The original text is taken from "THE DYNAMIC FRAME Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood" by Patrick Keating. When discussing the movie "Sunrise" in this book, it is based on the influence of German films on American movies in the mid-20s, and the attitude of American filmmakers to camera movement as trick shots: it is the specialty of funny comedy. Not in line with the elegance of serious drama. In the German films "Last Laugh" and "Vaggle Class", the camera movement and angle shocked American filmmakers. The contribution of these innovations is not only technical, but also cultural intervention. The mobile camera is no longer a funny trick, but an expression of artistic ambition. The opposition between static drama and dynamic comedy has also been broken.

The following is the original text:

Sunrise

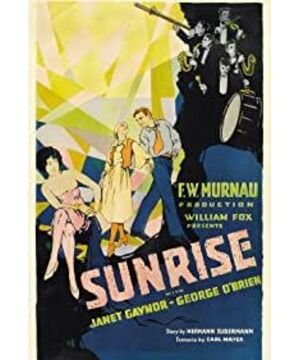

A great deal was riding on Sunrise—not just Fox's investment but also Hollywood's ever-evolving identity as an industry both American and international. Would Murnau assimilate to the American style, devising unusual angles to add “kick” to the story? Or would the German director continue to explore the semisubjective realm with a style that had inspired critics to reach for comparisons to Cezanne and Picasso? Murnau had promised to make a film with American virtues: speed, pep, initiative. The finished film belies this promise: Sunrise is slow and serious, with characters notably lacking in drive. The story is about a rural couple, simply called the Man and the Wife (George O'Brien and Janet Gaynor). The evil Woman from the City (Margaret Livingston) convinces the Man to kill his wife in a staged boating accident.He cannot go through with the murder, and, overcome with guilt, he follows his wife to the city, where he slowly regains her trust. Whereas many Hollywood films emphasize external action, the conflict here is almost entirely internal: the Man must rediscover his love for his wife, and the Wife must recognize that his conversion is sincere. This minimal plot leaves ample room for emotional expression.

To tell this tale, Murnau used almost every cinematic device available, from set design and acting to lighting and camera movement. As in The Last Laugh, Murnau explored the ambiguous territory of the semisubjective. In one celebrated seTuence, the Man walks through the marshes to visit with the Woman from the City. Cinematographers Rosher and Struss placed the camera on a platform suspended from tracks specially built into the studio's ceiling, using motors to aid the shot's operator, Struss, by lifting the camera platform up and down as it moved forward. 58 For all the shot's technical bravado, its real interest lies in its shifts from external to internal and back again. The camera starts out by following the Man from behind and then tracks with him in profile after he makes a turn to go through some trees (fig. 1.7a–b). Here,the mode is external but attached—we observe the Man from the outside, but we discover the space as he discovers it. When the Man approaches the lens (fig. 1.7c), the camera pans to the left and dollies forward, pushing through some branches to discover the Woman from the City (fig. 1.7d). 59 For a brief moment, it appears that the film has entered a subjective mode, representing what the Man sees through his own eyes. The Woman turns her head. Perhaps she will look directly at the camera, as if welcoming the Man's arrivalbut, no, her gaze crosses past the lens, and the bored look on her face indicates that the Man has not yet arrived. First attached and then subjective, the mode becomes nonsubjective and nonattached, showing an event that the Man cannot see yet. A moment later the Woman looks offscreen again,this time recognizing that the Man is approaching. When he enters the screen from off-left, it is a further perceptual surprise: the last time we saw him, he was off-right. The Man and the Woman kiss, and the shot comes to an end. In a lecture in 1928, Struss described this shot in terms that reflect its ambiguity. His statement, “Here we move with the man and his thoughts,” evoked a subjective interpretation of the image, but later he claimed, “ We seem to be surreptitiously watching the love scenes," as if the camera had adopted the perspective of an unseen observer. 60His statement, “Here we move with the man and his thoughts,” evoked a subjective interpretation of the image, but later he claimed, “We seem to be surreptitiously watching the love scenes,” as if the camera had adopted the perspective of an unseen observer. 60His statement, “Here we move with the man and his thoughts,” evoked a subjective interpretation of the image, but later he claimed, “We seem to be surreptitiously watching the love scenes,” as if the camera had adopted the perspective of an unseen observer. 60

