Both Strindberg and the impulse for self-analysis (for the autobiographical component of the film, see an early long report ) can be attributed to the ideological currents of the early twentieth century. There is also the description of Christian issues that Bergman often discusses in the film, about God, about the Jews, it is hard to think that it is a product of the 1980s. The following passage about religious metaphors in movies can also make it difficult for audiences who have become alienated from religion:

What the movie says is that the real magic of the pagan Christian (Alexander) to break the power of the authoritarian Christian (the Bishop), lies with the imprisoned Arabs (Ismael) assisted by the Jews (Isak) and the slightly rebelling Jews (Aron). [1][written by Roy Finch, printed in nytimes ]

The interesting thing is that the priest's image after death is half face Ruined, the other half is intact, and it has to be reminiscent of the former mayor Harvey Dent in Batman. If the image of this Batman series that appeared in the 1940s has anything to do with the image design of the priest scene, it seems ironic. Yet even this picture can be explained in French language:

The Bishop has a monstrous alter-ego, a bearded Aunt Elsa, passive, shapeless, face covered with sores, a constant reminder of his deformed underside, by which he is destroyed. [review by Quart and Quart, published in Film Quarterly]

Also Unrelated is the fact that the arrangement of the priest's house is similar to that of the painter Hammershøi. The latter I came across for the first time in a Danish girl's review. Compared with the aesthetics of the old capital of the grandmother's house, the simplicity of the latter's Baiping method should be more suitable for the taste of contemporary people. Interestingly, this kind of decoration is generally referred to as Nordic minimalist decoration. Even though people generally associate this style with IKEA now, its origins should be earlier, not to mention that minimalism as an art style has become a self-conscious art movement in the 60s.

It does not mean that the works must be explained by the context of the times, but that the works and the times have some kind of connection from the very beginning. In more Marxist terms, the production relations reflected in a work of art are a commentary on the era. Even in Twin Peaks, which was just filmed last year, the audience can feel the wanton paranoia in the film. In the sequel, it is no longer a question of who is the single evil spirit. This seems to be the most interesting part of Fanny and Alexander's work, because the way of thinking and the inconsistencies in the plot are unreminiscent of the eighties.

[1] The Christian metaphor is one of the themes of Bergman's film, and the explanation here is a family's words, and the explanation about Arabia is a bit confusing. There is, however, a certain suspicion of Protestantism in the film (see Royal S Brown's Cineaste review). There seems to be a lot of room for expansion on this point.

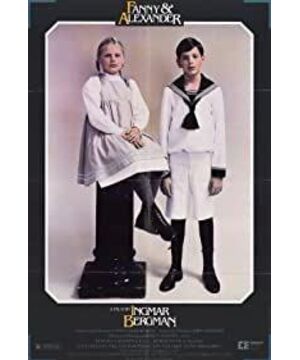

View more about Fanny and Alexander reviews