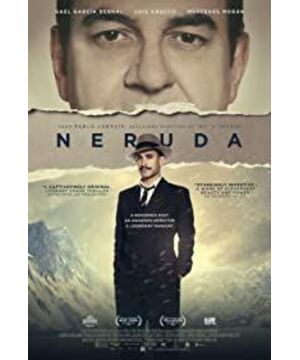

If you don't like "The First Lady," then you can try "The Hunt for Neruda." Although they are from the same director, Pab Lolarain, they also cut into the characters from the political background, and also only intercepted a stage in the protagonist's life. They also have dark tones and unique camera styles. Very big difference. "The First Lady" is still a decent biography, with the exception of Natalie Portman's over-the-top performance, which is overly mediocre. But "The Hunt for Neruda" goes further in the form of a biopic, allowing this deeply rooted historical celebrity to escape from the descriptions of books, biographies, and encyclopedias. The film opens with a swivel of the camera following Neruda into the Senate bathroom. The communist senator and the people's favorite poet lashed out at the Chilean president, who betrayed leftist support and turned to the United States. The Communist Party was purged and oppressed by the establishment, and Neruda, who publicly criticized the President, was impeached and pursued by the President's wing. Mr. President was jealous of his popularity: "This man has only to reach out and take out a piece of paper from his pocket, and ten thousand workers will be silent and listen to him recite the poem in that special voice". Pelucianu, a serious and tight policeman in a suit, appeared at the right time. The young man who believed himself to be the sheriff's son had been chasing Neruda, from brothels to streets, from bustling cities to the desolate Andes, but always allowing the cunning poet to escape at the last minute. All history records Neruda's irreversible ending in this story—he managed to escape to Argentina and into exile in Europe, continuing to sing the praises of the world he loved. The film, on the other hand, gives Pelucianu an ambiguous ending—death or rebirth. A Meaningful Neruda - Ebullient Stalinist, People's Darling Neruda as we know it, a fiery communist, a former politician in exile, a Nobel Prize winner poet. Neruda under Laraine's lens gives this character a richer meaning. He not only loves the people - he has recited poetry for male prostitutes who disguised themselves as women, and put coats on ragged beggars, he is also the darling of the people. ——The communists ensured that he had no worries of food and clothing on the way to escape, the prostitutes and poor people concealed his whereabouts for him, and even the farmer was willing to bless him to escape the pursuit. But he was also the supreme defender of the Soviet regime - Stalin's "lover". He believes that only Soviet democracy can save the people, even if the presidential palace will be covered with broken peanut shells and broken wine bottles, and the laws will be misspelled, but "the cemetery will no longer be full of executed political prisoners. ”, without realizing the truth of Gulag’s nightmare, his innocence and blind enthusiasm as a poet. Neruda was also a reveler who indulged in the spirit of Dionysus, never rejecting women's pursuit and materialistic pleasures. He is Lawrence of Arabia at the ball, stroking the white horse and reciting "The saddest verse I can write tonight". He does not deny the privileges he has in the Communist Party, and he defuses doubts with a joke in an argument with a drunken female party member: After communism is realized, everyone will be like him "eating in the kitchen and fornicating in the bed. "He is a kind person in the mouth of his first wife, and he calls his second wife Delia "little ants" in an intimate tone, but he often can't bear the loneliness of seclusion and the prostitutes drink and revel all night. Laraine does not have much political and value-biased judgments on the poet, neither eulogizing, sympathizing, nor belittling, but loyal to his poetic spirit of extreme romanticism and liberalism. The film's emotion for this character is more out of love for this people's darling. The further away such a Neruda is from the history textbook, the more bold and incisive it is. Pelucianu, who created and was created - poetically close to Neruda, narratively close to Borges But Neruda is not the only protagonist of this film, it creates another: Oscar the hunter Pelucianu. This has also become a breakthrough for the film beyond the biographical format. Before the character's official debut, his first-person inner monologue as a voiceover accompanies Neruda's appearance and runs throughout the film. The monologue from the police shakes the position of Neruda as the protagonist, which is not only a game between fictional and real characters, but also a resonance between virtual and reality. Peluccianu is both a participant in the hunt, an oppressor who hunts down the Communists, and a calm and restrained bystander in voiceover, the antithesis of the fanatical, liberty-seeking poet. There is no limit to his self-narration. It seems to come from a specter who foresees the cause and effect of events, always with the poet who acts one step ahead of him, treating the unknown as irretrievable as the past, observing Neruda's every moment with cold-eyed sneering. An action, every