light translation

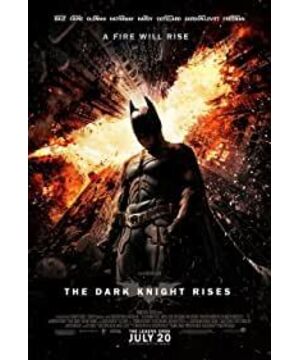

of The Dark Knight Rises proves once again how Hollywood blockbusters are an accurate indicator of the ideological impasse in our society. Here is the (brief) plot. Eight years after The Dark Knight, the previous episode of the Batman saga, law and order rule Gotham: Extraordinary powers conferred through Operation Dent, Sheriff Gordon Violent and organized crime has been virtually eradicated. But he somehow feels guilty for covering up prosecutor Harvey Dent ("The Two Faces") (who stumbles and dies when Dent tries to kill Gordon's son before Batman rescues him, Batman With this fall, Dent's myth was fulfilled, and he allowed himself to be demonized as Gotham's villain), and he planned to admit his conspiracy at a public event honoring Dent, but he felt that Gotham was reluctant to admit his conspiracy. Hear the truth. Bruce Wayne is no longer active as Batman, he lives alone on his estate while his company is on the brink of bankruptcy after he invests in a clean energy plan aimed at using nuclear fusion, because when Wayne learns of the reactor After it could be transformed into a nuclear weapon, he stopped the program. The beautiful Miranda Tate, a member of the Wayne Enterprises Executive Committee, encouraged Wayne to reintegrate into society and continue his philanthropic work.

That's when the movie's (number one) villain comes along: Poison, a terrorist leader who was once a member of the Shadow League, gets a tape of Gordon speaking. When Poison's financial shenanigans bring Wayne's company to the brink of bankruptcy, Wayne entrusts Miranda to run the business and falls into a short-lived romance with her. (Here, Miranda is up against Selena Keller [Catwoman], a snitch who eventually rejoins Wayne and the policing force.) When Wayne learns of Poison's mobilization, He returns as Batman and confronts Poison, who tells Wayne that he took over the Shadow League after the death of Ninja Russ. The poison wounded Batman in melee combat, throwing him into a prison from which escape was virtually impossible: fellow inmates told Wayne that the only one who managed to escape from prison was a Willpower-driven child of last resort. Poison also managed to turn Gotham into an isolated city-state while Wayne in prison recovered from his injuries and retrained himself to be Batman. He first lured the vast majority of Gotham's police force underground and ambushed them; then he detonated most of the bridges connecting Gotham to the mainland, declaring that any attempt to escape the city would detonate Wayne's fusion reactor , that reactor has been taken over by poison and transformed into a bomb.

Here we arrive at a pivotal moment in the film: the takeover of the poison comes with a massive political-ideological offense. Poison exposes the lies about Dent's death and frees the prisoners held in Operation Dent. He denounced the rich and powerful, promised to restore the power of the people, and called on the masses to "take back your city"—with Poison revealing himself as "the ultimate Wall Street occupier, calling on the 99% to unite and bring down the elite of society." [1] This is followed by the film's take on people power: in a word it shows the trials and executions of the rich, the streets littered with crime and evil... A few months later, when Gotham continues to suffer from mass terror Meanwhile, Wayne successfully escapes from prison, returns to Gotham City as Batman, and gathers his friends to liberate Gotham City and prevent the explosion of the nuclear bomb. Batman confronts Poison and overpowers Poison; but Miranda steps in and stabs Batman - the social philanthropist who turns out to be the daughter of Ninja Russ: it was she who escaped from prison as a child, and Poison helped The one she escaped. After announcing that she was going to fulfill her father's will to destroy Gotham City, Miranda fled. In the ensuing chaos, Gordon disables the nuclear bomb's ability to be detonated remotely, while Selena kills the poison, leaving Batman to hunt down Miranda Tate. Batman tries to force Miranda to bring the bomb into the fusion device to stabilize it, but Miranda floods the device with water. Miranda died when the truck ran off the road, but she was confident the explosion could not be stopped. Batman used a special helicopter to hoist the truck to the outskirts of the city; the bomb exploded on the sea, presumably killing Batman as well.

