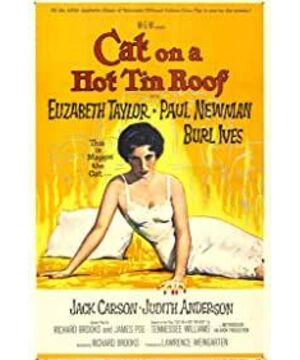

Damn the Hays Code, Tennessee Williams' Pulitzer-winning play is bowdlerized on its way from Broadway to the silver screen, where all its homosexual reference is tactlessly papered over. That said, riding on the strength of its top-line ensemble cast, Richard Brook's exquisite film adaptation still dazzles and hurtles upon a Southern family's trouble waters.

The crises of the Pollitt family, an affluent rags-to-riches Mississippi empire of cotton plantation built by the patriarch Harvey aka. Big Daddy (Ives, reprises his role from the stage), are multifarious: his youngest son Brick (Newman), a former athlete who abuses himself with alcohol and despondency in the wake of the suicide of his best friend Skipper, and doesn't want to have any physical intimacy with his sultry wife Maggie (Taylor); then their is the ominous dread of Big Daddy's doom, who is diagnosed with terminal cancer and has less than one year to live, but Dr. Baugh (Gates) fabricates a lie to appease him and his wife Ida aka. Big Mamma (Anderson), only the cat will finally get out of the bag, and its theme of dual courage (for Brick to face life and for Big Daddy,death) plays out with elemental emotional upheaval on the eve of Big Daddy's 65-year-old birthday, which occupies 99% of the time-frame and takes place entirely in their sumptuous family manor.

The nexus here is the raison d'être behind Brick's indifferent attitude and self-abandoning intemperance that puts himself against everyone else, since homosexuality is off the table, Brooks and James Poe's script has to scrape the bottom of the barrel and leaves it mostly to the rage of being (presumably) two-timed, when that proves to be not the case, the barrier causes Brick's connubial inaction naturally vanishes, ergo, that inconsolable guilt and grieve derived from losing a loved one in Williams' original play is pitifully deadened to conceive a perfectly heteronormative ending, with a dated, self-congratulatory whiff of natalism (especially grating after hammering home what kerfuffle a band of bratty, insolent kids can engender).

Doused in booze and whose mobility is impeded by a crutch, Newman is magnificent and passionately engaged from A to Z and rightfully receives his first Oscar nomination for a very difficult and complex role. Underneath his Adonis appearance, Newman unleashes Brick's harrowing obduracy to the hilt , he is self-centered enough to submerge himself entirely in his existential cynicism and doesn't give a damn about the whole world after what he suffers, not even his father's death knell, but deep down, he is merely a love-wanting child borne out of a poor rich boy's misery and destructively waging war on the mendacity of the world, a tour de force loaded with fiery explosion.

An Oscar-nominated Taylor, adorned only by two pieces of finery and a pearl choker, also utterly takes our breath away with her ineffable beauty, a refined southern belle locution and superbly lived-in performance, whenever she and Newman are on screen together, they are the perfect specimen of what divine human gorgeousness looks like, for that reason alone, the film should be included in any film buff's must-see list. Her Maggie is a valiant fighter, a can-doer, a go-getter, and her heart-stopping allure is fiendishly counterpoised by her super-fertile sister-in-law Mae (a plain-looking Sherwood), the wife of Brick's elder brother Cooper (Carson, walking a fine line between grasping and subservient), fanatically battling a losing game to earn affection from Big Daddy with all her pesky tailed assets,Williams' misogynistic partiality is quite revealing.

Performance extraordinaire suffuses the rest of the ensemble, in the co-leading role, Burl Ives' larger-than-life bravura as Big Daddy is equally impressive, delivering Williams' florid texts with resounding decibel, and brings about incredible gravitas and compassion in the third act when reconciliation shapes up during a barnstorming tête-à-tête between a befogging father and his prodigal son. Then there is the ever-forbidding Anderson, refuses to give Big Mamma a simple caricatural veneer, and finds her disparaged yet supportive wife a strong purchase in the catharsis-inducing chamber drama that is worthy of Williams' name, regardless of the compromises inflicted by an odious force majeure.

referential entries: Mike Nichols' WHO'S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF? (1966, 8.2/10); Martin Ritt's THE LONG, HOT SUMMER (1958, 6.3/10); Joseph L. Mankiewicz's SUDDENLY, LAST SUMMER (1959, 7.4/10) .

View more about Cat on a Hot Tin Roof reviews