George D. Demet

Originally published on DFX, July 1999

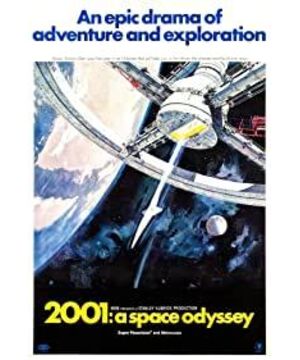

Stanley Kubrick's film 2001: A Space Odyssey, more than 30 years after its premiere, still inspires audiences. Like a work of art or a classical symphony, its appeal increases over time. It was a very unique film that conquered that generation of young people in the late 1960s. They embraced the film's visual message with religious passion. Although initially heavily criticized by major film critics, the film is now widely regarded as one of the greatest masterpieces in film history.

This epic film that spans time and space begins four million years ago in the prehistoric African savannah. At that time, the distant ancestors of mankind had to learn to use tools to survive. Then, the movie scene cuts into the sci-fi scene of the early 21st century. At that time, human beings had realized life in outer space, and the first manned space mission to Jupiter was about to be carried out. The crew consisted of two human astronauts and a super-intelligent computer called HAL. The final part of the film features a 23-minute film with fantastic light and shadow effects, and a mysterious ending that's enough to make viewers question themselves and the world around them.

Director Stanley Kubrick, in addition to this film, is also known for directing films such as Doctor Strange, A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon. He began collaborating with science fiction novelist C. Clarke in early 1964, with the aim of producing "a well-recognized science fiction film". They spent a year writing the plot, and in mid-1965 Kubrick began early production on the film.

At Clark's recommendation, Kubrick hired space shuttle consultants Frederick Ordway and Harry Lange, who had assisted National Aeronautics and Astronautics, as the film's technical advisors The agency and some of the major contractors in the aerospace industry develop advanced spacecraft concepts. Ordway persuaded dozens of aerospace giants, including IBM, Honeywell, Boeing, General Dynamics, Grumman, Bell Telephone and General Electric, to participate in the production of the film. He convinced these companies that it would give them good publicity. Many companies provide extensive documentation and hardware prototypes for free in exchange for "product placement" in the film. They believed the film would be a big-screen advertisement for space technology, and were more than willing to help Kubrick's production team in any way possible. Lange is responsible for designing a lot of the hardware you see in the film.

Every detail of the production design, down to the most insignificant element, is designed with a strict pursuit of technical and scientific accuracy. NASA Apollo senior director George Mueller and astronaut Deke Slayton are said to have dubbed the Burnhamwood UK shooting base after seeing all the hardware and documentation around the studio. For "East NASA". Even today, most viewers and critics still find the props and spaceships used in this film more convincing than many recent sci-fi films. While most early sci-fi films only wanted to achieve a simple "future" vision, the design and production aspects of this film tried to be as technically plausible as possible.

Production designer Anthony Masters was responsible for realizing Harry Lange's design concept. He accomplished this task with the assistance of more than a hundred model makers and other members of the art team. To increase the authenticity of the film, the production of many props, such as the spacesuits and dashboards, was outsourced to various aerospace and engineering companies. All props and models must be approved by Kubrick for use in the film.

Kubrick's relentless pursuit of perfection was most evident in the design of the mysterious alien monolith (the Black Stone). The original idea of the Black Stone was a tetrahedron, but none of the models were shocking enough. Later, Kubrick commissioned a British company to manufacture a three-ton block of transparent fluorite. However, it also doesn't have enough visual punch. The final black stele is made of wood and sanded with graphite to obtain a completely smooth surface.

It's not uncommon for the film crew to go all out to make a unique scene for a movie. The movie's most impressive scene is the interior of the spaceship Discovery. To cope with the weightlessness of the space environment, the spacecraft's crew compartment was designed as a centrifuge, simulating gravity through the centrifugal force generated by its rotation. British aircraft company Vickers-Armstrong Engineering Group built a 30-ton rotating "Ferris wheel" that cost $750,000 to make. The unit is 38 feet in diameter and 10 feet wide. It can spin at up to three miles per hour and comes with the requisite chair, desk and console. All these parts are firmly attached to its inner surface. Actors can stand at the bottom and walk around while the scene revolves around them. The operator of the camera sat on a gimbal seat, and Kubrick used early video feeds to indicate movements in the control room.