Today, Batman is celebrated as a hero whose sacrifice saved Gotham City. Wayne is believed to have been killed in the riot. As his estate is divided, Alfred sees Bruce Wayne and Selena sitting in a cafe in Florence while Blake, an honest young cop learns who Batman is and inherits Batman Hole. In short, "Batman came back from defeat, emerged unscathed and continued to lead a normal life, with another person taking his place in his role of defending the system."[2] The primary clue to the ideological underpinning of this ending is given by Provided by Gordon, who at Wayne's (fake) funeral read the last words of Dickens' Tale of Two Cities: "I've done something much better than I've done, well Much better; I am going to a much better, much better resting place than I know."[3] Some film critics even take this quote as a hint: "[It] rose to the West The highest level of art. The film appeals to the heart of the American tradition, the ideal of a noble sacrifice for the masses. In order to be praised, Batman must humble himself, in order to find a new life, he must let go of his life/… …/ An ultimate Christ figure, Batman sacrificing himself in order to save others.”[4]

From this point of view, the Christ who retreated from Dickens to Calvary is really only one step: "For whoever will save his life will lose it; and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it. If a man gains the whole world What is the profit of losing your own life? What else can a man give in exchange for his life?” (New Testament Matthew 16:25-26) Is Batman’s sacrifice a repetition of Christ’s death? Isn't that notion weakened by the film's final scene (Wayne and Selena sitting in a cafe in Florence)? Isn't the religious counterpart of this ending the famously blasphemous idea that Christ actually survived the crucifixion and lived a long, peaceful life (in India, or even Tibet, supposedly)? The only way to salvage the final scene is to read it as the daydream of Alfred sitting alone in a Florentine café. A further Dickensian feature of the film is a depoliticized gripe about the gap between rich and poor - early in the film, Selena whispers to Wayne at a banquet dedicated to the upper classes: "A The storm is coming, Mr. Wayne, you and your friends better prepare early. For when it comes, you will be amazed that you think you can be rich and rich while leaving the rest of us destitute." Lan, like every well-meaning liberal, "worries" about this inequality and allows it to permeate the film:

"What I see in the film in relation to the real world is the idea of inequality. The film is

about /…/ The concept of economic fairness permeates the film, and the reason is twofold. First, Bruce

Wayne is a billionaire. This has to be pointed out./ .../ But secondly, there are many things in life where

we have to believe what we're told, and the economy is one, because most of us feel like

we don't have the analytical tools to know what's going on. /…/ I don’t think there is a

left or right perspective in the film. There is only a faithful

appraisal .”[5]

While audiences know Wayne is a super-rich, they tend to forget where his wealth came from: Arms factories plus stock market speculation, which is why, a stock-trading game of poison can destroy his empire - arms dealers and Speculators, that's the real secret behind Batman's mask. But how does the film handle this? Reinstate Dickens' archetypal topic: a good capitalist (Wayne) funding an orphanage against a greedy bad capitalist (Dickens' Stryver). In this Dickensian over-moralization, economic inequality is translated into "fraud" that deserves a "faithful" analysis, although we lack any reliable cognitive map, and such a "faithful" path leads to a A further parallel to Dickens—as Christopher Nolan’s brother, Jonathan Nolan (who co-wrote the screenplay) bluntly: “To me, A Tale of Two Cities is a The most tragic portrait of a civilization that can be recounted, recognizable. In Paris, in the horrors of France at that time, it is not hard to imagine how terrible and bad things could have gone.”[6] The film is full of vengeful populism The scene of the riot (a mob eager to kill the wealthy who had neglected and exploited them) is reminiscent of Dickens' depiction of the Reign of Terror, so while the film has nothing to do with politics, it "faithfully" portrays the revolutionaries As far as mad fascists are concerned, it defers to Dickens' novel, and thus provides