Other shots extend this semisubjective approach. In The Last Laugh, Murnau had placed his camera on a rotating platform to create the effect of the world spinning around the porter. In Sunrise, Murnau designed an ingenious variation on this strategy, depicting the twists and turns of a trolley ride. The first part of the seTuence was photographed on a trolley path built alongside Lake Arrowhead; the rest was shot on another constructed line that circled into Rochus Gliese's enormous false-perspective city set on the Fox lot. 61 One shot shows the Wife huddling in the corner of the car. We can barely see her face, but the trolley veers right and then left, showing us tracks, a worker on a bicycle, a factory, and other images indicating that she is reaching the edge of the city (fig. 1.8a–b).The unpredictable swaying of the trolley expresses her emotional state—her terrified confusion about her husband's newly revealed capacity for violence and betrayal. Meanwhile, Murnau uses the trolley's movement to comment on the inevitability of modernity: these two peasants have no control over the trolley car , and they must stand by passively while the background changes from the countryside to the city, a change in landscape that will render their peasant lifestyle obsolete.a change in landscape that will render their peasant lifestyle obsolete.a change in landscape that will render their peasant lifestyle obsolete.

In her insightful analysis of the film, Caitlin McGrath has situated Murnau's shots within a longer tradition of camera movement stretching back to the cinema of attractions, as in Bitzer's subway film in 1904 (fig. 1.1). 62 Another proximate comparison is the trolley scene from girl Shy. There, the Boy treats the world as a series of obstacles to be overcome, commandeering a trolley car to get to his destination as Tuickly as possible. In Sunrise, the movement of the trolley does little to advance the goals of either character, who are merely passengers on a journey they cannot control. In one sense, girl Shy does a better job integrating story and shot: the action on the trolley serves to advance the protagonist's goal. In another sense, Sunrise is the more fully integrated of the two.girl Shy briefly abandons the Boy to deliver a gag about the drunkard's confusion. Sunrise lingers on the passage of the trolley because its swaying motions serve to express the Wife's state of mind. Every swerve is expressive.

The latter film further develops its characterization of the modern city in a pair of seTuences showing the couple crossing the dangerous street. In the first seTuence, the camera is on a dolly following the Wife (probably a stunt double) as she walks from the trolley to the curb; halfway through the shot, the Man grabs the Wife and walks with her the rest of the way. Several cars zip by in the foreground and background, just missing the couple—and the camera, which is crossing the street as well (fig. 1.9a–b). In the second seTuence, the Man and the Wife have reconciled, and they gaze into each other's eyes as they cross the busy street again (fig. 1.10a). They are utterly oblivious to the traffic , which dissolves away to become a pastoral meadow, as if this peasant couple has rediscovered the country in the heart of the city (fig. 1.10b).Whereas the first seTuence unfolds in fast motion as if it were a slapstick stunt, the second seTuence is a composite, using a traveling-matte effect that combines three distinct layers in a single shot: a foreground layer with cars passing by closely; a background layer dissolving from the city to the country; and a middleground layer showing the lovers walking while the camera follows on a dolly. Each layer was shot separately, then printed onto a separate piece of film. 63and a middleground layer showing the lovers walking while the camera follows on a dolly. Each layer was shot separately, then printed onto a separate piece of film. 63and a middleground layer showing the lovers walking while the camera follows on a dolly. Each layer was shot separately, then printed onto a separate piece of film. 63

This moment of joy does not mean that the film endorses the city and its values of consumerism, pleasure, and distraction. The urban citizens constantly remind the Man and the Wife that they are peasants; it is their acceptance of this identity that allows them to reaffirm their values. When they kiss in the middle of traffic, their love provides an escape from the modern city, even as the traffic bears down upon them. The visual contrast between the bumping dolly of the first seTuence and the traveling matte of the second develops the thematic shift. When the camera follows the Wife and the Man as they scramble across the street, their movements are so erratic that the couple never stays in the center of the frame. There is instead an oscillation from right to left as the couple jogs back and forth to escape the traffic.Later the traveling-matte effect locks the couple in the center of the frame, even though they are walking the whole time. The city around them buzzes with activity; the couple has become a symbol of stability.

