Driver plays an outrageous comedian in this musical full of male and patriarchal rage. He is the center of the film, but his role is surprisingly ambiguous.

Originally published in The New Yorker by Richard Brody Translated by Rowena (abridged)

When Martin Scorsese thinks superhero movies aren't "cinemas," he's not referring to their storylines, but their production models: over-management, studio-controlled franchise development and protection , namely "Intellectual Property". But artistic freedom is not only manifested in the absence of contractual constraints, but equally important is the inner freedom—a director who is prepared to make a film at the risk of going against business. Despite being independent of the studio system, many directors create films as if they had a studio in mind. Leo Calax's "Annette," a musical based on the stories of brothers Ron and Russel Mael (also known as the Sparks), who also wrote the song (cards) for the film. Lax added a few extra lines to that). It's a brilliant and bold film in many dimensions, and yet it's not entirely satisfying—it doesn't reframe the film's many possibilities the way Karax's best films do, because The studio in Karax's head was projected by Adam Driver.

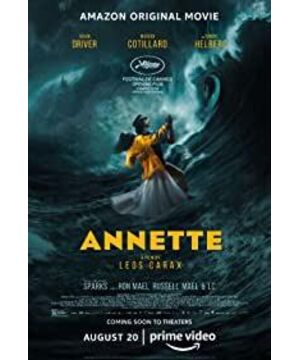

At the beginning of the film, a voice like Karax asked the audience not to "sing, laugh, clap, cry, yawn, boo, and fart", and he also reminded people that "breathing is not allowed during the viewing, so Now, take one last deep breath." Karax first appeared on screen, manipulating the control panel in the Santa Monica studio where the Sparks were performing. Carax's daughter, Nastya Golubeva Carax, is in the blurred background, and when Carax is ready to prompt Sparks to start, he calls her daughter to his side. The Sparks responded to Karax's request with "SO MAY WE START" and left the studio with four female backing vocalists, joined by three main cast members, Adam Driver, Marion Cotillard and Simon Helberg. The group sang Cross the streets in a soothing rhythm. Driver and Cotillard took clothes from others, transformed into their characters, and headed to the show—Henry to the Orpheum Theater, Ann to Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall.

This opening is the pinnacle of the film's joyous atmosphere, where a gloomy story of male vanity and arrogance begins after a happy opening of a riff. A traditional tragic story is deconstructed into a tale of wanton destruction and a moral tale of escape. The story is a little weak, and most of the play is set in Los Angeles and its surrounding areas, with song arias expressing emotions instead of dialogue to express the heart of the characters. Henry McHenry (Driver) as "the Ape of God", a slightly offended, world-famous talk show actor who meets Cotillard's character Ann before the opening scene and falls in love with her . Ann is an opera singer, with Simon Helberg playing her accompanist. Ann and Henry soon married and raised a little girl named Annette together, but the relationship destroyed Henry's personal life and work. He felt bad about being domesticated by his family, and then became extremely offensive during the performance. As a result, his career plummeted, while Ann's career soared. He became self-indulgent, reckless, and furious, culminating in Ann's death in an accident. Annette, raised by Henry, was a child prodigy, a gifted singer, and Henry exploited her children until she became a public figure and an international superstar. But (to avoid spoilers) Henry's lingering fury makes him guilty at a time when he desperately needs Annette's show to keep going to support himself.

Henry is the central character of the film, but his role in the film is surprisingly ambiguous. Annette is a character like Dostoevsky's anti-psychological portrayal. From this perspective, Annette resembles and rivals one of the greatest films in world cinema, The Pickpocket: in this Robert Bresson work, completed in 1959, A philosophical criminal deliberately resists, and finally finds a purifying and sublimating redemption through love in the historic final act - something that Annette's final act clearly echoes. The protagonist in Bresson's film reveals his motives in dialogue, but Henry hints at his inner tangle only slightly through his onstage rants and his simple theatrical behavior. His songs have few psychological descriptions, just explicit statements of motivation, with the only exceptions being his references to "the abyss" and his gaze at his own deadly actions. It's a vague comment mixed with gestures, and he both praises and dismisses the antihero.

This dramatic obscurity requires the interpretation of the performance, the basic collaboration of director and actor. That relationship is at the heart of "Annette"; it's why it has all the good qualities of Karax's films, but is nowhere near the best of Karax's. Karax said in an interview decades ago that the greatest privilege of making a movie is being able to work with actors. He's made some actors, contributed to the screen debuts of Julie Delpy and Denis Lavant (Denis Lavant), and also sent Juliette Binoche (Juliette Binoche) to the altar. In working with them, they are the embodiment of Karax's art, and Karax is free to photograph them. Quite the contrary, in "Annette," the Driver (who also produced the film) is the star, not the work of Karax. Karax said he chose Driver to star in his own film after watching his breakthrough performance in Lena Duham's "City Girl." But "Annette" was delayed until Driver finished filming "Star Wars." Meanwhile, Driver has starred in major roles in the likes of Scorsese, the Coen Brothers and Baumbach. Driver has come to represent both the myth and authority of mainstream Hollywood and the enduring artistic tradition of cinema. Such a double halo seems to hinder Karax's creation. The image of Henry can be ridiculed, disrespected, and even scorned, but Karax gives the story, and the character in particular, a godly respect at the same time. As a result, he gives the impression that he is showing the driver rather than changing it.