"a caricature of how a group of hard-minded revolutionaries rebels against structural

injustice . Hollywood is about the ideals of the existing establishment. Something to let you know - Revolutionaries are

savage monsters with a complete disregard for human life. While they have a liberating rhetoric about freedom, they hide sinister intentions. So

whatever their reasons, they're going to be wiped out .”[7]

Tom Charity rightly notes "the film's defense of the established establishment in the form of benevolent millionaires and honest cops". [8] In line with its suspicion of people's control over the situation, the film "shows a desire for social justice and a fear of what might actually happen under mob control". [9] Here, Karthick poses a clear question about why the image of the clown in the previous film is so popular: why in the previous film the clown was treated with leniency while the poison was treated so harshly executed? The answer is simple and convincing:

"The Joker demands a pure anarchy, critically exposing the hypocrisy of bourgeois civilization, but his

ideas cannot yet be translated into mass action. 's system poses a real threat . /

... / His power is not only his size, but also his ability to command and mobilize people to achieve a political goal.

He represents the pioneers, mobilizing politics in his own name Struggle, an organized symbol of the oppressed for structural change

. Such a force with the greatest potential for subversion cannot be tolerated by the system. It must be eliminated.

”[10]

Yet even if Poison lacks the charisma of Heath Ledger's Joker, there is one characteristic that distinguishes him from the latter: absolute love, the source of its ruthlessness. In one brief but moving scene, we see how the poison endures horrific pain and, in an act of love, saves young Miranda, recklessly and dearly for it (when he He was almost killed while defending Miranda). Karlsic has every reason to place this event in the midst of a long tradition from Christ to Che Guevara, which celebrates violence as a "work of love", as Guevara famously said in his diary: "Let I take the liberty to say, in a tone that seems absurd, that a true revolutionary is guided by a strong feeling of love. Without such qualities, a true revolutionary is unimaginable."[11] Here we meet It is not the "Christianization of Guevara", but the "Guevaraization of Christ Himself", that is, Christ's "shameful" words in the Gospel of Luke ("If anyone comes to me, if he does not love me more than whoever loves his parents, his wife, his children, his brothers and sisters, and his own life, cannot be my disciple" [Luke 14:26]) points in the same direction as Guevara's famous quote: "You may have to be rude, but don't lose your grace; you may have to break the flowers, but they don't stop growing in spring."[12] The assertion that "true revolutionaries are guided by strong feelings of love" should be consistent with Guevara put together the more "problematic" discourse of revolutionaries as "killing machines":

"Hatred is an element of struggle; relentless hatred of the enemy propels us and transcends the natural limitations of man ,

turning us into efficient, violent, selective, ruthless killing machines. Our warriors must be; a nation

without hatred cannot defeat a savage enemy.”[13]

Or, to quote again Kant and Robespierre: Love without cruelty is empty; cruelty without love is blind, and a fleeting passion loses its lasting edge. [14] Here, Guevara rephrases Christ's assertion about the unity of love and the sword: in both cases the underlying contradiction lies in what makes love lovely, above the fragile, mournful, purely sentimental The thing, precisely cruelty itself, is its connection to violence—a connection that elevates and transcends the natural limitations of man and turns love into an absolute drive. That's why, going back to The Dark Knight Rises, the only real love in the movie is the love of poison, the love of the "terrorist" tit-for-tat Batman.

