Author: Richard Brody

In 1939, Herman Kevich was a forty-two-year-old screenwriter. He was widely praised in Hollywood not only for his dialogues for films, but also for his actions in life. In his nearly 15-year career, he worked with Joseph von Sternberg and his friend Marx brothers at Paramount, and successfully wrote "Dinner" and "The Wizard of Oz" at MGM. For the latter, his idea was to shoot Kansas in dim black and white and Oz in color. But he is best known as one of the great figures in the film industry. He moved from New York to Hollywood, where he was the first drama critic of "The New Yorker" and a member of the famous Algonquin Roundtable. He brought the cynical frankness and sharp bluffing spirit of that group to Film industry. On committees and cocktail parties, he was known for his knowledgeable insights and unpredictable politics (he took great risks to write an anti-Hitler script in 1933, but he opposed the US participation in the second time The World War, even calling himself the "extreme Lindbergh"), is also known for his style of expressing these insights. He is also habitually drunk, arrogant, and known for creating confusion and verbal abuse. His work habits are also notoriously suspicious: As a compulsive gambler, he spends a lot of working time betting and listening to race horses; he chats with people on the phone all day, becoming a social whirlwind. He ridiculed and despised his boss, he would be fired for every job, and he did not resign. By the summer of 1939, when he was unemployed, he discovered how eagerly he needed it when a twenty-four-year-old Hollywood rookie named Orson Wells offered him a job.

Wells, prolific and precocious, became a stage star at the age of sixteen, and became a director of mainstream theaters at the age of twenty. In 1937, he became the co-founder of the Mercury Theatre (with John Hausman); at the age of twenty-three, he became Radio star, notorious for broadcasting "World War" in 1938, this story tells of an invasion from outer space, told in the form of a fake news briefing, and many listeners mistakenly believe it is true. He also made two independent films. In the week of his 23rd birthday, he appeared on the cover of Time magazine. However, Mankiewicz is a Hollywood insider, while Wells has been disgusted by the film industry, resented and ridiculed because of his youth, his reputation, his intellectual temperament and his contractual freedom. He signed a contract with RKO (雷电华) studio, where he was the producer, screenwriter, director and actor of two films. For these two films, he was the only one among the filmmakers in Hollywood studios. The final editing can be done. He initially asked Mankiewicz to write radio programs on his behalf, but their collaboration soon changed, and Wells recruited him as a co-writer for the first film.

Their collaboration, and the resulting movie, "Citizen Kane", was hailed as one of the greatest movies of all time even before it was released. A story about how a young heir turns himself into a newspaper tycoon and a national figure, builds and destroys his own empire, it has become a symbol of aesthetic and intergenerational change in the history of film, it makes Wells and Will Behind the representative of Si became the focus of the world movie. Wells and Mankiewicz won the Oscar for screenplay (although it was nominated in 9 categories, but the film only won the only one), the award itself is the culmination of a series of painful disputes, and this is just this One of the many problems raised by the film: Mankiewicz’s contract with Wells clearly refused to give him the right to sign, but Mankiewicz’s career is in desperate need of stimulation, and he wants to get this award-through media and The struggle behind the scenes finally succeeded in winning the award. Today, however, Wells is still a legend, and Mankiewicz, who died in 1953, is unknown to everyone except the most observant fans.

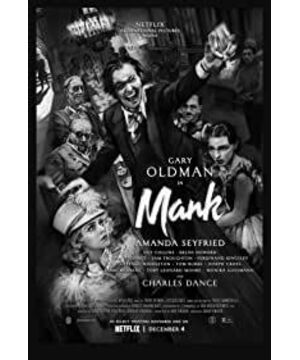

With the release of David Fincher’s new film "Mank", this situation should change. This biographical film based on the screenwriter’s years in Hollywood uses Mankiewicz’s role in "Citizen Kane". Centered on the work in Finch, it was adapted from the script of Finch's late father Jack, a reporter who Finch suggested to him. As Vinci said in a recent interview with Vulture, this film is an attempt to define the truth about Mankiewicz’s contribution to "Citizen Kane" and to the history of film-and dramatize his work in order to obtain a signature. Struggle.