Part of the problem is the nature of the Driver's advantage as a performer. Lawan, the protagonist of several Karax films such as Sacred Motors, is a virtual chameleon whose transformation is first and foremost physical, like silent film actors like Lon Chaney and Emil Jannings. Rawang is also a true acrobat, even in his breaks he is still in motion. The originality of Driver's acting style, by contrast, lies in its classic Hollywood character: Robert Mitchum, like Robert Ryan, is always relentlessly presenting himself in a way that the director he works with would love, which in turn Become him playing himself. However, Rawang's performance is internalized and symbolized, with or without exaggerated costumes, it will not affect his excellent performance, while Driver is externalized, dramatic, literal, and closely related to realist performances . Driver himself explained the paradox of his performance in "Annette": "Even though it looks surreal, I can't be surreal." So, the revelation of Driver's transformation and Henry's inner workings falls entirely on the card Lax there, but Karax never got close enough to Driver (both in words, in camera, figurative and dramatic) to break out of Driver's familiar (albeit good) demeanor and bring the actor to his knees in the gravitational field. Karax's approach to the Sparks brothers' songs with the same respect for Driver also proves a limitation. In a sense, musicians are the most severe examination of a director’s art, because the effect of music will go against the director’s creation—musicians have done a lot of artistic creation, and directors often choose to be neutral and only record the sound in the form of a documentary, lest Cinematic imagery of oneself is considered to be a hindrance to the art of music. In Annette, Karax's cast mostly sings during long-travel footage, which doesn't reveal much about the character of the actor and director. Karax doesn't make the performer's presence loom, or appear to be off-screen, and he doesn't even use his vocals well. In this regard, the effect of having the instrumentalist's voice enter the soundtrack like a classical Hollywood musician is neither fully realistic nor fully stylized. There is a forced, depersonalized humility in the song segment. Instead, much of "Annette" can be summed up in one fatal word (indicating Karax's self-restraint of the screenwriter, composer): Illustrative.

Still, Karax's account is more vibrant and seductive than any other filmmaker.

But much of Karax's inspiration for Annette is in the settings, decorations and details. The sex scene in which Henry lifts his head from Ann's parted legs and sings is astonishing and alienating, and Henry's performance is not obsessive or enjoyable, but eccentric. Baby Annette is represented by a series of puppets whose faces always evoke Rawang. Every time I see Annette, there is always a sense of dizziness, but Karax does not use this skill very well. Although Annette is the protagonist, the child's mental activities are as difficult to understand as those dolls. Karax also did not enter Ann. Annette is a film about Henry, and through Henry's arc, Karax's eagerness to express himself is satisfied by the story of the Sparks—but instead of reinforcing each other, the two inhibit each other.

Henry wields his contract like Lenny Bruce wields his trial records, but unlike Bruce, he never goes into any detail, using the document only as a prop (Henry then adopts another of bruce's demeanor, who acts like a A priest who sprinkles holy water generally shakes his microphone.) "Annette" proves a hidden casting adage: Never let a non-comedian play a comedian, because being funny is the same as being able to sing. Actors can't learn humor, and it's impossible to drive other people's humor into the soundtrack. Driver threw Henry's performance in the spirit of the game, but presented an impressive character, not a comedic one. Instead, he just acted like a comedic character.

When Henry's career started to go downhill, his anger grew, he scared Ann, and he joked about killing Ann in a low-end theater in Las Vegas, which really offended the audience. Henry finally explained that the way he turned to the violence of reality was his surrender to "the abyss": "I set my eyes on the abyss." Perhaps, let such an artist tell the truth of what he (always "he") sees in the abyss Courage is required. Perhaps his Dostoevsky-esque gaze into the abyss on stage is a representation of real danger—an artist full of horrific ideas that can’t help but talk about putting them into practice. Perhaps it is the unjust sacrifice that society (and more commonly, women) makes to expose these horrific truths. Perhaps this cycle of horror is itself the abyss, the truth of male vanity and violence, and ultimately (spoiler warning) makes Annette work for her own disappearance from the public, in the process transforming her from a woman serving her father's exploitative needs The puppet, turned into a flesh-and-blood child.

"Annette" is both a tribute to and a denial of the embarrassed, arrogant male artist; an amoral drama and a moral drama, an allegory of personal redemption and social purification through singing metaphors. Annette, not Henry, is the bravest truth-teller in the film. Her supernatural talent, her beautiful, unspoken singing voice, not ethereal forms of abstract beauty, but her efforts to express her unspoken fears—created an audience for her, and the audience became the voice of her when she was finally able to express herself in words. Witness in time of fear. The concept is fantastic, and the Sparks brothers and Karax are very sincere in bringing it to life. But without Karax's typically unbridled imagination and candid confrontation with performers, Annette is no longer inexperienced, but just a concept.

View more about Annette reviews