Along the same lines, the figure of Miranda's father, Ninja Russ, deserves closer scrutiny. A fusion of Arab and oriental qualities, Rath is an actor of virtuous terror who fights against a degenerate Western civilization. He is played by Liam Neeson, whose screen image usually exudes a stately benevolence and wisdom (he's Zeus in The Clash of Titans), who also plays "The Clash of Titans" Qui-Gon in The Phantom Menace, the first Star Wars prequel. Qui-Gon was a Jedi Knight and mentor to Obi-Wan who discovered Anakin Skywalker and believed that Anakin was the chosen one to restore balance to the universe, but he ignored Yoda Master's warning about Anakin's unstable nature; Qui-Gon is killed by Darth Maul at the end of the film. [15]

In the "Batman" trilogy, Russ is also a mentor to the young Wayne: in "Batman Begins," he finds the young Wayne in a Chinese prison; he calls himself "Henry" Ducat" and offered a "road" for the boy. When Wayne was free, he climbed up to the Shadow League's stronghold, where Rath was waiting, even though he falsely claimed to be the servant of another man named Rath. Towards the end of the long and hard training, Russ explained that Wayne had to do everything necessary to fight the evil; he also revealed that they trained Wayne with the intention that he would lead the Shadow League to destroy Gotham City , because they believed that there had been utter depravity. So Rath is not a simple personification of evil: he represents a combination of virtue and terror, an egalitarian discipline against a fallen empire, and is thus (in the case of recent films) subordinated from Dune ( Dune's Paul Atreides continues in the tradition of Leonidas in "The 300 Spartans" (300). The point is, Wayne is his disciple: Russ built Batman.

Two common-sense accusations arise automatically here. First, there are horrific massacres and violence in actual revolutions, from Stalinism to the Khmer Rouge, so the film is clearly not purely engaging in an oppositional imagination. Followed by the opposite accusation: the actual Occupy Wall Street movement was not violent, and its goal was by no means a new reign of terror; the film is absurd and wrong insofar as the Poison Rebellion is seen as an outward extension of Occupy Wall Street's inner tendencies It reproduces the goals and strategies of the movement. The anti-globalization protests of the moment are the opposite of the savage terror of Poison: Poison represents the mirror image of state terror, a murderous fundamentalist sect that seizes power and enforces a reign of terror rather than the self-organization of the masses to triumph … What both accusations have in common is the image of repelling poison. The answers to these two accusations are multiple.

First, we should clarify the actual scope of violence. For the argument that the violent rabble's response to oppression is more horrific than the original oppression itself, Mark Twain, in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, made a Best answer: "The 'Age of Horror' has actually happened twice, as long as we're not too forgetful to see it this way. Once when killing people with passion, and when killing people with ruthlessness, killing without blinking an eye; A few months, another millennium; one 10,000 people, another 100 million. But it is the horror of that secondary 'terror', that , that fleeting horror. On the other hand, dying under a sharp axe in an instant is nothing compared to starving and freezing for a lifetime, suffering humiliation and ravages, enduring hardships, and slowly tortured to death. What does it mean to be struck to death by lightning in the blink of an eye, compared to being slowly burned at the stake? Each of us has been taught so earnestly that we feel frightened and grief-stricken when we think about that short-lived terror. Incomparable, but a city cemetery can accommodate the coffins of all the dead; however, the dead caused by that relatively long but real horror, even the whole of France, could not be buried. It was tragic and terrifying, but no one has ever taught us to see the catastrophe clearly, or given the understanding we deserve.”[16]

Second, we should demystify the issue of violence, rejecting the simplistic argument that twentieth-century communism used too much excessive brutal violence; we should be careful not to fall into this trap again. As a fact, this is of course horribly true; but such a direct focus on violence obscures the fundamental question: how wrong is the goal of twentieth-century communism itself, and what is inherently flawed in that goal so that those in power Communists (not just them) resort to unlimited violence? In other words, it is not enough to say that the communists "ignored the problem of violence": it was a deeper socio-political failure that led them to resort to violence. (The same goes for the notion that communists "ignore democracy": the whole purpose of their social change compels them to do so.) Not only does Nolan's film fail to imagine true people power, but even "truly" radical liberation movements themselves It is unimaginable that they still remain in the coordinates of the old society, so the real "people power" is usually such a violent terror.