Finch said his father's script manuscript closely followed the arguments in the most famous-and probably the most controversial-in the history of "The New Yorker". "The Way to Cultivate Kane", in 1971, was written by Pauline Kyle, one of the magazine's film critics at the time. This article was published in two parts, with a length of 50,000 words, trying to show that Mankiewicz should not receive only half of the credit for the "Citizen Kane" script, but the only credit. "Mank" closely revolves around Mankiewicz's behind-the-scenes social life and studio life in the 1830s, as well as his connection with the screenwriter behind his "Citizen Kane". To have a more complete understanding of Mankiewicz’s legacy, it’s worth re-examining his path of film creation. He has never respected film as an art form, and Kyle ignited it with "The Road to Kane’s Cultivation" In this struggle, in this battle, she is far from merely outlining Mankiewicz’s key role in "Citizen Kane" and his charming and tragic role. She tried to mislead Mankiewicz as a company. The villain was elevated above the independent artist Wells.

Mankiewicz was already a member of the Algonquin Roundtable. At the end of 1924, Harold Rose, on the eve of the launch of a new magazine "The New Yorker", asked him to be his first drama critic. . Mankiewicz was twenty-seven years old. Although he was not very young, he was very experienced. Born in New York in 1897 and raised in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, he was the son of German Jewish immigrants; his father was a poor but hard-working (and eventually recognized by the public) scholar, he was a harsh and harsh Character, he taught Herman the standards of high IQ, and Herman met these standards brilliantly, but was unhappy. Herman graduated from high school at the age of fourteen and entered Columbia University at the age of 15. With his new wife Sarah, he went to Germany in 1920. There, he quickly established his name and made his legend. As a reckless and wild wise man, he was able to persuade himself to devote himself to work and situations that would normally no longer be possible. After returning to New York, in 1922, he became a drama critic for The Times, and at the same time aspired to become a playwright, but with little success. When he joined the "New Yorker", Rose hoped that he could also win over his Algonquin colleagues; when everyone else objected, Mankiewicz offered Rose a noteworthy consolation: "Three heads have competed Zhuge Liang."

After working in The New Yorker for less than a year, the first issue of The New Yorker was published in February 1925, and Mankiewicz received a generous invitation to write in Hollywood. He needs a quick salary, not only to help support his family (he and Sara have two young sons), but also to pay off gambling debts. But he has no interest in movies, let alone dismissive. According to Sydney Ladenson Stern in the book "The Mankiewicz Brothers" published in 2019, he told his son Tang: "You can't have screenwriting literature, because it will be like comic literature." However, he is very good at it. For silent films, he uses his obvious wit to create subtitles, dialogues, and descriptive paragraphs. These paragraphs need to be short enough to adapt to the reading speed on the screen. With his news sensitivity, he can both Identify a good story and put it into a rigid format. He sent a telegram to his friend reporter Ben Hecht at the end of 1926, perhaps the most famous and perhaps the most influential telegram from Hollywood, offering him a job and decisively The sentence ends. "Millions of dollars will be robbed here, and your only competitor is an idiot. Don't let this pass."

Mankiewicz doesn't want to stay in Hollywood for long. Before heading to the west, he had made arrangements with Rose so that when he came back there would still be jobs waiting for him-or so he thought. In February 1926, Rose was disappointed with Mankiewicz's work habits and his job, and fired him via telegram, and Mankiewicz decided to continue working in Hollywood with no other choice. However, Mankiewicz not only dismissed the film, but also found that the nature of the film’s collaboration and the nature of the company’s work was incompatible with his writing philosophy; "The producer said to you,'Now in the third volume, this guy doesn’t The girl should be kissed, he should kiss the cow'. Then the whole picture is over, you can't bear it." At MGM, the process of industrialization is not so much a screenwriter room, as it is an exquisite corpse game; just like Irene. As Selznick (the daughter of the studio’s director Louis B. Meyer and the first wife of the producer David O. Selznick) explained, "Sometimes one screenwriter does the outline, and the others Make the outline, some make the dialogue, some make the revision, some make the complete rewrite."

