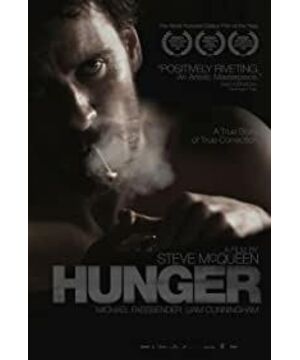

"Hunger" may be the most powerful movie this year. It uses a quiet pace to show fierce struggle, a 17-minute bold long shot, and that amazing integration. Steve as a video artist McQueen showed his talent beautifully. If you have missed "Day Night Day Night", then you must not miss "Hunger"! Incidentally, Steve McQueen once said that he was influenced by the New Wave and Andy Warhol films.

S&S: Why would you want to tell such a story about Bobby Sands and the Irish Republican Army's hunger strike?

SM: This incident happened in 1981. It had a great impact on me when I was 11 years old. It was a turning point in my life. From then on, when I looked out of the window, the world was no longer what it looked like, and I started to see some cracks. The hunger strike is a kind of thought and an ideal; and people will live or die because of it. I am very interested in this level of passion and belief.

S&S: What is included in your research survey?

SM: My investigative work started five years ago, and the first thing is to read. I already have thoughts and memories about this matter in my mind. The more I study, the more fascinating I find it. When we first went to Belfast, we met a lot of people, including relatives of Sands, and they were very generous, whether they were the royalists or the Republicans, but at the same time you could feel an undercurrent of idealism. The last thing I can't get rid of is the people there. They may be my mother, my father, and my sisters. They are not foreigners or outsiders.

S&S: How did your co-writer and playwright Enda Walsh join?

SM: Sometimes it’s good to brainstorm with others. I know I want to work with an Irish writer, so we also interviewed a few. Many people are scared of this subject, but Enda is different. He is rather weird. . I didn't even read the script before making this film, and before Enda joined, I wanted to silence the film completely without a single line.

S&S: What kind of briefing did you give to Enda Walsh?

SM: What I said to Enda is that I hope the beginning of the film will be like a stream, allowing you to swim along with the water and feel the environment where you are. Then suddenly there was a torrent that disrupted and interrupted your reality. In the third part is a waterfall, a feeling of losing gravity, falling straight down. This is how I feel about this film.

S&S: How did the script develop under this premise?

SM: We spent an intense and heavy week in Ireland talking with prison officers, and then Enda wrote the first draft. The next step is like chiseling marble. You know what you don't want, but you still need something; it doesn't matter if it's just a piece of rubbish on the table, to go through it. Then I thought of the funny walking in Monty Python (Annotation 1), and then it reminded me of "routine". Only then did I realize that this whole thing is actually about a habit and convention. As if at the beginning, the prison officer left his house, how ordinary it looked. The routines in "Hunger" are more severe and absurd than those in Hou Xiaoxian's movies, for example, because "Hunger" has a lot of violence, and these violence are routines.

S&S: After visiting the Maze prison where the hunger strike took place, have your thoughts been affected in any way?

SM: Although they won’t let us shoot there, it’s great, because the prison system will standardize your camera; the system will bring you the system. In fact, narrative films sometimes feel simpler, because you already have a template and the form is there. The next step is to see how you change or destroy the form. Disrupting the form will make it more interesting. And what I'm trying to do is in the field of art. This is different. You have to create new languages and new forms.

S&S: Have you never worked with an actor before?

SM: I used to work with actors from the Amsterdam Film School, and that experience was really helpful. It made me discover that I like actors. All you need to do is take the same risks as the actors. I would say, "Look, I took all risks here." When they know this, they will want to keep pace with you, and even try to surpass you. I try to get them lost, like silly ascetics; they do this in order to get closer to God. Sometimes you have to get rid of the shackles. This is what I want them to do so that they can be closer to reality.