Last but not least, it is too simplistic to claim that there is no potential for violence in Occupy Wall Street and similar movements. There is violence at work in every real liberation process: the film's problem is that it wrongly translates this violence into brutal horror. What, then, is the sublime violence, with which the most barbaric killing is only an act of cowardice? Let's take a detour using Jose Saramago's novel Seeing. The novel tells the bizarre events that take place in the unnamed capital of an unnamed democracy. When the morning of Election Day was marred by heavy rain, the voting crowd became uncomfortably depressed, but the weather improved in the afternoon and people walked to the polling place together again. But the government's relief didn't last long, as polls showed more than 70 percent of the votes in the capital were blank. Confused by this apparent abstention from citizens, the government gave them a chance to make amends, scheduling another election a week later. The result is even worse: 80% of the votes are now blank. The two main parties, the ruling party on the right and its main rival, the Centre Party, panicked, while the tragically overlooked left party presented an analysis claiming that blank votes were essentially for their progressive agenda. With the government unsure of how to respond to a modest protest but insisted there was an anti-democratic conspiracy, it quickly labelled the movement "pure, outright terrorism" and declared a state of emergency. With all constitutional guarantees in place, a series of intensified steps were taken: citizens were arbitrarily arrested and sent to secret interrogation sites, they forced the withdrawal of police and government stations from the capital, and blocked all passages in and out of the city, finally creating the their own terrorist leaders. The city continues to function almost normally, the people are miraculously united, and in a truly Gandhi-esque form of nonviolent resistance, every attack by the government is blocked... This, the abstention of the voters, is truly radical "divine violence" ', which provokes a brutal and frightening response from those in power.

Going back to Nolan, the Batman movie trilogy follows an inherent logic. In Mystery, Batman is also confined to a liberal order: the system can be defended in morally acceptable ways. The Dark Knight is actually a new take on two of John Ford's Western classics (Fort Apache and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance), It shows how, in order to civilize the Wild West, one has to "print legends" and ignore the truth - in short, how our society has to be built on a lie: In order to defend the system, we have to break the rules . Or, to put it another way, in Mystery of Shadows, Batman is just a classic image of an urban vigilante who punishes criminals where the police are powerless; the problem is that the police, the official law enforcement agency , has an ambiguous connection to Batman's assistance: while acknowledging its effectiveness, it nevertheless sees Batman as a threat to its monopoly of power and evidence of its own incompetence. Here, however, Batman's transgression is purely formal, embodied in acting in the name of the law, but need not be legitimized: Batman never violates the law in his actions. The Dark Knight changes those coordinates: Batman's real antagonist isn't the Joker, his enemy, but Harvey Dent, "The Knight of Light," the enterprising new District Attorney, an official vigilante, His frenetic struggle with crime led him to indiscriminately kill innocents, ultimately destroying himself. As if Dent were the legal order's response to Batman's threat: to resist Batman's vigilante-style struggle, the system generated its own illegal excesses, its own vigilantes, more violent than Batman, directly violated the law. So, when Wayne plans to publicly reveal himself as Batman, Dent does a poetic justice to the fact that he calls himself Batman: He's "more Batman than Batman himself," and he achieves The temptation that Batman can always resist. So, at the end of the film, Batman takes Dent's crimes against himself in order to save the reputation of the popular hero who is the embodiment of hope for ordinary people, and this self-erasing act contains a little bit of truth. : In a sense, Batman paid Dent back. His action is a gesture of symbolic exchange: first Dent himself takes on Batman's identity, and then Wayne, the real Batman, takes on Dent's crimes.

Ultimately, The Dark Knight Rises goes even further: Isn't Poison the ultimate Dent, his self-denial? Dent came to the conclusion that the system itself is unjust, and therefore, in order to fight injustice effectively, one has to turn directly against the system and destroy it. As part of the same move, Poison ditched the ultimate limit, ready to use all brutal savagery to achieve it. The appearance of such an image changes the whole constellation: for all involved, including Batman, morality is relativized and becomes an appropriate issue, something determined by circumstances: it is an open class struggle , when we are facing not just a frenzied mob but a mass rebellion, everything is allowed in order to defend the system.