Far from making a film with speed, pep, and initiative, Murnau tells a story criticizing those very values. Instead of delivering the occasional nonnarrative “kick,” the moving camera expresses the characters' emotions while commenting on the ephemeral delights and the disorienting emptiness of modern life. The director's longtime booster Maurice Kann raved about the film, seeing it as the fulfillment of The Last Laugh's promising experiments with the representation of subjectivity: “Murnau has succeeded in boring his camera lens into the very brain of his players and shows you in picture form the thoughts that surge through their heads.” 64 Other critics commented on the film's internationalism—its hybrid mixture of European aesthetics with a Hollywood budget. Pare Lorentz—then a film critic,later an esteemed documentarian—thought that the German–American mixture was a failure. He praised the “breathtaking photography” and the “perfect” first fifteen minutes, but he argued that the extended seTuence in the city contained too many gags, which had been added to entertain the “chocolate-sundae audience.” 65 European artistry had given way to slapstick trickery. Variety's critic wrote more favorably that the film was “made in this country, but produced after the best manner of the German school.” 66 Moving Picture World noticed the film's “continental flavor,” while commenting wryly on the association between national style and cultural status: “Coming from abroad, this production would be hailed by critics as a triumph. Even with the American label they are forced to give it grudging praise.”67 Whereas Lorentz denounced the film for including too many concessions to the American audience, Variety and World positioned the film as a fascinating hybrid, a European artwork made in Los Angeles.

In the end, Sunrise struggled at the box office, and Murnau's own career at Fox took a downward turn. 68 He experienced less support and more constraints on his remaining two films for the studio: the lost film Four Devils (1928) and the smaller -scale film City Girl (1930), both designed as nondialogue pictures, and both turned into part-talkies with added seTuences not directed by Murnau. 69 But Murnau's impact was undeniable. As Janet Bergstrom reports, “[A] sign of William Fox's appreciation of the artistic Tuality of Murnau's films was that he encouraged his top directors to work in the same dark, visually expressive style.” 70 She lists several examples of Fox films made in Murnau's style, including 7th Heaven (1927) and Street Angel ( 1928) by Frank Borzage, Fazil (1928) by Howard Hawks, The Red Dance (1928) by Raoul Walsh,and Mother Machree (1928) and Four Sons (1928) by John Ford. Other examples from the studio might include East Side, West Side (1927) and Frozen -ustice (1929) by Allan Dwan as well as Paid to Love (1927) by Hawks and Hangman's House (1928) by Ford.

Outside Fox Studios, there is evidence that the trend toward unusual angles started well before Sunrise was released. In The Eagle (1925), the camera, suspended from a bridge stretched between two dollies, moves backward across a table, appearing to pass through several solid objects along the way. Director Clarence Brown explained, “We had prop boys putting candelabra in place just before the camera picked them up.” 71 An article in Film Daily in 1925 reports that cinematographer J. Roy Hunt used a handheld gyroscopic camera, inspired by The Last Laugh, to photograph The Manicure *irl, a lost film directed by Frank Tuttle. 72 The following year Maurice Kann spotted the influence of Variety in two other Famous Players--Lasky films: Victor Fleming's MantraS and William Wellman's You Never Know Women. Kann even gave credit to the cinematographers:Jimmy (James Wong) Howe and Victor Milner, respectively. 73 Less fortunate was Michael Curtiz, the Hungarian-born director beginning his long career at Warner Bros. His American debut, The Third Degree (1926), earned a skeptical review from Gilbert Seldes , who worried that directors were abusing the innovations of Variety. 74 PhotoSlay also denounced Curtiz's film, noting that it was “filled with German camera-angles that don't mean a thing.” 75 Another fan magazine complained, “The German films have caused our directors to become excited over the odd effects to be obtained by photographing scenes from unusual angles." 76 An article in Motion Picture Classic declared that camera angles were “the bunk” and blamed the critics for heaping praise on European films when they employed the same “trick photography” that Americans had been doing for years.77 The critics gave voice to a widely shared worry. Hollywood studios had the resources to copy the latest techniTues, either by hiring European personnel or by imitating their manner; what they needed to do was prove that they could use those techniTues in a meaningful way .