Working for Wells is completely different-it gave Mankiewicz the first opportunity to create a film without a studio. His role in "Citizen Kane" is the result of some weird turns of fate: Wells originally hired him to write for radio shows, and plans to produce his first film for RKO, adapted from "Heart of Darkness." . Wells intends to play Marlowe and Kurtz at the same time, as he did in the radio version of the novel, his artistic conception is as extreme as everything in Citizen Kane. Marlowe will never be seen, because the camera will follow the explorer's subjective perspective all the way. This plan failed because of budget problems, and his next project, a puzzle about the American fascist conspiracy, asked Mankiewicz for help, but also failed. Then, in a conversation with Mankiewicz, he thought of a life about a powerful person, looking at the project from multiple angles. Wells and Mankiewicz discussed several possible themes (including gang boss John Dillinger), and Mankiewicz suggested newspaper tycoon and politician William Randolph Hirst. Mankiewicz knew Hirst well—before he got tired of Hirst’s enthusiasm, he and his wife had been regular visitors to Hirst’s huge St. Simon’s compound, just like him and almost everyone.

The collaboration between Mankiewicz and Wells on the screenplay-which Mankiewicz originally called "The American" (the final title was chosen by the head of RKO George Shaffer)-is a peculiar one Cooperation. Mankiewicz had severely broken his leg (he was a passenger) in a car accident and was in a half-length cast. Wells placed him in a house in Victorville, a remote town eighty miles from Hollywood, and was taken care of by a nurse. Wells' assistant, John Hausman, was present to tell the story at Mankiewicz's insistence. Secretary Rita Alexander typed out Mankiewicz’s dictation. Wells visited regularly and frequently called for inquiries.

In the summer of 1940, while the film was still being produced, the controversy over attribution began, and sorting out the details was like sneaking into the report of the Warren Committee. Mankiewicz realized that the result of the script was very good, and he regretted that the previous agreement with Wells stipulated that he would not receive any credit. Hecht and others in his circle persuaded him to make the matter public and win the only credit. For Wells, this will be a big problem, especially because losing the writer's signature may cause him to violate his contract with RKO, which stipulates that he will star, write, produce and direct. Mankiewicz appealed to the Screen Writers Association and then withdrew the appeal for fear of Hirst's revenge. In the end, RKO decided to grant him and Wells a joint signature. Quite famously, when the Oscars were announced at the awards ceremony, the cheers at the mention of Mankiewicz's name obscured the name of the second co-screenwriter, Wells. Neither person attended the awards ceremony, but Richard Merriman quoted Mankiewicz in his seminal 1978 biography "Mank" in a speech he said he would give. "I am very happy to accept this award in the absence of Mr. Wells, because the script was written in the absence of Mr. Wells."

The story of Wells and Mankiewicz’s collaboration is the perfect container for Pauline Kyle as a critic. She became famous with an article in 1963, "Circle and Square", attacking film critic Andrew Sarris and other supporters of "director theory", which emphasized the primacy of the director as the creative force of film. As a fan of Hollywood classic films and their commercial and popular appeal, she believes that the emphasis on directors has caused film critics to ignore the inherent collaboration of Hollywood film production. The director’s principled concern is portrayed as an orthodoxy that needs to be dismantled. In "The Road to Cultivation of Kane", she believes that many of the great things about "Citizen Kane" were not produced by Wells, but by the contributions of Mankiewicz and other actors and staff. Greatness is not produced by the originality of the film, but by its position in the film tradition and reflection on the film tradition, which are conveyed through the studio system and veterans. After "Citizen Kane," Kyle concluded that Wells was "alone, trying to be'Orson Wells', even though'Orson Wells' once represented a group of activities."