So, is that all there is? Should cinema be categorically rejected by those engaged in radical liberation struggles? The situation is even more ambiguous, and we have to interpret it in a way that interprets Chinese political poetry: absence is as important as accidental presence. Recall an old French story: a wife complains that her husband's best friend is taking advantage of her, and it takes a long time for the surprised friend to understand that in this twisted way, the woman invited him to seduce her... This is Flo Id's Unaware of Negative Unconscious: What matters is not the negative judgment of something, but the fact that something is mentioned. In The Dark Knight Rises, the power of the people is here, presented as an event that takes a crucial step away from Batman's usual enemies (evil supercapitalists, thugs and terrorists).

Here we get our first clue: the prospect of the OWS (Occupy Wall Street) movement to seize power and establish a people's democracy in Manhattan is so obviously absurd, so absolutely unrealistic, that we can only ask one question: So, Why should a Hollywood blockbuster dream of it, and why should it evoke this ghost? Why even dream of the OWS movement erupting into a violent power grab? The obvious answer (stigmatizing the OWS with accusations that it hides a terrorist-totalitarian potential) is insufficient to account for the eccentric fascination of the prospect of "people power". No wonder what this power really does is to keep it blank, absent: it gives no details of how this power of the people works, what the people being mobilized are doing (recall that poison just tells people that they can do what they want everything - he did not impose his orders on them).

That's why an external critique of the film ("its depiction of the OWS rule is a ridiculous caricature") is not enough, the critique must be internal and must establish within the film plural symbols that point to real events . (For example, recall that Poison was not a purely savage terrorist, but a man of great love and sacrifice.) In short, pure ideology is impossible, the authenticity of Poison has to be in the text of the film leave a mark. That's why the film deserves a closer reading: the event - "The People's Republic of Gotham," the dictatorship of the proletariat in Manhattan - is intrinsic to the film, it is the center of the film's absence.

-------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------

Translated from EGS: Slavoj Žižek. "Dictatorship of the Proletariat in Gotham City | Slavoj Žižek on ' The Dark Knight Rises'." in: blog da boitempo. 8/8/2012.

[1] Tyler O'Neil, "Dark Knight and Occupy Wall Street: The Humble Rise" Hillsdale Natural Law Review, July 21 2012.

[2 ] Karthick RM, "The Dark Knight Rises a 'Fascist'?", Society and Culture, July 21, 2012.

[3] Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities, translated by Shi Yongli and Zhao Wenjuan, Beijing: People's Literature Publishing House, 2004, p. 327 pages.

[4] Tyler O'Neil, op.cit.

[5] Christopher Nolan, interview in Entertainment 1216, July 2012, p. 34.

[6] Interview with Christopher and Jonathan Nolan to Buzzine Film.

[7] Karthick, op.cit.

[8] Tom Charity, “'Dark Knight Rises' disappointingly clunky, bombastic", CNN, July 19, 2012.

[9] Forrest Whitman, "The Dickensian Aspects of The Dark Knight Rises", July 21 2012.

[10] Op.cit.

[11] Jon Lee Anderson, Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: Grove 1997, p. 636-637. [

12] McLaren, op.cit., p. 27.

[13] Op.cit., ibid.

No intuition is empty, and intuition without concept is blind."

[15] We should note the ironic fact that Neeson's son was a devout Shia Muslim, and Neeson himself often speaks of his beliefs about Islam of public conversion.

[16] Mark Twain, "The Connecticut Yankees in the Arthurian Dynasty", translated by He Wenan and Zhang Mei, Nanjing: Yilin Press, 2002, p. 81.

View more about The Dark Knight Rises reviews