I believe in this story, and I was so amazed by Tao’s last solo dance in the snow that I couldn’t speak for a long time—this woman who was pushed by the times and made two wrong choices in succession did not show a trace of resentment on her wrinkled face. and panicked look. Before going out, she also made dumplings, and there were a lot of dumplings, and the middle one had the edge of the wheat ear. This move obviously shows that she has firm hope and sufficient confidence in the return of her old friend, so even if the time has passed, there is no need to resent and panic. Tao is so optimistic, I think, because of her 100% trust in the land under her feet. Their roots are rooted here, where else can they go? Compared with Tao, who stayed in Fenyang from beginning to end, those who were wandering outside had to face the problem of defining their personal identity first, and they encountered difficulties without exception.

We know that Jia Zhangke's creation was influenced by Italian neo-realism from the very beginning, using dialect as a means to pursue a realistic style. In Mountains and Rivers Old Man, the use of dialect goes beyond the realism and becomes a metaphor for personal identity, especially in the character Dale.

To Le was born in Fenyang. After his parents divorced, he followed Jin Sheng, who was engaged in venture capital in Shanghai, to attend an international primary school. In 2014, when he returned to his hometown to attend the funeral for his grandfather, he was already a city child in a suit and a scarf. He doesn't speak Fenyang dialect, but he speaks Shanghai dialect very smoothly. When he made a video call with "Mommy" (stepmother), he changed his usual prudence, and his tone was friendly and fluent. As a child who migrated from the county to the city, I am happy to use the forgetting and learning of dialects to redefine my identity - Shanghainese. Shanghai and Taoben are not related, but later they became related because of Dale, and later, it used the method of assimilation to slowly dissociate this relationship. Tole leaves Shanghai for Australia, isn't it a cycle of this process? As the story draws to a close, Dale only remembers that his mother's name is Tao, which means wave. From Tao's point of view, this is the gradual deprivation of motherhood.

Time comes to 2025, and Dale, who has been immigrating for 11 years, has grown into a young man with a sad face, like a repetition of the previous story, he speaks authentic Australian English and forgets the Chinese language. (We put "country" into the category of "world", and both Australia and China are considered "localities", and both English and Chinese can be regarded as "dialects".) Tole can only speak English, but Jinsheng's English is not good, so they use Google Translate to talk on weekdays. For both father and son, each other is alienated into mechanical electronic equipment and software, and real communication cannot be achieved. In order to have an in-depth conversation with her father about her future, Dale invited a Chinese teacher to help her, but she withheld the key information in the conversation out of consideration for Le's safety, resulting in a complete failure of the communication attempt. The communication medium between father and son, whether it is an emotionless machine or an emotional person, as long as there is such a "third party", it is impossible for the other party to understand their own thoughts. In this sense, they have lost each other.

In the process of following Jin Sheng's migration from Fenyang to Shanghai and then to Australia, Dale gradually lost his mother and father (he once told his classmates that he was a parentless test-tube baby), and the loss of national language , then erased his Chinese identity. However, the bunch of keys hanging around his neck, the familiar scenes that appeared like ghosts in his mind, and the father who was full of Fenyang dialect and acted like a big father reminded him all the time: don't forget to play Come. The divisiveness of biological genes and cultural genes has led to the dilemma and tragedy of Dale. He wants to explore who he is and what he can do, but there is always nothing he can do or escape from the battle. In the end, he can only develop an incoherent love in despair. .

From the county seat to the city to overseas, the language used in Tole has also changed from Fenyang dialect and Shanghai dialect to Australian English, and we know that he has a trait or habit of forgetting language, the new and the old cannot be Compatible, picking up one must also drop one. This may be the symbol of the rapid change and transformation of their generation's identities, resulting in gradual blurring and loss. On the other hand, is this kind of change and transformation out of their active choice? Obviously not. What they play is the role of sacrificing the victims of the age. I remember that before the official confrontation between Lezai and Jinsheng, he once faced the sea and said a few words of Fenyang: "Yes."

Tole's predicament stems from his personal identity, as does the predicament of Tao's two old friends, Liang Zi and Jinsheng.