When "The Way of Kane Cultivation" was published, this article angered Wells himself-he was busy creating films, including "The Other Side of the Wind", and was watching all the critics and understanding of Wells's works. There was a strong response among historians with more complete stories. In October 1972, in the "Mr. Fashion" magazine, film producer Peter Bogdanovic used his own 4D article entitled "Kane Mutiny" to refute Kyle's discovery. Bogdanovic stated in the article that when reporting on her article, Kyle did not talk to Wells or anyone who has worked with him on the script, or to anyone who might offer a different perspective. Bogdanovic interviewed the screenwriter Charles Lederer, a close friend of Mankiewicz, and he said that Mankiewicz complained to him about Wells' many changes to the script. After Wells’ secretary at the time, Catherine Trosper, heard of Wells’s allegations that he had no contribution to the screenwriter of "Citizen Kane", he said to Bogdanovic: "Then I want to know that I always work for Will. What are those things Mr. Si hit!" Among other sources that Bogdanovic talked to, there was also a professor at UCLA, Howard Suber, who claimed that Kyle had coaxed him-promised him A book contract, but it was never realized-asked him to share with her a lot of his research on "Citizen Kane", but used these studies in her article without specifying the source, and at the same time distort the research results- — "After months of investigation, I think the screenwriter status of "Citizen Kane" is a very unresolved issue," he said. Bogdanovic wrote in 1998 that although he did "all the errands, research, and interviews" for this report, Wells himself-a close friend and colleague-was "revising and Played a powerful role in the rewriting." In a recent email, Bogdanovic said that there are "some fragments that Orson added or subtracted-mainly added").

Subsequently, more fair and more critical information about Mankiewicz's life appeared. It is worth mentioning that in 1985, scholar Robert Kalinger published an academic book on "Citizen Kane", which quoted newly acquired studio archives. Kalinger concluded that the script carries the work of the two screenwriters-Mankiewicz's work is fundamental, and Wells' modification is transformative. When Fincher was filming "Mank", he modified his father's script to weaken his anti-Wells tendency. The film he made is not interested in accusing Mankiewicz and Wells of the struggle, but instead explores the relationship between Mankiewicz and Hearst and how it influenced Mankiewicz’s creation of " "Citizen Kane".

So far, there is no doubt that the relationship between Mankiewicz and Hirst provided the basic material conditions for the film; at the same time, it almost ruined the film before it was released. Mankiewicz offered a copy of the script to Charles Lederer, a friend and screenwriter who also happened to be Hearst’s mistress and nephew of actress Marion Davies. It returned to Mankiewicz and marked the passage related to Hearst. Wells once denied that the film was adapted from Hirst's life, the studio has been strictly closed, and the script has not been seen by anyone outside the studio. But then, gossip columnist Heda Hopper pushed the door into the screening site and reported what she thought the film (more precisely, who it was). Hirst took action angrily and planned a campaign against it. The movie’s ugly publicity campaign, and the exercise of his considerable influence in Hollywood-especially on the head of MGM, Louis B. Meyer (he fired Mankiewicz in 1939)-to prevent The movie is shown.

The pressure Hirst exerts is terrible and deformed. He threatened to divulge obscene information about stars and studio executives, encouraged nativists to launch a campaign against European (mostly Jewish) film professionals who had fled Hitler and found jobs in Hollywood, and targeted (mostly Jewish) ) The head of the studio launched an anti-Semitic campaign. For this reason, Meyer (he is a Jewish) organized a consortium of directors of film companies, wanting to buy the negatives of "Citizen Kane" from RKO and destroy them, but Shafer, the head of RKO, refused their request. Hirst also let his newspaper follow Wells; he accused Wells of being a Communist (he is not); he used his influence on J. Edgar Hoover to get the FBI to investigate Wells Merriman wrote that Hirst’s film gossip columnist Luira Parsons contacted the local draft committee to try to enlist Wells. (Later, he also carried out severe press retaliation against Mankiewicz, exaggerating the minor accident caused by Mankiewicz driving under the influence of a national scandal). The movement worked: Although "Citizen Kane" was not burned down, Meyer asked the film companies, which also own the premiere cinemas in most major cities, to refuse to show it.

What saved "Citizen Kane" was the enthusiastic praise it received at private screenings when it was blocked. John O'Hara wrote in Newsweek that he "just watched a movie he thought must be the best movie he had ever seen"-and warned readers that they might never see it. On May 1, 1941, "Citizen Kane" was screened in a theater in New York, and was eventually screened nationwide; the film performed quite well in big cities, but it was a failed film—in fact, In the small town theaters where the film was booked, many of the films were not shown at all. Although the film earned Wells an instant reputation, its impact on his career was disastrous. Wells can no longer work in Hollywood as freely as before. In order to help Shaffer keep his job (this is because of the "Citizen Kane" controversy threatened, but also threatened the financial loss of Raidenhua), Wells re-talked about his second film "The Great Anba "Sun" contract, gave up the final editing rights, and paid the price-the film was dismembered by the film company, it cut forty-three minutes, and let another director remake the rewrite part. Wells said to Roy Fowler in 1946: "I came to Hollywood and said,'If they let me make a second movie, I'll be lucky.' They didn't. Since then, I have been He wanted to return to where he was when he first came, and take the contract to make a film in his own way, without interference." Since then, his only freedom is to use the money he earned as an actor to fund his films.

