Excerpted from The Sublime Object of Ideology (Revised Edition) Translated by Ji Guangmao

first part

How did Marx invent the omens?

9. "The law is the law"

[…]

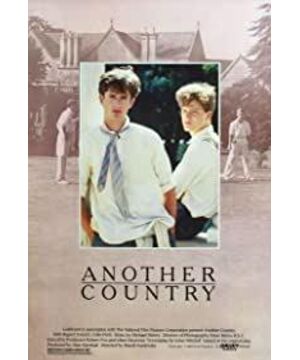

What distinguishes Pascal's "custom" from the bland behaviorist wisdom ("your actual actions determine the content of your beliefs") is the paradoxical identity of belief before be-lief: The subject first follows a custom, then believes something, but knows nothing about it, so final conversion is only a formal act (forma lact) by which we realize that we are Really believe something. In other words, what the behaviorist reading of Pascal's so-called "customs" misses is the crucial fact that external custom is the material support that always supports the subject's unconscious. The main achievement of Marek Kaniveska's (40) film "Another Country" is its sensitive and refined approach to the issue of conversion to Communism , the precarious identity of "believing something but knowing nothing about it".

Another Country is a film based on a true story about the relationship between two Cambridge students. One student was the communist Judd, whose real model was John Cornford, the icon of Cambridge left-wing students who died in Spain in 1936; the other was Guy Bay, a well-off gay man. Nate (Guy Bennet), who later became a Russian spy. He recalled the entire story to the British journalist who interviewed him in Moscow, his exile. Guy's real prototype is, of course, Guy Burgess. The two students were not having a sexual relationship, and Judd was the only one who had no sense of Guy's charm (Judd was, as Guy put it, "an exception to the Bennett rule"): it was for this reason that Judd became Guy's point of his transferential identification.

The story takes place in a 1930s "public school" environment: there is patriotic rhetoric and the fear of ordinary students for their student leaders ("the gods"); A light-hearted activity; there's a coterie of funny parody that hides an unknown world. There, extremely lewd pleasure prevails. Extremely lascivious pleasure first manifests itself in the intertwined web of gay relationships. So the real fear lies precisely in the heavy pressure of such pleasure. Because of their jobs, Oxford and Cambridge in the 1930s provided the KGB with extremely rich talent resources: not only because the children of rich families lived a leisurely life during the economic and social crisis, and thus gave birth to "criminal complexes". "(guilt complex), and because of this suffocating atmosphere of pleasure, and the heavy tension caused by such an atmosphere of pleasure. Only by rejecting this pleasure (which is what "totalitarianism" calls for) can this heavy tension be resolved. In Germany, it was Hitler who knew how to take the place of this appeal; in Britain, at least among the elite students, the KGB headhunters were best at it.

What is worth mentioning about this film is the way it depicts Guy's conversion to the Soviet Union: its sophistication is confirmed by the fact that it does not directly depict Guy's conversion to the Soviet Union, but shows it in full detail. That said, the flashbacks to the 1930s, which make up the bulk of the film, come to an abrupt end after Guy's conversion, even though Guy doesn't know anything about his conversion. The film omits the formal act of conversion with great refinement. It suspends the flashback in a situation that is very similar to the situation in which someone has fallen in love without knowing anything about it, and it is because of his job that he gives his love a form : Takes an extreme dog-wise attitude towards the person he loves and launches defensive attacks on the person he loves.

Look closely, what is the ending of this movie? There were two responses to this suffocating pleasure situation, and the two responses were diametrically opposed: On the one hand, Judd gave up pleasure and openly admitted that he was a communist, and for this reason he could not become a KGB agent. ; Guy, on the other hand, becomes an extremely depraved hedonist, but his game begins to fall apart. The "gods" shame him with ritual beatings. He was ritually beaten after his nemesis, a patriotic career seeker, revealed that Guy had entered into a gay relationship with a young student. Guy therefore forfeited the opportunity to be promoted to a member of the "Gods" the following year. At this point, Guy realized that the key to getting out of this unsustainable situation was his transferential relationship with Judd. There are two details that hint at this subtly.

First, he rebuked Judd for not being freed from bourgeois prejudice. Although Guy speaks of equality and fraternity, he still believes that "some people are better than others because of the way they make love". In short, the subject he captures is the subject to whom he has already empathized; he empathizes because of his own inconsistencies, of scarcity. Second, he showed the naive Judd the mechanics of empathy. Judd believed that his belief in communism was the truth, a belief that came from his in-depth study of history and the writings of Marx. Guy replied, "You are a communist, not because you understand Marx; you understand Marx because you are a communist!" In other words, Judd understands Marx because he It is assumed that Marx is the holder of some kind of knowledge that enables one to know the truth of history. It is the same with the Christian believer: the Christian believer does not believe in Christ because the theological arguments convince him, but on the contrary, he has a good understanding of the theological arguments because he has been bathed in the mercy of his faith.

At first glance, this seems to be the case, and the above two details tell us that Guy is on the verge of freeing himself from his empathy for Judd (he captures Judd with his inconsistency, and even reveals the mechanism of love), but the real situation is still quite the opposite: the above details only prove that "those in the know are lost", that is, what Lacan calls "les non dupes errent" (41), what's going on. Precisely as a "knower," Guy falls into the empathy trap: his two accusations against Judd only make sense in a context where he and Judd have established an empathy. Emotional relationship. It's the same thing as a psychoanalyst: the analyst's trivial weaknesses and mistakes are enough to make him happy, because the transference is already at work.

Just before Guy converted to the Soviet Union, he found himself in a certain state. This state, this state of extreme tension, is best expressed in the detail that Judd first accuses him, and then he responds to Judd's accusation. Judd blamed Guy, saying that he had only himself to blame for messing things up. If he had acted with a little more care, if he could have concealed his homosexuality, instead of showing it all over the place with arrogance and arrogance, there would not have been a nasty revelation that would have led him to ruin. Guy's response to this accusation was: "What could be more deceptive to a man like me than a utter rambunctiousness?" Of course, this is exactly what Lacan gave to the "deception in a certain human dimension" (deception in its specifically human dimension). By this definition, we resort to truth to deceive the other: in a world where everyone is looking for the real face hidden under the mask, the best way to lead others astray is to put on the mask of truth ( wear the mask of truth). But it is impossible to maintain the coincidence of mask and truth: not only does this coincidence make us "in direct contact with our fellows", it makes the situation unbearable; all communication is impossible, Because through this disclosure, we are completely isolated. A necessary condition for successful communication is that the exterior maintains a minimum distance from the hidden rear of the exterior.

So the only way out is to escape into the belief in a transcendent "other country" (communism), that is, to believe that there is an "other country"; to escape into a conspiracy, to become a KGB agent. This introduces a gap between masks and real faces. In the final scene of the flashback, Judd and Guy cross the campus together. By this time Guy had become a believer: his fate was sealed, even if he knew nothing about it. His introductory quote — "Wouldn't it be wonderful if communism existed?" — revealed his beliefs. At that time, he was still transferring and transferring this belief to others. We then stepped directly into exile in Moscow, decades later, where the only leftover of enjoyment linking the old, crippled Guy to his homeland was a memory of cricket.

View more about Another Country reviews