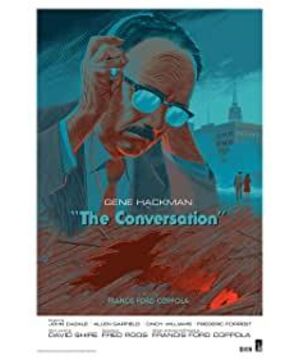

Basically, I have seen the most complete parable of modernity, from the modern occupation of prying into the lives of others-to becoming a major player in the industry, losing the subjectivity of oneself, breaking up the family and being unable to obtain intimacy, resulting in a sense of nihility-and then to hope. The intervention of the other (perceptual sympathizer) life to achieve the counter-evidence of self-emptiness and regain subjectivity. Then the occupation failed, it was just another person’s obscenity-in the end, in the defense of the little security left, even the last faith was lost, the house was ruined, the space was lost, and only a little fragment of modernity was left. pastime.

The selection of several narrative symbols has indeed been greatly affected by magnification. They all started from the questioning of instrumental rationality (photography/recording), women without physical performances, and other roles still obsessed with material beliefs. The highlight is the beautiful spy telephoto lens, the bright and dark depth-of-field lens, the wind and crumbling things (Bertolucci-like atmosphere) of the replay, and the daytime scene where the shadow of the building casts long shadows. The overall narrative is much more logical than magnification, and the main line is clear and strictly follows the structure of Hollywood dramas. And the time is concentrated, the discussion of topics is almost evenly spread in every scene, and the rhythm is well controlled. Religious imagery points to the dissolution of the sense of sacredness after prying into privacy. The precise selection of the lens has a style of flat composition. Sure enough, the best quality modern movies, whether Eastern or Western, are already trying to get rid of the limitations of perspective.

View more about The Conversation reviews