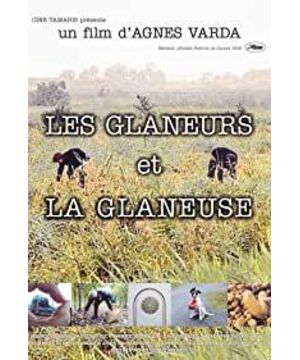

(Four stars out of 10) In the alley, we saw people hunting for treasure in the rubbish heap. The Gleaners place them in an ancient legend. The practice of scavenging has been protected by the French constitution since Henry IV established the right to scavenge in 1554, and the men and women who scavenge the trash cans and markets of Paris today are the gleanings of Miller and Van Gogh. (Note: It is the same English word as "scavenger") descendants. Scavengers usually follow the harvest season, picking up what was missed in the first harvest. In Agnès Varda's thoughtful new film, we see them in potato fields and orchards, where farmers actually welcome them (the first pickers missed tons of apples because Professionals work quickly and do not have the patience to find hidden fruit). Then we see the city's scavengers, an artist looking for items to make into sculptures, and a man who hasn't paid for food in over 10 years. Everyone seems to know that the practice is protected by law, but no one seems to be fully aware of what the law is about. Varda photographed jurists standing in fields, wearing robes and holding codexes, saying that scavenging must be done between sunrise and sunset. Varda also showed oyster pickers in rubber boots who said they couldn't get too close to the oyster beds or pick too many oysters. In a provincial capital, Varda pondered a case of young unemployed. The supermarket manager poured bleach into the trash can to stop them from scavenging, before they knocked over the trash. Perhaps both sides have broken the law; young people have the right to scavenge, but not to destroy public property. But when Varda talked to the young homeless people in the square, we realized that they didn't have the spirit of other scavengers, they just wanted to do bad things with impunity, not to exercise their rights. Although French law considers scavenging a useful profession, they have turned themselves into criminals. In Varda's eyes, the real scavenger is a little noble, a little idealistic, a little stubborn and very frugal. We meet a man who is picking up food and looking for things to sell, and we follow him back to the suburban homeless shelter where he has taught literature classes every night for years. Varda and her photographer also discovered a clock with no hands – worthless until she placed it between two stone cat cats in her home, which took on a strikingly simple form. Of course Varda herself is a scavenger. She picks up scavengers. In this documentary-like film, she hides a tender reflection on her own life and life itself. The house itself where she and her husband Jacques Demy lived It has a scavenging spirit: it's not a luxury apartment, but an old garage with lots of compartments and rooms around a central courtyard. One of them is the kitchen, one is Jacques' office, one is the room of his son Matthew, one is Varda's studio and so on. Varda, now 72, made her first film when she was 26. She is the only female director of the French New Wave and is more committed to the New Wave spirit than many male directors. In The Gleaners, she has a new tool—a modern digital camera. We can feel her joy. She can hold it in her hand and carry it with her. She got rid of the bulky equipment. "Shooting one hand with the other," she said excitedly while doing it. She shows how the new camera enables the filmmaker's personal short films - how she can go out into the world without risking a huge budget and simply collect images like a scavenger collects apples and potatoes. As the narrator, she confided to us at one point: "My hair and my hands keep reminding me that my time is running out." She told her friend Howie Moffshowitz, a Boulder, Colorado, of critics, saying she had to film and narrate some scenes on her own because they were so personal. In 1993 she directed Jacques Demy of Nantes, the story of her late husband, and now it is her own story: a woman whose life is to travel with her camera The world, looking for something precious. Said she had to film and narrate some scenes on her own because they were so personal. In 1993 she directed Jacques Demy of Nantes, the story of her late husband, and now it is her own story: a woman whose life is to travel with her camera The world, looking for something precious. Said she had to film and narrate some scenes on her own because they were so personal. In 1993 she directed Jacques Demy of Nantes, the story of her late husband, and now it is her own story: a woman whose life is to travel with her camera The world, looking for something precious.

View more about The Gleaners & I reviews