The 1999 passage recounts the love triangle between Tao, Liang Zi, and Jin Sheng. Jinsheng belongs to the trend of the times. After the reform and opening up, he accumulated huge wealth through various means. The dazzling red car made in Germany is a naked symbol. Later, he also sold the coal mine and became the boss of Liang Zi, his rival in love. In the end, Tao chose Jinsheng, a "coal boss" who cared about people, instead of Liangzi, a "miner" who cared about people. In Fenyang, Jinsheng and Liangzi, who were classmates in junior high school, were redefined and divided into classes by the hurricane Chinese society. Tao's choice, as an integral part of the choice of the times, is announcing that money and capital have achieved a stage. Sexual victory.

Liang Zi lost to Jinsheng, a "high-end person" who got rich first, and then decided to go out to the province. Although there is an element of anger with Tao (expressed as refusing to say "goodbye"), there is also no lack of determination to stand out and not come back. The cruelty of Chinese society at the turn of the century was that one step behind might never catch up. Therefore, we can see that Liang Zi, who came to other provinces, has no other choice or way to go. He can only go back to the coal mine and resume his old business. The difference is that he used to manage lamps, but now he goes to the mine. The reason for leaving is to change, but the result is to repeat the original identity life.

Different from Liang Zi's stagnation, Jin Sheng kept changing his identity. At the end of this section in 2014, he immigrated to Australia from Shanghai. Later, we learned that in the anti-corruption campaign in China, he fled abroad. In 2025, the lifestyle of middle-aged Jinsheng abroad is very similar to that of retired old cadres in small counties in China. They get together with their neighbors on weekdays, play chess, talk about the past, and get by. On the surface, his situation was much better than that of Liang Zi in other provinces. However, when he was wearing a gray coat, a vest, and carrying a tea cup, walking alone on the blue seaside, the picture that popped up in my mind turned out to be the tiger Liang Zi saw on the roadside after seeing the doctor— It was locked in a cage and looked restless. Liangzi was imprisoned by the pressure of survival in other villages, and Jinsheng was imprisoned by the unacceptable conditions of other countries. Whether it is the elevator of Liangzixia Mine, or Jinsheng's luxury sea view room, they are all deformations of the cage.

Personally, I think that the ever-expanding identity differences caused by money are being stitched together here, and regardless of the moral judgment, the two of them, like the director, are "Fenyang boys" in a foreign land. Except for the homeland, the other country is full of cages, and then Liangzi lost his life and Jinsheng lost his son. Such an absolute expression is probably related to the director's own nostalgia. It is no wonder that some people see Jia Zhangke's mid-life crisis. Daile lost their identities during the migration, while Liang Zi and Jin Sheng were soberly aware of the essence of their identities while they were wandering. Their youth and freedom were all placed in that dusty northern town. Their predicament lies in I have it in my heart, and then let the world become a corner. When arguing with Dale about freedom, Jinsheng sighed at a pile of real guns like toys. Now the law allows individuals to buy guns, but they can't even find an enemy. Here and in 1999, an intertext was formed. He once tried to buy a gun to kill Liang Zi, his love rival, but the domestic laws at the time did not allow it. The mountains and rivers have changed, and the old people are no longer. The level of sadness in this scene is no less than Tao's solo dance in the snow.

Going back to the source, Jia Zhangke's thoughts on the predicament of the identity of the wanderer have begun to emerge from Xiao Shan in "The Hill Comes Home" (1995, short film) when Xiao Shan cuts off his long messy hair on the streets of Beijing. "Old Man in Mountains and Rivers" continues this kind of thinking, and puts all the homesickness accumulated for 20 years into it. I understand how small the chances of Jinsheng and Dale going home are, but I still believe in Tao's hope and hope that Director Jia and his characters can find their final destination.

Finally, I borrowed a sentence from my classmates to end this nonsense article: "If you can go back, who doesn't want to go back?"

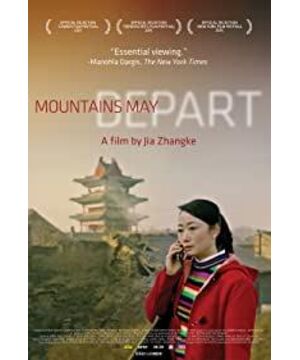

View more about Mountains May Depart reviews