escape, every recitation. The narrative, led by Pelucianu's voiceover, creates a poetic labyrinth that disorients viewers who follow his perspective to explore the story. Through the mouth of Delia, the film declares Neruda's creative sovereignty over the manhunt story, as well as the fictional nature of the police character: "In his script, we all revolve around the protagonist... He created you, wrote you as A sad policeman". Pelucianu, on the other hand, rejected his fictional and supporting character, saying: "In my story I caught him and I put him in jail. I would put him to sleep and watch him dream. ". Who is the author of this story? Did the director and the playwright arrange the fate of the protagonists? Or did Neruda, who was keen on hunting games, devised this grand escape? Or is Pelucianu, a careerist who is determined to make a name for himself in history, rewriting history? Who is the reader of this story? Is it the audience who is watching the fate of the protagonist? Neruda, who loves detective novels? Or the policeman who is portrayed as a presidential lackey but is getting closer and closer to the poet in spirit? The grand hunt and escape culminated in the Andes Mountains in southern Chile. From cars to motorcycles to horses, from a massive raid by 300 policemen to a single-handed chase, Peluccianu's situation turned sharply into the disadvantage of being alone. On the verge of death, Peluccianu shouted Neruda's name in the snow: "Pablo! Pablo!" But his inner monologue was "I've been chasing the eagle, but never Can fly." Neruda followed the gunshots and walked in the direction of his pursuer. Eventually they met, and Neruda described his pursuer this way: "Yes. I know him. He is my police officer, my persecutor." Coincidence: "My ghost in police uniform. I dreamed of him, and he dreamed of me. He observed me, investigated me. You see what officers you wrote, you wrote snow and horses. You shaped I." Peluccianu's monologue is full of Neruda-like poetry and metaphors, and the character is created in a way that is closer to Hugo and Borges in a literary sense. Like Jean Valjean and Javert, Hugo's greatest fugitives and most persistent pursuers, Pelucianu and Neruda made and shaped each other. Javert lived in a hard labor camp since he was a child, and he was immersed in the sheriff's father and his father's constant "words and deeds", so that this character was branded as the guardian system to carry out orders, which was the fate he could not get rid of. Javert's maintenance of the system and hidden compassion made Jean Valjean's light under suffering. Jean Valjean's repeated escapes and tolerance and kindness broke the meaning of Javert as a government tool, and perfected his role as a common man. human meaning. Pelucianu, on the other hand, took Javert's fate one step further and began to write his own destiny. Initially, Peluccianu was branded with the common brand of these villains: the lackeys of the regime and the system, the cruel and unsmiling police. However, in the process of observing and chasing the poet, he began to read detective novels and poetry collections left by the poet on purpose, kissed the poet's first wife, followed the poet's trail to southern Chile, and continued to explore and enrich his own significance. If Neruda's political stance and romantic sentiments have historical records, Pelucianu is like a blank canvas that can be painted at will. His mother was an unnamed prostitute, and his father could be anything from a nobleman to a commoner, a farmer and worker with just a few coins, or a police chief with supreme power. The ambiguous and untraceable origin of Pelucianu's origin is as imbued with fluid meaning and uncertain identity as the fictional nature of the character. His awakening is like the audience in Borges' novels who participated in watching the drama of their own destiny, and those who put themselves into the text of the novel and become the protagonist's narration of their own experiences. At the time of his death, Peluccianu finally broke free from the role he was supposed to abide by in the traditional narrative: the antithesis of the great poet, the grasping tooth of the authority, the ruthless enforcer, and the role that Neruda had assigned him to him. Trap: a sad cop who is limited to self-knowledge, but personally participates in, writes, and directs the tragedy of his own destiny , and realized that he was feeding back the character of Neruda, and became an important role in the story of the poet's escape. Peluccianu's monologue ends with the words: "I came between the lines, and now I'm flesh and blood." This is the ambition behind directors and screenwriters, who, like Borges, find ways to make characters into their works Fictional readers and writers, and this fiction will eventually extend into a bolder attempt to invade reality, drawing fictional characters into reality and audiences into novels/movies. The film's somber gray-blue tones, briskly swirling shots, and shifting dialogue scenes contribute to this psychedelic temperament that mixes fiction with reality.

View more about Neruda reviews