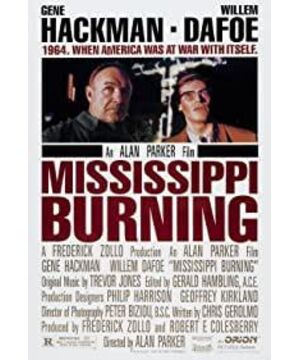

★★★★ (Four-star full score) Movies often take place in small towns, but they rarely seem to live there. Alan Parker's "Blood Storm" feels like a movie from the inside out. It is so familiar with the customs of the southern town, that after reading it, I know where to drink coffee and where I should avoid it. This strong sense of time and place—the Mississippi countryside in 1964—is the lifeblood of this movie. Compared with other movies I have seen, this movie shows more deeply the hatred of American races. Based on a true story, the film tells the disappearance of three young civil rights workers, Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner, who were part of the Mississippi voter registration movement. When their bodies were discovered, their bodies became irrefutable evidence by officials who complained that the whole case was just a propaganda stunt made up by northern liberals and outside instigators. This case became one of the milestones, just like the day Rosa Parks took her seat on the bus. Movement), or like the day Martin Luther King entered Montgomery, on the long march towards racial equality in this country. But "Blood Storm" is not a documentary, it does not deliberately present a story based on facts. This is a real police drama, bloody, fanatical, and sometimes unexpectedly interesting. It tells the story of two FBI commanding and investigating the disappearance. No one can be more antagonistic than them: Anderson (played by Gene Hackman), a kind old boy who used to be a sheriff in other towns, and Ward (played by William Dafoe), one from the judiciary Smart young guy. Anderson believes that we should keep a low profile, he wandered around the barbershop looking for the suspect. Ward believes that force should be used to summon hundreds of federal agents and even the National Guard to find the missing. Anderson and Ward don't like each other very much. They all believe that they should be responsible for directing this operation. When they parted ways, we met some people in the small town. The cunning mayor who opposes outsiders who incite violence, the sheriff who thinks he can threaten the FBI, and Pell (Brad Doliff), a thief-eyed deputy who has an alibi when three of them disappeared , And it is a good alibi-but why did he have such a good alibi at that time? Unless he needs it. This alibi depends on Pell’s wife (Francis McDomond (Played), and she has endured this self-blaming racist for many years. Anderson, played by Hackman, immediately singled her out as the key person in the case. He believes that the sheriff’s department handed over the three people to the local Ku Klux Klan, and the Ku Klux Klan killed them. If he can let the wife speak, the enemy's entire house of cards (note: the shaky organization) will collapse.

So he started wandering around and chatting. Moved his feet like a shy boy in her living room. He gradually weakened his voice so that in the silence she could imagine how beautiful he was about to say she was. But Anderson played with her like a piano. She also wants to be played with. Because Hackman is such a silent actor, it will take us a while to realize that he is really in love with her. He wanted to rescue her from the scumbag, and then hold her in his arms. This relationship is in contrast to the main line of the film, which tells about excellent police work, interrogations, searches, and-mainly-the hope for insider information. We have reason to believe that the local black residents knew who the murderer was, but the Ku Klux Klan burned down the house of the boy who might confess, and the black residential area was shrouded in terror. Director Parker did not use melodrama to express the fear of local blacks of revenge; instead, he used realism. We see what it will be like if you don't be a "good nigger". In a segregated fast food restaurant, Ward approached a black man and asked him some questions. The black man refused to talk to him, but was still beaten by the KKK. Sometimes it may be common sense to remain silent. Parker’s previous work involved intimidating bullies, the most obvious of which was "Midnight Express," but the special thing about this movie is his understatement of evil. There are no villains and sadisms in the movie, only ordinary, evil racists. At the end of the movie, the body and the murderer have been found, and the wheels of justice have begun to roll. We already knew the outcome of the case when we walked into the theater. What we may have forgotten or never know is what kind of thought prevailed in 1964. The civil rights movement in the early 1960s was the most glorious moment in modern American history, because at that painful moment, we were determined to improve ourselves, not others. We have grown, the South has grown, and the entire country has grown. We are more able to identify with this radical idea: all are born equal and are given inalienable rights, including life, freedom, and the right to pursue happiness. "Blood Storm" can evoke more clearly than other films how we used to deprive blacks of their rights legally, especially in the South. In the early years, most of the United States was a totalitarian area, where the criminals were all blacks. The situation of black people today is not particularly good, but at least there is no longer official racism in the law books. I have never seen a movie that captures the appearance, feeling and smell of racism so powerfully. In this movie, we can feel how charming hatred is to racists and how it replaces other forms of entertainment, How to make up for their sense of worthlessness. When the main part of racism is broken, we will feel free from the shackles and fresh air will flow in. "Storm of Blood" was the best American movie of 1988, and it may also be a candidate for the best film Oscar. Putting aside the pure entertainment value-this is the best American crime film in years-this is an important statement about an era environment that should not be forgotten. Oscars like to award awards to famous movies in which crimes long ago are corrected in distant places. Below are some of my predictions for the nomination. The two leading actors-Hackman and Dafoe-may have Oscar nominations, but I hope everyone will pay attention to McDomond (Note: Later Hackman nominated the best actor, McDomond nominated the most Beautiful girl), she could show off her skills, but chose to show us this woman: she was raised, trained, and beaten to become her husband’s servant. In the end, she rejected such a role because she saw her like her. It is wrong for the husband to treat black people like that. McDomond’s performance was quiet, shy and fearful, but in the moral choices she made, she replaced a generation, and they finally said: Hey, what happened here is not fair at all.

View more about Mississippi Burning reviews