Text / Gucheng

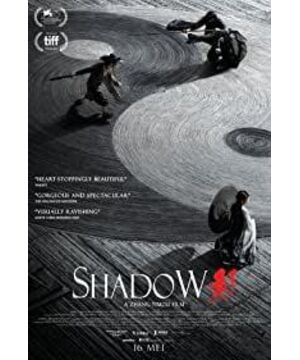

"Shadow" is still the product of the theme first. First, there is a proposition about "shadow", and then the posture is dismantled one by one. Metaphysically there is the opposition between true and false and good and evil, and metaphysically there is a contrast between yin and yang and black and white. In this sense, Zhang Yimou is still lying in his comfort zone, and "Shadow" still shows Zhang Yimou's craftsmanship.

In my opinion, "Shadow" is firstly a landscape, secondly a drama, and finally a movie.

an oriental landscape

Zhang Yimou created an oriental landscape in "Shadow". Peigong lived in the ancient water city in the south of the Yangtze River. The palace was surrounded by water on all sides, closed and inviolable. This is more like another ancient dyeing workshop, with a closed courtyard courtyard, and a yellow dyed cloth ("Chrysanthemum Dou") hanging and fluttering, or another "harem" museum, with a closed courtyard of four-bedroom wives and concubines, and a high-rise The red lantern hanging over the beam of the house ("The Big Red Lantern Hanging High").

These closed palaces, dyeing workshops and courtyards are private and closed. Not only are there many Chinese cultural symbols, elements such as qin, calligraphy, Tai Chi and ink painting are overwhelming, and they are full of ornamental; Strong oriental allegory. Thus, a peeping/cave visual structure is formed, in which there is a mysterious and fascinating eastern landscape, and what is waiting is a western vision, a western gaze.

More precisely, it is the lustful gaze of a Western male audience.

In Zhang Yimou's oriental landscapes, the objects usually placed are the various images of oriental women, from Jiu'er ("Red Sorghum") to Judou, from Songlian ("High Red Lanterns") to Qiuju , they become the absolute protagonists and the only objects in the visual structure of Zhang Yimou's films. Zhang Yimou's films quickly entered the Western field of vision in the early 1990s. The fundamental reason why "Chrysanthemum Dou" and "Raise the Red Lantern" were able to "bloom inside the wall and outside the wall" is that the landscape of these "Oriental women" has changed from a certain To a certain extent, it caters to the eyes of Western males and is the projection of the desires of Western male audiences. They open a "rear window" for the modern West to understand the mysterious China.

This visual structure has been used many times in Zhang Yimou's subsequent works, from "My Father and Mother" to "Ambush from All Sides", from "The Golden Armor in the City" to "The Twelve Hairpins of Jinling".

some abstract female figures

"Shadow" seems to take the audience's attention away from the female body, and casts it on the dominant relationship between the ruler and the subject, the real body and the shadow in the male world. But the object presented in "Shadow" is still an "abstract woman". What drives the plot, the real logic behind the story, is still the triumph of an abstract, capitalized "yin".

This "yin" includes not only the concept of "femininity" in the gender order. Pei Guo's recovery of Jingzhou relies on softness and yin to overcome yang. In the film, a hundred warriors who are neither yin nor yang, twist their bodies on rainy days, break through barriers, and attack cities and villages; Pei (in the hands of women) Homonymous with the word "match") umbrella has become a powerful tool to restrain the Yang (homonym with the word "yang") knives in the hands of men. (Zhang Yimou borrowed the perspective method of ink painting from Chinese classical painting, and also gave the whole film a kind of classical oriental feminine temperament, which is similar to Feng Xiaogang's introduction of a circular frame in "I Am Not Pan Jinlian". The breakthrough in aesthetics will not be repeated here.)

It also includes the metaphor of the "shadow" of the shadow to the real body. In the film, Jingzhou, as Ziyu's stand-in, is a shadow, a dominated chess piece, but has completed a counter-attack from "no real body, no shadow" to "no real body, but also shadows".

