one

When I was a child, I once heard adults tell stories about "sending death in a kiln", that is, in a very long time ago, people would send the elderly over 70 years old into the "cavern cave" on the mountain, without giving them food. Eat and let them starve to death. This is because the state officials at the time believed that the elderly were useless when they were old, and they only had to eat and not work. By allowing them to die after reaching a certain age, they could save the material burden of the people, so there was such a decree. But there was a dutiful son in the village who hid his old mother, who had reached the age of 70, in his sweet potato cellar, secretly feeding her, falsely claiming that his mother was swept away during the flood. Later, a strange mouse came to the middle school, with horns on its head and a weight of 100 catties. The dutiful son told his mother about what happened outside. The mother said, you need to keep a cat of 9.5 jin and put it in your arm cage. If you encounter the rat that makes trouble, let the cat out, so that you can be cured. Rat plague. But it's hard to find a cat that weighs nine and a half pounds. His mother taught him to give cats the meat that people are not willing to eat, so he raised a cat that weighed nine and a half pounds. Just when the horned mouse reappeared and walked through the walls and was lawless, the dutiful son opened his sleeve cage, the cat jumped out with a swoosh, and caught the mouse. The emperor wanted to admire this dutiful son, but he confessed the truth to him, saying that his strategy was learned from his elderly mother, who is 71 years old this year. The emperor realized that even old people are useful, and since then abolished the custom. This story is just one version of the many "dead kiln" stories that circulated in the Han River valley where I grew up. From Gucheng onwards, it is far away from the Huxiang Plain and enters the Hanshui Valley between the Qinba Mountains. My family is located in the Yunyang area in the middle and upper reaches of the Han River. Until the Tang Dynasty, the mountainous areas there remained the alienation of the empire. Although it was only 500 miles away from Xi’an (Chang’an at that time), Fangxian (Fangling) there was the exile of Tang Zhongzong, Li Xian and others. To this day, there are still illiterate farmers and peasants who sing songs similar to the Book of Songs. of folk songs. In the 1960s, because of its topographical features and its location in the heart of China, it gained national defense strategic considerations and developed a heavy industry with the Second Automobile as its core in a short period of time. But until 2016, there was no airport in this place with the skull fossils of "Yunxian people", the Taoist cultural heritage of Wudang Mountain, and the Danjiangkou Reservoir; as of today, there is no high-speed rail connected to it. Not only that, but it is also on the north-south dividing line of Chinese human geography. People eat wheat. Planting rice again and speaking the "Southwest Mandarin" of Yunyang area, in the gap between Hubei, Henan, Shaanxi and Chongqing, it is difficult for us to define our own belonging, although identity itself is an issue of no urgency to us. It is this multiple back-and-forth relationship between center-periphery, industry-agriculture, open-closed, modern-premodern that made me pay attention to the interaction and continuous development of cultures of different eras on this land from a very early age. . Sometimes it even reminds me of The Heartland by Brazilian author Cunha. Yes, this land lies in a sometimes forgotten fold of our vast homeland, which in some ways has yet to be written. It is in this "fold" that the legend of "Death Kiln" was born and continues to circulate.

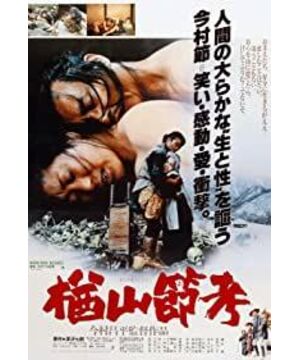

So when I saw Shohei Imamura's film "Narayama Festival Kao" for the first time and knew that there are similar legends of abandoning the old in far-off Japan, I had a shock that was hard to let go of. It resonated with me for a long time to forget. I first watched Shohei Imamura's 1983 version of "Narayama Festival Kao", and then I was attracted by this theme, and I watched Keisuke Kinoshita's 1958 film of the same name. I also found the short story "Narayama Minor Exam" by the Japanese "postwar school" writer Shichiro Fukasawa, which is the common blueprint for the two films. Before "Narayama Minor Test", there was a famous Japanese book "Musheshan", which is also a story about abandoning the old. The background is the Japanese Warring States Period in the late 16th century. This is not the original source. In the "Anthology of Ancient and Modern Japanese Songs", there is "My heart is difficult to calm down, seeing this more advanced abandoned old mountain, under the shroud of moonlight", it is about a filial son who turned his back on his old mother to abandon him Mountain, but could not bear to abandon it. This song was later turned into a story in "Yamato Story" and "The Story of the Past and Present". In the thirtieth volume of "The Story of the Present and the Past", there is "The Aunt of the Shinano Country Abandoned Mountain".

