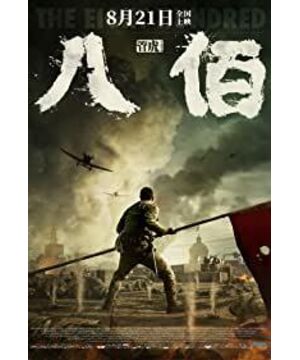

"Eight Hundred" is a movie about watching and being watched, as many film critics have said. In the eyes of Lao Jiang and the foreign powers who are not too big to watch the excitement, "Eight Hundred Heroes" was originally an exhibition competition, and the film brought the logic of watching and being watched to the extreme through the screen of Suzhou River.

But what few people mention is that "Eight Hundred" is still a "Yuan-Anti-Japanese War film", which is dedicated to dismantling the ISA of anti-Japanese war films. The most important thing here is the distance between the protagonist group and the eight hundred heroes. The motif of the rabble doing great things is not a new thing, the common routine of Hollywood personal heroism, "The Piano of Steel" and "Old Cannon" are even more familiar. However, doesn't it feel abrupt that this postmodern routine is inserted into the anti-Japanese war film? Obviously, this method is to please the contemporary audience. People don't like to watch model dramas, but they like to add anti-hero flavors and engage in "human weakness". This has been the mainstream of literature and art since the 1980s. However, the strategy of "Eight Hundred" is that "human nature" belongs to the protagonist group, and the eight hundred heroes are still playing model plays, and the division is clear. Covetousness and fear of death + lsp, that is a matter of Hubei farmers, Northeast local ruffians, Shaanxi veterans, and Shaoxing masters. The eight hundred warriors are all party-state elites armed with German weapons and ideological, with a halo. The image of the Eight Hundred Heroes has not developed from the beginning to the end. It is purely a tool to promote the thinking of the protagonist group; but the protagonist group has no promotion for the narrative. Get rid of the rabble and shoot the film, but it is no different from the Taiwan version. What a difference. Ironically, the commissioner said, "Let the motley army go to death," but the director really let the protagonist group be the cannon fodder. From this point of view, the story of the protagonist group is completely parasitic on the drama of the war of resistance against the Eight Hundred Heroes.

So, isn't the protagonist group also "watching a movie"? In fact, these Hubei guys were called by the local party headquarters to support the front line, and their original purpose was to experience "Great Shanghai"? As a result, I didn't expect the national army to be defeated, so I was caught in the Sixing warehouse in a confused way. It's like going to Disneyland happily, only to be turned into the Martyrs Cemetery halfway. It is said that the audience is going to scold Niang Xipi at this time, but the director arranged for you to be obedient, because if you look closely, this Martyr's Cemetery is quite good, with a VR experience hall, and even includes the Disneyland project, which can be separated by On the Suzhou River screen, you can watch Belarusian prostitutes, Girl Scouts, and Beijing opera. By the way, I received the ideological education of the party-state elites, and experienced the epic war. As a result, when I walked out of the movie theater, I felt very rewarding and received five-star praise. I will come again next time.

Who is watching this four-line warehouse defense battle? The first is the protagonist group, then the patriotic masses on the other side of the Suzhou River, then the foreign powers and Lao Jiang floating in the air, and finally the spectators sitting in the cinema. We spectators are the luckiest, because we experience all the VR projects in full, experience all the eye overlap, so we have to pay. Are we going to the cinema for a pure anti-war film? We've seen enough. In fact, you also came for the spectacle of the foreign market in Shanghai, for the sensational effect of the media hype, and for the kind of hooliganism in "Old Pao'er", because you feel that you have the same odor. In other words, you just came to see it, and the director understands it very well, so it will satisfy you.

In fact, there is more to watch in the film, and that's how the nationalist ISA captures you. Don't the Americans in the airship and the professor on the balcony have binoculars? This kind of reference to looking is simply naked. Finally, the professor took out his rifle and naturally changed from a telescope to a scope. You are standing in the four-line warehouse and looking at Belarus, and the opposite Belarus is also looking at you. Isn't this kind of staring ambiguous enough? It is true that the Girl Scouts sent the flag, but the flag wrapped around the chest is probably the director's own obscenity. The protagonist group looked at the girl's beautiful back, and immediately thought of the crisp breasts, the national flag that had been in contact with the crisp breasts, the broken party-state of our mountains and rivers, and our veterans were still virgins. Aren't you excited? "As soon as you look at it, your head is confused." Another allegorical fragment is the image of Zhao Zilong in Changshan, from the inexplicable theory of Zhao Zilong's superiority over Guan Erye (country vs brothers), to the fantasy of the Dragon Boat Festival, and then to the fantasy of Xiaohubei , the virus of romantic devotion spreads among individuals, while the troupe across the river continues to perform to spectators. However, what was left to the 800 warriors in the end were the plaques on the stage with "Long Qi" and the "real Chinese" blurted out by the commissioner. On the contrary, the old drama sung by the old hooligan in the northeast on the roof of the building in the snow is more likely to remind people of the part that Ah Q sang before his death when he was confused by the revolution and was shot to death.

Of course, in the end, there is also the director's look. Is the reporter Fang in the film the incarnation of the director? If so, that would be too narcissistic. Obviously, what the director wants to maintain is the image of a calm and neutral recorder, he does not comment, but records everything with a black and white film machine for people to see. As far as the film's maze of seeing and being seen, he certainly succeeded. But creating a nationalistic spectacle does not make one immune to politics, because the camera is neutral, the photographer is not. The behavior of this reporter Fang, put it in 1937, a proper traitor, a group of iron-blooded hoes came to the door every minute, and the film was all for you! (Thinking about Zhou Zuoren, it's really wrong.) This is because the agency is too clever, and it has mistaken Qingqing's life.

Finally, I would like to add that this film is a rare anti-war film without a TG. (Perhaps the street actor who played "Put Down Your Whip"?) After all, the Eight Hundred Heroes are still the subject of the National Army's Anti-Japanese War, which is essentially a remake and mockery of the nationalist narrative of the Taiwan puppet government's mobilization and suppression of the rebellion. Think about who Lao Jiang is, a big fan of Mussolini, and fxs' mass mobilization relies on the capture of middle-class entertainment culture? The more they lack the support of the lower class, the more they need this romantic narrative to arm their minds.

Are the Eight Hundred Heroes heroes? of course. The nationalism of the Eight Hundred Heroes, and the nationalism of the patriotic masses in 1937, okay? Of course, because that is the struggle of the oppressed nations to resist imperialism and achieve self-liberation, and there is nothing more glorious than this in the world. But can audiences today understand the implications of nationalism in 1937? I think it is very difficult. There is no other reason. China has become stronger, and it is the second largest economy in the world. We have long lost the concept of "imperialism". So, do we really need Disneyland-style nationalism? I don't think it is necessary. Guan Hu's subtle words and righteousness expressed in a yin and yang manner here still have merit: he didn't want to insult the martyrs, he was just mocking the spectators.

View more about The Eight Hundred reviews