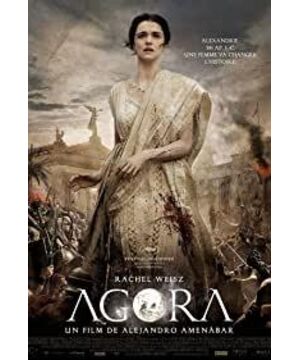

This biographical film about the female philosopher Hypatia is somewhat ambiguous due to shifting perspectives.

At first, it was the perspective of the slave Udas, who silently watched the hostess as a secret lover. [ This perspective was interrupted by Udas's decision to stand in the process of the story, and later he served as a Christian jihad. Some shots Here, we see that when he catches a glimpse of his former hostess on the street, his eyes are evasive. ]; With the intensification of the contradictions between polytheism, Judaism and Christianity and the transition of some violent incidents, the director tends to adopt a cosmic perspective that is detached and overlooking the long river; on some occasions, the heroine finally stands in the narrative At the center of the city, she cares about the city's increasingly disintegrating political ecology, and more often she chooses to immerse herself in solving puzzles about celestial movements; Synnesis), but such occasions are rare.

At the end of the film, Hypatia is captured by the Christians as a witch and ready to be lynched, when the view moves back to Daus, who chooses to kill her before she can be insulted and harmed. This is a sad ending. But what almost brought tears to my eyes didn't seem to be the heroine's "devotion" to scientific truth, but purely from Daus' personal love. The screen inserts some extremely delicate and tender moments when he stayed by the heroine's side in the early years. This flashback of the beautiful moments in life makes people feel extremely sad about the ongoing tragedy. But this grief no doubt dissolves a more general sigh and keeps it entirely confined to the love-hate pain of an ego. [ Even though it appears so strong. ] After wandering about half of the film, the director seems to have finally made up his mind to complete his final position choice in the unification of end to end. [ We will talk about this at the end. 】

In the first lecture given by Hypatia at the opening of the film, she expresses her belief in geocentrism, and eventually she doubts it and tries to find a more plausible answer. In a later conversation with her student Synessis, Synessis accused her of betraying the eloquent teachings she had given to them, and her answer, facing their respective beliefs, "You can't (doubt), and I have to (doubt)." It does sound like the adverbial adverbs and principles of action that a science fighter should uphold.

Another student of hers, a loyal fan and admirer, will be with her in the future, and the protective Admiral Oristis seems to value affection and loyalty [ recall his experience with the polytheists and Christ After the collapse of the first conflict of the believers, the maintenance of Sinaisis, who usually competes with himself. ], when confronted with the question of faith, he would be like a bewildered child, unable to understand why he had made a mistake, and would kneel down and cry bitterly under the more sincere exhortation from Synnesis.

What also puzzled Alistis was Hypatia's obsession with celestial galaxies, which she had explained to him about the "everybody's drunk and I'm awake" joy and glory that could come from unraveling the mysteries of the universe.

"In this second, the whole world is moving, and no one realizes it, only you and me."

In my opinion, the knowledge she seeks [ at least with Hypatia ] is a very practical ability. Implicit in it is power.

From this perspective, it seems understandable to examine the choice of perspective of the overweight Odas. Because from his point of view, it happens that Hypatia's position of power is the best. Her usual care [ applied ointment to him ], praise [ claimed that Udas was more intelligent and wiser than her students in the class ] were more or less out of the kindness and charity of some superior [ so to speak] It seems a little out of place, but when I think about the critical moment when the Christians intend to capture the library, she cursed Udas in a state of anger, and it was this that made Udas feel grieved and indignant, and immediately turned against him ]; When Udas tried to rape her and then knelt down at her feet and cried bitterly, she regained her composure from the initial fear, and "returned" Udas's freedom with a kind of divine tolerance [ instead of like A woman who is hysterical and overwhelmed by the horror of a thug who tries to rape her ].

Hypatia's cowardice and prudence in unraveling the mystery of the heliocentric revolution conic seems more real and "popular" than her recovery after she was almost violated, because compared to her The power of the knowledge mastered, the mystery of the creation of the universe [ or the creator ] is undoubtedly stronger, and for this unknown thing far beyond oneself, even with the courage to challenge, it will reveal some kind of Unbelievable withdrawal [ or, in other words, agitation and fear about the imminent grabbing of the fruit of wisdom ]. After realizing that she might actually have obtained the truth [ through the approval of another elderly servant ], she happily hugged the old servant, and then reposed her posture slightly awkwardly. The gaffe here is closer to a naive woman than when she faced Udas. At this moment, she is more like a taker [ gets some kind of enlightenment, gets some kind of reward, like the humility that has just been praised by the master And the smug former Udas ], not the giver in power.

It is safe to choose the narrative position of Udas, because he is in both the old and the new camps, that is, he does not have the arrogance of elitism, nor does he belong to the blind obedience of the rabble, and can choose to change power with a kind of Unbearable and nostalgic mood erased his once ideals and desires.

View more about Agora reviews