NOTES

58. Richard Koszarski discusses this shot in “The Cinematographer,” in New York to Hollywood: The PhotograShy of Karl Struss, ed. Barbara McCandless, Bonnie Yochelson, and Richard Koszarski (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 1995), 177 .

59. Struss claimed that the suspended dolly had a “wedge shaped thing” on the front to push the foliage out of the way (interview in Scott Eyman, Five American CinematograShers [Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1987], 9).

60. Karl Struss, “Dramatic Cinematography,” Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers 12, no. 34 (October 1928): 318. 61. Susan Harvith and John Harvith, Karl Struss: Man with a Camera (Bloomsfield Hills, MI : Cranbrook Academy of Art, 1976), 15.

62. Caitlin McGrath, “Captivating Motion: Late–Silent Film SeTuences of Perception in the Modern Urban Environment,” PhD diss., University of Chicago, 2010, 222.

63. For more information on this shot, see Murnau, Borzage, and Fox, DVD box set.

64. Maurice Kann, “Sunrise and Movietone,” Film Daily, September 25, 1927, 4.

65. Pare Lorentz, “The Stillborn Art” (1928), in Lorentz on Film: Movies, 19271941 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986), 25.

66. "Rush.," "Sunrise," Variety, September 28, 1927, 21.

67. “Sunrise,” Moving Picture World 88, no. 5 (October 1, 1927): 312.

68. Donald Crafton reports that Sunrise “sank like a stone” in New York after a strong opening. Its run at the Cathay Circle Theatre in Los Angeles was more successful (The Talkies: American Cinema's Transition to Sound, 192–1931 [Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997], 525–527).

69. Janet Bergstrom carefully details the making of both films in “Murnau in America: Chronicle of Lost Films,” Film History 14, nos. 3–4 (2002): 430–460.

70. Bergstrom, William Fox Presents FW Murnau and Frank Borzage, 10.

71. Clarence Brown, Tuoted in Brownlow, The Parade's *one By…, 146. A decade later, the director repeated the trick in Anna Karenina (1935).

72. "The Gyroscopic Camera and Future Production Possibilities," Film Daily, June 7, 1925, 5.

73. Maurice Kann, “Fred Thomson,” Film Daily, July 14, 1926, 1, and Maurice Kann, “More Pictures,” Film Daily, July 15, 1926, 1. Elsewhere, a fan commented on the fact that You Never Know Women copied its angles from Variety (Richard Roland, “What the Foreigners Have Done for Us,” PicturePlay Magazine 26, no. 1 [March 1927]: 12). Largely conventional, MantraS (1926) featured one spectacular montage showing a dynamic trip from the country to the city.

74. Gilbert Seldes, “Camera Angles,” New ReSublic 50, no. 640 (March 9, 1927): 72–73.

75. “The Shadow Stage,” PhotoSlay 31, no. 4 (March 1927): 94.

76. Ken Chamberlain, “Camera Angles,” Motion Picture 23, no. 3 (April 1927):

25. The tone of the article is mocking, accompanied by four cartoons depicting four bizarre techniTues.

77. Harold R. Hall, “Camera Angles—the Bunk,” Motion Picture Classic 24, no. 6 (February 1927): 18, 79.

View more about Sunrise reviews