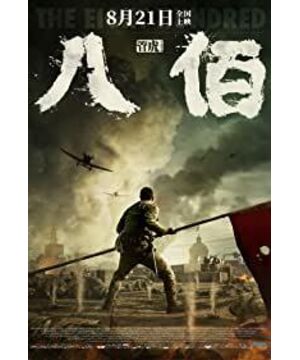

There is no doubt that Guan Hu's "Eight Hundred" will definitely be the most watched domestic blockbuster this year. Since the film was withdrawn from the Shanghai Film Festival last year and sent back for re-censorship and deletion, it has attracted great attention from movie fans. Unexpectedly, this year will finally be able to see the sun again, and with the reopening of theaters after the epidemic, the audience's enthusiasm for watching movies will be quickly ignited, and the record-breaking box office figures are believed to be just around the corner. As a historical war theme, the film selected the last battle of the Battle of Songhu in 1937. The Kuomintang "Eight Hundred Heroes" were instructed to stick to the Shanghai Sihang Warehouse and fought bravely for four days and four nights with fewer enemies and more tenacious resistance. This sensitive subject is enough to set off a storm of controversy. Whether this beautifies the Kuomintang is not the key, and I don't think it is the starting point for Guan Hu to shoot this commercial blockbuster. The point is that this film has set a dazzling benchmark for the industrial level of domestic war genre films with high-cost investment and advanced technology.

Rather than calling it a passionate anti-Japanese war film, I think it is closer to a group movie, where the ambitious director used numerous characters and clues to outline the complex national character under the war and turmoil. Soldiers who died heroically, civilians who escaped from the world, people from all walks of life who are affectionate and righteous, intellectuals watching the fire from the other side, young students who joined the army in anger, and so on. And this seems to be criticized by the audience. The narrative clues and viewpoints are confusing. Each supporting role has a very short playing time. Among the complicated characters, not many really shine.

The most amazing thing about the film is the setting of the two sides of the river separated by a river, showing the two worlds of war and peace in front of the audience. This illusory art set with the stage play not only highlights the absurd nature of the war itself (a political show), or sums it up in one sentence from the film: Behind all wars is politics. On the other hand, this setup also has an evocative political metaphor, even if it is not necessarily a superficial symbolic reference to the mainland and Taiwan. As a result, the film gradually extended from the original main line of the heroic struggle of 800 heroes to the various voices of the people on both sides of the river regarding the war. This narrative of constantly shifting focus occasionally returns to the main theme of the Chinese nation's unity against foreign enemies in the subsequent passages of heroic sacrifice. However, there are many problems in the design of the night crossing bridge from the second half to the climax, and bitter and sensational routines continue to emerge, which may be related to censorship and deletion, making Guan Hu's ambitious work into a patriotic propaganda and education film with a vague focus.

View more about The Eight Hundred reviews