It also includes the victory of the "conspiracy" over the conspiracy in the power struggle.

In the film, Zi Yu seems to be loyal to the protagonist, uses a substitute to perform the duties of the governor, and only wants to recover the lost ground. In fact, he lives behind the scenes, strategizing in the dark room, hiding a heart of disobedience, trying to replace him, and finally killing Pei Gong as he wishes. .

Pei Gong seems to be on the sidelines. He didn't reveal Yang Cang'an's identity as an interne, nor did he talk about Po Ziyu's trick of using a stand-in. More often, he just pushed the boat, borrowing other people's chess pieces, practicing his own conspiracy, and finally regaining lost ground.

Jingzhou seems to be the shadow of Ziyu, willing to be a pawn in the hands of others, but in fact he has his own desire signifier from beginning to end - to become the husband of the real wife Xiao Ai, or to replace the real body. In the film, Xiao Ai once asked Jingzhou, "You have many opportunities to refuse to become a stand-in and escape, why don't you escape?" Jingzhou said, "Because these are also your wishes." In the end, Jingzhou not only killed Ziyu, but also died Pei Gong made up for it, forging the illusion that Pei Gong was assassinated by an assassin (Zi Yu wearing a mask), completely freed from anyone's shackles, refused to be anyone's shadow, and became the existence of the oriole behind.

A Shakespeare play

Some people say that Shakespeare's sense of drama is revealed in "Shadow", and the shadows of "Macbeth" and "King Lear" can be seen. In fact, Zhang Yimou's films are more like a drama.

From "Red Sorghum", Zhang Yimou has made a precise cut between literature and drama. He attaches great importance to conflict, distinguishes between love and hate, expresses emotions straightforwardly, simplifies vague areas, ignores details, and seldom uses techniques such as "grass snakes and gray lines" in literary works. Therefore, although most of his early films were adapted from novels (Mo Yan, Liu Heng, Su Tong, and Yu Hua), they had a completely different flavor from the novels. What the audience sees is extremely gorgeous characters, wild emotions gushing out, grand drama, and stories that seem to condense everything about desire and death in the world.

The same is true of "Shadow", Zhang Yimou magnifies the dramatic conflicts of different characters, forming multiple binary oppositions, such as Peigong and Ziyu, Ziyu and Jingzhou, Yang Cang and Jingzhou, Xiaoai and Ziyu, the relationship between them. Separation, suspicion and confrontation have become the main driving force for the development of the storyline, and audiences are often interested in the games and wrestling hidden under the conflict.

These binary oppositions, combined in pairs, form multiple entangled "triangular relationships", such as Peigong, Ziyu and Jingzhou, Peigong, Yang Cang and Ziyu, Ziyu, Jingzhou and Xiaoai. The trade-offs and mutual checks and balances have become the inherent tension in Zhang Yimou's films.

Interestingly, in "Shadow", whether it is between Peigong, Ziyu and Jingzhou, or between Ziyu, Jingzhou and Xiaoai, there is a hidden "love triangle" relationship, implying some kind of Oedipus. Si complex: an aging and powerful man (the impotent id), the former is Peigong, the latter is Ziyu; a young and ambitious man (narcissistic baby), the former is Ziyu, the latter is Ziyu Jingzhou; there is also a woman in a low position of domination (the other who is projected by desire), the former is Jingzhou and the latter is Xiaoai. The narcissistic infant's resistance to the mature id and the alienation of desire projection eventually become the inescapable ending of Zhang Yimou's films.

Just think of Tianqing, Tianbai and Judou in "Judou", or the adaptation of the triangle relationship of "Thunderstorm" in "The Golden Armor in the City", those inseparable love-hate hatred eventually become sinking And lost footnotes, as the film's prologue and epilogue stretch out from the empty theater.

"Hainan Daily"

View more about Shadow reviews