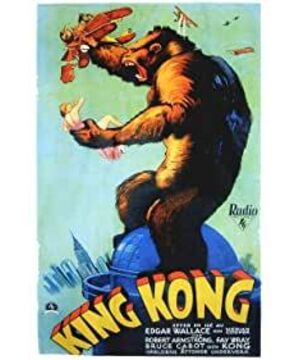

A killer monster talkie that ushers in an era of creatively cranking out disproportionate behemoths to treat cinema audience with thrills and chills, the original KING KONG is the irrefutable forefather, most extraordinarily for its cutting-edge stop-motion animation technique, under the dexterous hands of Willis O'Brien, which intricately melds with rear projection, matte painting and animatronics to knock its spectators dead, who are bestowed with an unprecedented vicarious experience of beholding a gargantuan gorilla-like monster, rampaging over, first an island jungle, a tribal village, then NYC, topping off by surmounting the pinnacle of the Empire State Building (the world's tallest building at that time), before its fateful destiny precipitated by the weaponry of modern civilization.

Depression-era USA, from New York Harbor to the uncharted Skill Island, filmmaker Carl Denham (Armstrong), embarks his treacherous journey after recruiting a strapped but comely young girl Ann Darrow (Wray) as his new picture's leading lady in the eleventh hour, only revealing his destination later on, the mystique of an apocryphal creature has been honed up to the hilt, with Ann feigning her trademark scream when sees something unspeakably horrendous, which will soon come out without any scintilla of feigning after she is served as a human offering by the local tribe on the island as “the bride of Kong”, and being tossed around like a toy (and incredibly unscathed) by the ape-monster that seems to take a particular shine to her.

It goes without saying that the special effects inexorably look rather dated to today's eyes (86 years on), Kong's image is more mechanic and cartoon-like than realistic, and a further emotional interrelation between the beauty and the beast becomes stone-cold impossible, but for a cinephile, our admiration and reverence towards the teamwork behind the arduous job of contriving such an enterprise is profound. In retrospect, KING KONG also benefits from its pre-Code temporality, that the film doesn't shy away from Kong's feral, human-chomping-and-stomping ferocity.

Kong's violence might be excessive, but compared to the human team's wanton reaction of disposing a stegosaurus (unwittingly betrays those adventurers' own savage instinct), not to mention their reckless action that obliquely brings ruination to the tribe, which has been maintaining a non- aggressive cohabitation with Kong and the Jurassic living fossils, Kong's fascination of Ann is perversely much more human and affecting (any sexual innuendo is punctiliously fudged), in the sense that his protective inclination towards that dainty, screeching creature is something unadulteratedly congenital and inexplicable ( he battles with three different pre-historic monsters to save Ann out of harm's way), which leaves his denouement a resounding pang in a viewer's heart. Meantime,what now looks jarring is the ethnocentric idea that a white girl is being lionized by a foreign tribe as something exotically superior than their own skin, and the white men's rough trespassing on their turfs only makes the aftertaste smack of racial insensitivity.

The long and the short of it, like its preternatural protagonist, Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack's KING KONG itself is almost, too big to fall, remains as a landmark Hollywood commodity that pioneers in configuring a fantasy world of horror, excitement and otherworldliness, that has been still hogging the market and incessantly piquing our innate interest.

referential entries: Peter Jackson's KING KONG (2005, 7.0/10); Karel Zeman's THE DEADLY INVENTION (1958, 6.5/10)

View more about King Kong reviews