The two shots, front and back, are neat and have the confession of the loser, which is regarded as one of the few effective scenes in this film.

After the movie was over, the aunt in the front seat complained coldly that I kept rubbing the knees on the back of her head, and I did look a little fidgety. Auntie picked up her bag and left, and I took my seat. The film that just ended soon seemed remote, as unfamiliar as the rubble in the Andes.

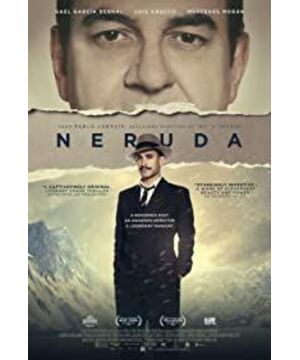

According to reliable sources, Neruda is clearly the legend of Chile, the South American sect of poetry. In addition, he also drink, lust. However, this is probably not much different from many artists or even human beings as a whole. What I want to know more is a complete Neruda, his decisions, his willfulness, how he is so loud and proud, not his drinking Just an image for fun.

The crux of the film is that Neruda's poeticity and his rationality are fractured, and the roles of political task and poet alternate but rarely overlap. This may be what the director understood as Neruda, but if that's the case, he's just a confused communist who writes good poetry.

Neruda fled on the long and narrow territory of Chile, of course, his motive was to avoid capture. The problem is that the source of his determination and the enthusiasm of capture are completely distorted in the film. A small number of insignificant supporting roles must interact with our fat Neruda, but only on the basis of the pre-established understanding that "the poems written by Neruda are liked by all the people in the country, he is really our baby" can we feel the drama. People defend Neruda's zeal, the film doesn't explain Neruda's journey to becoming a poet, he's already a poet, and we seem to have to swallow it. It's like people who don't know Batman's upbringing will naturally wonder how he is so rich. The birth of a hero needs a solid plot to promote, and a few strokes depict the deep love of Neruda's works. Chile has produced such an appealing poet. I can understand this and I can be moved, but this kind of moving is like feeling the event itself, not so much about Neruda on the screen. It’s like listening to Dunke if there are no photos. Erke's Great Retreat can also make people feel the same. In this mood, Luis Gnecco's Neruda was completely intriguing. He was like a carrier of a great soul, his eyes, face, and body were too stagnant.

There are many others that can be criticized. For example, the film is obviously shot with daylight negatives such as Kodak 250D without color correction. It is a complete distraction. If a film needs to use a "violet-like picture" to restore a combative poet, the photography department is obviously a bit overwhelmed. Excessive lighting effects and an obsession with shallow depth of field make the film itself inconvenient to watch, everything is too dazzling, and character interactions are often in an aura of anachronistic brilliance. Only a few close-ups of Neruda were effective, but the editing couldn't hold back, so the audience couldn't see through Neruda's private side, which is similar to the shallow depth of field used in The Handmaid's Tale earlier this year. The approach to narrative elements is fundamentally different. Of course, the weakness of editing is difficult to ignore in many scene changes. In the end, the poetry of snow chase is often trivialized by popular and simple pictures, and the plot is trivial for a long time. It is better to leave Oscar alone in the snow. Struggling and babbling come through.

The director's intention is very obvious. He wants to restore the interaction between the poet and the masses, and use this to shape the story of Neruda and Oscar's murder and love (if the director really thinks that love and murder can only be achieved by the detective and the arrested) If it can only happen in between, it is really acting stupid). But both Neruda and Oscar were too jerky: Neruda didn’t want to act, the editor wouldn’t let him go on, and Oscar felt too young, too fussy, or, in other words, too acting. Oscar, the film's unquestioned second lead, needs a stronger character. At the end of the day, I can't understand how a thin, suave, and lacking in means could be assigned by the president to hunt down the most wanted man. This is a question of character design, and the pursuit of Neruda cannot break through it, and it becomes an image poem that is neither embarrassed nor embarrassing, breathless.

View more about Neruda reviews