two

The first thing I think about the film style of "Kai Jinhei" is the naturalism that hovers on the horizon of modern Japanese literature, but he seems to be self-taught when it comes to paying attention to the lower classes of society and people's animal desires. In his autobiography, I hardly read any reference to his connection with that trend of literary thought that has passed the limelight, and his favorite writers, such as Ibushi Ibushi, only vaguely revealed some influences that did not constitute a decisive factor. Imamura suffered from low self-esteem all his life because he was born in the city when he was a teenager. He believed that "only in the countryside can there be real people and life." He later made a fortune selling alcohol and tobacco on the black market briefly; although he won the Palme d'Or twice, he repeatedly came to the brink of bankruptcy for making films. The novel on which "Narayama Festival Kao" is based is narrated by Fukasawa Shichiro in the tone of a folk tale that does not leave axe marks. The whole story minimizes the traces of the recorder's processing, and retains a large number of local dialects and oral expressions. It can only be assumed that a love of indigenous culture, folklore, and the facts themselves naturally leads Imamura's lens toward naturalism. Regarding the relationship between Imamura and Yasujiro Ozu, the first impression I got from second-hand sources was considered to be biased. After reading the passages about Ozu in his memoir "The Grass Grows Crazy", I found that although Gui Imahira disagreed with Ozu's aesthetic style and shooting method, the two did not reach the point of incompatibility. And learned a lot from the harshness of self-style. "Even if he just chooses the camera position, he insists on finding the most suitable place according to his own aesthetic consciousness, and once he chooses a satisfactory position, he will never change it. I occasionally think in my heart: this is how the director should be. His kind of I keep the spirit in my heart.” Ozu also appreciated Imamura, and Imamura recalled: “Although I left because I was against the way Ozu’s crew filmed, director Ozu seems to have always cared about me very much.” He greeted Imamura Shohei's wife Akiko to deliver the documents, and took the opportunity to meet her. Imamura guessed that Ozu might be out of curiosity and wanted to know what kind of woman he was marrying. These details finally answered some of my confusions about the relationship between Imamura and Ozu during their collaboration. In fact, "depicting maggots will end in death" is an extremely exaggerated statement. Imamura's films are vulgar and at the same time do not give up strange innocence. Barbaric customs that are hard to restrain, nor do they shy away from praising their strong and optimistic life instincts. His women, for example, are often confused, clumsy but plump, fertile, and maternal. On the one hand, Lingpo in "Narayama Festival Kao" taught her daughter-in-law Ayu, whom she recognized, the skills of fishing, and on the other hand, she Through a small trick, she successfully used a public incident to bury her granddaughter-in-law, the eldest daughter of the Yuwu family, Asong. When faced with the inevitable death of a 70-year-old, she was frank and fearless. She carefully prepared for the banquet before going up the mountain, and quietly knocked out her mouth full of good teeth in a self-tortured way, and insisted that her son Chenping would send her to her. To the end of Narayama, behind this sacrifice is her indirect acknowledgment of the right to life that her heirs deserve. Imamura is clearly aware that he has more to say than director Kinoshita's 1958 version of "Narayama Festival Kao". "I watched this movie when I was young and thought it was very interesting, but I felt that the director Kinoshita was ultimately trying to emphasize that this is a completely fictional story. He believed that abandoning one's parents was something that was never allowed to be done. , The bangko sound of Kabuki was added at the end, probably to deliberately emphasize the fictionality of the story." Imamura made his 1983 remake of the story infinitely closer to reality, but at the beginning and end of the story, he still couldn't avoid the ambiguity. The use of a sexual curtain, the snow scene, acts as a box that closes the eye, temporarily suspending the viewer's disbelief over the main part of the bizarre story. The snow scene implies that all the absurd plots take place in a remote and unattended village, where the mountains are covered by heavy snow in winter, almost isolated from the world, and even the unnatural phenomenon of rats eating snakes occurs. Only in this extremely closed environment can the extreme poverty of human tribes and the reversal of the ethical order be envisaged. Imamura moved the story to after the introduction of guns (Tatsupei, who was only 15 years old, killed his father with a shotgun on a whim), but technological innovation has not shaken people's worship of the mountain god, nor disturbed the stability of their social structure. In 1968's "The Desire of the Gods", the story also takes place on a closed and primitive island. By placing the ancient social community in front of the harsh and eccentric laws of nature, he tries to examine some hidden reality of reality. dimension. As Imamura himself said, Japan has not changed for thousands of years. He is not concerned with the direct projection of ideology and politics, on the contrary, he believes that the examination of primitive folklore is a more effective way to understand the deep texture of Japanese contemporary society. Part of the reason why Imamura's heterotopia creates a strong sense of substitution lies in the extreme realism of its methods. In the 1970s, he had a long documentary period, participating in the investigation of Japanese soldiers who did not return home after the war but stranded in Southeast Asia, and also investigated serial murderers, low-level prostitutes, people who disappeared inexplicably... In other words—— Those "abandoned people", from these entrances, he found a way to understand the Japanese psychology during the great transition period after the war. He believes that relying on people The lower part of the body and the lower layers of the social structure are the realities of Japanese daily life that can tenaciously support themselves. In his films, there is a sense of non-intervention that "heaven and earth are not benevolent, and all things are dogs". So he uses the overhead shot many times, always placing his characters in the interrelationships and analogies with animals and plants. In his films you feel a turbulent flow of life, surging forward in the midst of established conventions, riots and repression. No matter how stubborn, blind, heartless, and forgetful a person is, he will always find a reason to survive.

View more about The Ballad of Narayama reviews