S&S: There is a scene between Sands and the priest. This scene lasts for nearly twenty minutes, mostly from the side with a fixed camera; is this very risky?

SM: I don't agree. The people around me were scared, and so was the producer. They said we need some front and back shots. Do you know, that's why those people make so many bad films, and all they should do is give it a go. In the middle of the shooting, I once said, "Do you know? I feel so boring. We have already taken the shot. Let's go." Because we are all arguing, fighting against Channel 4 or something. At the end of the day, we finished work and went home at 4:30 in the morning. It was fucking great, we got it, and then I knew we got it.

S&S: Was this scene filmed just once?

SM: We took four shots in total and used two rolls of 20-minute film. For me, this scene is better than Rod Steiger and Marlon Brando (Annotation 3), because this is life at a critical juncture; life or death. The scene was not improvised, it was all written in the script, but the words seemed to come out of their mouths, like a jazz. The atmosphere in this scene is very tense, but as an actor, where are you going to find such a situation where you can say "ultimate"?

S&S: Why would you want to shoot in Belfast?

SM: What happens after the camera is as important as what happens before the camera, because all those who are behind the camera are more or less related to these events. There is a power from memory and a taste of the past floating in the present. An actor's mother had brought things into Maze Prison, another actor's father had been imprisoned there, and an uncle was the prison officer inside. Everyone has something in this story, which feels great on the scene.

S&S: Surprisingly, there are many different points of view in the film.

SM: I see myself as a prison officer, and I see myself as a fighting person. If you think from the perspective of others, it is obvious that each of them is a flesh and blood person. What's worse is that the whole background is not the person itself; you just have to do what you have to do. We are all human beings. Every day we do something wrong. We are not innocent. You and I are all part of this game.

S&S: You give the audience a lot of space to enter this film.

SM: The video can tell a lot, it's impossible to cover everything. What you have to do is to open up people’s imagination or something in their hearts to complete a film, and I don’t know what that thing is.

S&S: When and how did you come into contact with movies?

SM: When I was at Goldsmith University, I had a Swiss girlfriend. She liked movies and took me to see a lot of movies. Before that, I hadn’t been to movies at all, because in the place where I grew up, people would think you were watching them alone. Movies are playing cool and making fun of you. The late 1980s and early 1990s were a wonderful time. At that time, we had great places, such as Riverside and Scala Theater, where I learned my movies. There I saw how people in France, Italy, and Taiwan fell in love, and how Romanians eat breakfast. This is really surprising, because the things that can be learned are so rich.

S&S: Why did you wait until now to make your first feature film?

SM: I wanted to make the first film when I was 23, but I had to wait 15 years first. When I left art school, I didn't know where I could film, I couldn't shoot in the UK, so I applied to New York University, but I only stayed for three and a half months, and I hated it so I came back. I didn't have any expectations for the way they made the film. They wouldn't let me throw the camera in the air and pick it up again because it was unconventional.

S&S: Since you had this idea five years ago, this film has further political resonance.

SM: The strange thing is that stories like this are happening constantly, both in the past and in the present. Many people who watch this film think that this kind of thing happened in a very far away country, but they don't know that it actually happened in their backyard. This is a story of being swept under the carpet. Twenty-seven years have passed. Someone should lift the carpet up and let everyone see what happened.

S&S: Will you make other movies?

SM: I don't have any ideas yet. I am not in a hurry. Others gave me a lot of scripts, and watching these scripts feels like a blind date. If I shoot the next one; it's like being in love, you don't know when and how it will happen.

Annotation 1: The famous British comedy performance group produced and broadcasted the Four Seasons TV series from 1969 to 1974. In 1975, it launched the film history classic "Monty Python and the Holy Grail", which influenced many later comedy works. The well-known director Terry Gilliam Was also one of them.

Annotation 2: Channel 4 of the UK's influential public television station is the funder of this film.

Annotation 3: This should refer to the rivalry between the two in "On the Waterfront".

View more about Hunger reviews