the purposes of the director's insistence on using "one shot to the end" and a large number of face shots is to let the audience temporarily put aside this habitual reflection and return to the story itself. He is trying to guide the audience not to recall the depression brought about by the war in the early 19th century, but to feel the cold and smoothness of the mud mixed with mud and blood in the trenches of the winter battlefield.

2. The impression of death should not be filled with nothingness

Audience stereotypes about war, often "anti-war," "anti-human," "piles of corpses," and "debates of justice and injustice." But when discussing these archetypes, they often get caught up in a show of nothingness—a show of form without substance. They talk about anti-war, but most people don't want to experience the bloody deaths on the battlefield, and are obsessed with analyzing the logic behind history and numbers. They discuss justice and injustice, but they do not understand the confusion of ordinary people in the shadow of their survival in the war, and they are immersed in overwhelming thoughts and political fantasies.

They are the ones who are bound. The topics they discuss are extremely meaningful, but they themselves are nothing and hide behind the topic. Like the fear of loneliness, they fear meaninglessness.

"1917", in my opinion, is precious because it gives the audience an experience closer to the scene of the war. It inherits the stereotype of war movies expressing anti-war themes, but breaks the grand narrative of heroes and history in war movies. It rejects the comparative analysis of big society and little people, focusing instead on a specific person - Corporal's war experience and his "observable" behavior and emotions. Such narratives were rare before, and there will not be many after that. (In existential parlance, it's a "here and now" experience that goes beyond being there.)

Finally, a superfluous opening remarks written for Mr. Corporal are attached.

"I am a young man in his early twenties. A year ago, I came to this battlefield because I couldn't stand the cynicism of my relatives and female friends, and had to be separated from my young wife and young children. For the sake of being a hero, that doesn't make sense. I'm just tired of people who say I'm cowardly, uncouth and unpatriotic, and pointing the finger at my family behind my back.

Within a few months, I got a medal, a little tin thing. I traded it for a bottle of wine, well, at least the wine made me less restless.

This morning, I was looking at pictures of my family when I was suddenly called by the officer. He asked me and my brother to go to another position to deliver a letter. oh, shit. Two people, crossing several positions in a row, you just call me dead. When my brother goes there, at least he can save his own brother, and at least he can understand the map and at least not get lost. What can I do? I don't know how to read maps, so I don't know how to get there. what can i do? Help him stop the gun? holly, shit! Don't tell me they're going to give me medals, it's said that hundreds of thousands of that stuff have been sent out, and maybe even a bottle of wine won't be exchanged in a few years. "

View more about 1917 reviews