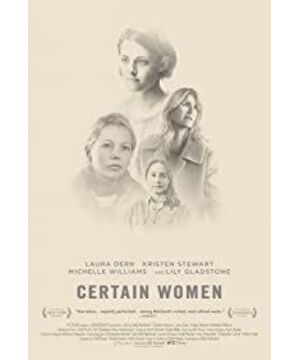

CERTAIN WOMEN is a microcosmic film-making in its most auteurist stature.

Carving out a sublimely low-key triptych out of Maile Meloy's stories onto the screen, Kelly Reichardt's lucidly orchestrated CERTAIN WOMEN whisks her audience to a small-town Montana, and in each part of the triptych, a woman finds herself flummoxed by a common-or -garden quagmire about human interaction (by turns, professionally, domestically and emotionally) which soberly flouts any sensationalism through Reichardt's brilliant execution.

Laura Wells (a pensive and discomfited Dern), a middle-aged lawyer, is frustrated by the persistent visits of her client William Fuller (Harris, strives for an ostensibly expansive persona but strikingly betrays his disquiet bobbing right underneath the surface), who insists on suing his company for the work-place injury inflicted on him, even after Laura repeatedly explicates to him that it is legally nugatory reckoning with his circumstance, still he won't take her advise seriously, not until he implicates her into a late- night hostage foolery, the episode finds an almost antilimactic pay-off.

The heroine in the second segment is Gina (Williams, exquisitely smoldering in her understated flair), who is married to Ryan Lewis (Le Gros), and they have a teenage daughter Guthrie (Rodier), their marital rift starts to aggravate when they visit an elderly friend Albert (Auberjonois) to buy a heap of sandstone lined up haphazardly in front of the latter's house, which they can use to build their own abode.If Laura's plight is occasioned by exterior intrusion and social prejudice (people tend to believe an authoritative male figure than a female one), Gina's story tackles a more internal frustration within a nuclear family, stranded inside a loveless marriage (right out of the box, Reichardt notifies us Ryan is Laura's part-time lover), Gina seems to have an upper hand over a biddable Ryan and in negotiating with Albert for their house's sake,but Reichardt's observant camera brings home to audience that she is also invidiously victimized or undermined by the male parties here, not to mention being given the short shrift from the pubescent Guthrie. A scathing but tonally placid critique about motherhood, wifehood and being a strong woman allocates the second chapter ample elbow room (for both Gina and spectators) to breathe and introspect.

Yet, a crescendo is crystallized in the third story, about a young girl, simply credited as the Rancher (Gladstone), whose Indian descent is only hinted, takes a horse-tending job on her ownsome, seeks any ghost of human contact out of her monotonous solitude, she stumbles on a night class of school law taught by a young lawyer Beth Travis (Stewart), who has to inure a four-hour drive (one way) for this biweekly endeavor. An unilateral attraction germinates in hugger-mugger , so how far does one can go to venture a possible reciprocation? Most of the time, the answer is always there, clear as day, but no one can blame you for trying, the newcomer Gladstone kills it in her transcendent reaction shots in response of a bewildering nonevent, brimful of subtlety and unfeigned undertow of heart-breaking,Meanwhile Stewart brings about a significant mien of jaded weariness and guarded spontaneity as a wrong-footed, short-changed bottom feeder.

Opting for a less elaborately interwoven structure, Reichardt allows each story to flourish on its own terms without much fragmentation, and only tentatively suggests the characters' tie-ins (Laura and Gina is obliquely linked by Ryan, the Rancher and Laura has a fleeting encounter in her office, that is all), and most extraordinarily furnishes these heartfelt female-centered stories with an incisivecontemporary spin meanwhile upholds her aesthetic integrity to the hilt, CERTAIN WOMEN is a microcosmic film-making in its most auteurist stature.

companion piece: Reichardt's MEEK'S CUTOFF (2010, 6.6/10)

View more about Certain Women reviews