Before going to Hollywood, Wells described his work in the theater as an "actor-director", and he envisioned his movie production in the same way. In the theater, he always adapted Shakespeare, or Christopher Marlowe, or George Bernard Shaw, and when he made movies, he took a similar approach. He adapted Joseph Conrad, Shakespeare, Kafka, Booth Tarkington, several vulgar fiction stories, and even adapted a radio script involving the role of Harry Lime (he worked in Carroll · Reid played this role in the movie "The Third Man"). Why didn't he adapt Herman Mankiewicz into a movie? However, from a practical point of view, using the raw materials of contemporary people is also a competitor of honor in this industry (and the social hierarchies of Shakespeare and Wells are very distinct in one field). There is a difference. During the writing of "Citizen Kane", Mankiewicz used to call Wells a "watcher" and mocked his arrogance; Mankiewicz once saw Wells pass by in the studio and said: "Besides the grace of God, there is also God."

However, Wells' serious self-respect as an artist is, after all, one of the qualities that distinguishes him from the cynical and unsatisfactory Mankiewicz. Mankiewicz’s own evaluation of the art of screenwriting is too harsh (it is indeed an art compared to comic books), but he is correct that screenwriting is a less important activity than writing plays — not because the meaning of movies is not as good as Drama, but because the work of the screenwriter is an industry need rather than an artistic impulse. Kyle’s most serious mistake in her controversy is that he did not realize that if there were no Mankiewicz, Wells would still be Wells; if he could make "Heart of Darkness", it would probably look like "Citizen Kane" is equally original, and free of Hirst's vengeance, he is likely to make a second film without losing his creative freedom. In this regard, without the constraints of Hollywood, Mankiewicz is likely to reach his creative height earlier and longer. The story of Mankiewicz's film career is no less than that of Wells, involving the horror contained in Hollywood's glory-the ruthless power of commercial institutions imposing their practices and formulas on film art.

Mankiewicz performed better in the short term after "Citizen Kane" came out. After the film came out-he won the Oscar at Mankiewicz-his career improved. His most outstanding film is "The Pride of Yankees," a 1942 Lu Glick biographical film. Another great film he wrote is "Christmas Holiday" in 1944, a noir film starring Deanna Durbin and Gene Kelly. It is characterized by a complex flashback structure, similar to "Citizen Kane", which is composed of Directed by Robert Siodmak, he is one of the great film noir experts (and one of the European Jewish filmmakers who fled the Nazi regime), and the film itself is excellent. However, Mankiewicz's bad habits stopped him; he was only intermittently reliable, and his health began to fail. As Merriman reported, Hollywood during the war and after the war has also become the home of a new generation of executives and producers. For them, the roots of Mankiewicz’s roundtable and news turmoil are more of a kind. Weird nostalgia, not unquestioned admiration. Merriman wrote that Mankiewicz was very clear about the fact that he had done film work and suffered only because of good pay. "I have only been here for a few months. I don't know what happened. You started to work in a job you don't like. Before you realize it, you are already an old man." Although Mankiewicz is left in the history of film Has an indelible mark, but he has been hindered from the beginning by his contempt for the film and the contempt for the studio machinery that determines the way the film is The things praised in the strange defense. In the end, Mankiewicz was cursed because he didn't regard film as an art at all, and Wells had achieved greater success because he had never regarded film as anything.

About the original author:

Richard Brody began writing for The New Yorker in 1999. He writes about movies in his blog "Watching Movies in the Front Row". He is the title of "Movie is Everything: Jean-Luc." Author of "Godard's Career".

Original link:

Herman Mankiewicz, Pauline Kael, and the Battle Over “Citizen Kane”

View more about Mank reviews