Kubrick himself oversaw the film's special effects team, which included Con Pederson, Wally Veevers and Douglas Trumbull. Douglas also created special effects for other sci-fi films such as Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Blade Runner. Work on the film's more than 200 special effects scenes began long before Kubrick and Clark had finalized the screenplay. Kubrick used a series of experimental effects shot in an abandoned New York corset factory to help "sell" the film to studio executives. Kubrick's production team wanted to set a new quality standard for film visuals. As Kubrick said, "I felt compelled to make the film in such a way that every special effect that came out was completely convincing. This has never been done before in the history of cinema."

The film was one of the first to make extensive use of frontal projection. This technique is to project the background from the picture through a reflective surface. The prehistoric African scenes were actually shot indoors at the Burnhamwood location in the UK. Pictures from the second unit were projected onto a screen 40 feet long and 90 feet wide behind the actors, giving the illusion of an outdoor scene. Frontal projection is also used in some of the outer space scenes of the film. The more traditional rear projection technology is only used on the many video monitors and computer screens that appear in the film.

While most of the visual effects techniques in the film had been used before, there was a series of shots that opened up new technical and artistic foundations. "Stargate" in the final part of the movie, some swirling lights and shadows fly around the astonished theater audience. This was created by a "slit scan" machine developed by Douglas Trumbull. The machine shoots along two seemingly infinite planes, creating other effects of the sequence by applying different colour filters to the aerial scene segments, as well as photographing some interacting chemicals.

Through creative cinematography, hard work and dedication, the crew also achieved several other special effects. To allow a pen to "float" in a weightless environment, the crew attached it to a rotating glass disk. The illusion of astronauts floating in space is created by hanging stunt performers upside down from wires from the studio ceiling, often for hours at a time.

The special effects of this film are all done without the help of computer technology, which is remarkable. Kubrick held his crew to the highest standards to ensure the film looked as realistic as possible. In order to ensure that the elements of each special effect scene were as crisp and clear as the direct image, he refused to use some techniques that would have made the scene faster and cheaper. Of the film's $10.5 million budget, $6.5 million was spent on special effects alone. And nearly two years after major cinematography ended, the film was finally finished.

When the film premiered in the spring of 1968, many viewers were confused. The film has no traditional plot structure, little dialogue, and an ending that left many bewildered. Some leading film critics, such as Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael, were strongly critical of the film, arguing that Kubrick sacrificed the film's plot and themes for visual effects and technology . However, younger audiences quickly discovered the film, making it a huge commercial success. The glowing reviews of many young critics have led many of its original critics to re-evaluate it, and some have even retracted their earlier reviews. A large number of articles and books have appeared on the film, with different interpretations of the message the film is meant to convey. Many agreed with Stanley Kubrick that the film, as a visual masterpiece, is a very subjective work that cannot be explained objectively. It's like one cannot "explain" Beethoven's Ninth Symphony or Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa. The film has inspired many people who say they later became filmmakers, engineers or scientists because of seeing the film.

Even today, the film still appears in people's lives. Film and television commercials deliberately reference its imagery, countless fans post their thoughts on the internet, and articles like this continue to appear. It's a testament to the genius and dedication that Kubrick and his team possessed, and the future they've so carefully built remains convincing to this day.

Many thanks to the following sources for preparing this article:

Ajer Jerome, editor. The Story of Making Kubrick 2001. New York: New American Library, 1970.

Bizzoni Pierce. 2001: Shooting the Future. London: Aurum Press, 1994.

Letterman, Herb. The Movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. American Cinematographer, Vol. 49, No. 6.

View more about 2001: A Space Odyssey reviews