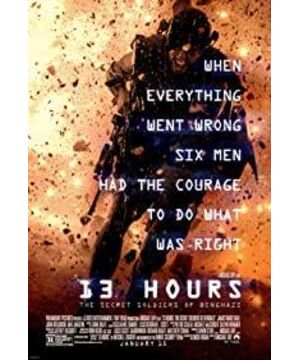

Then the three-act scene of "13 Hours of Crisis" should be like this:

1. Six mercenaries were ordered to protect the CIA intelligence station in Libya. They quickly adapted to the environment and completed several protection tasks excellently.

2. The U.S. ambassador from Libya came to Benghazi to carry out diplomatic activities. He was attacked by the local armed forces. The mercenaries in critical condition set out to rescue, but the mission still failed.

3. The intelligence station was unable to protect itself. The mercenaries exchanged fire with the local armed forces and suffered heavy casualties. However, they finally left Benghazi after the rescue of the United States.

The book says that understanding movies in this way is very helpful for writing excellent movie reviews. Is this really going to be the case? I tried it today. Building a skeleton should be the basic quality of a good screenwriter. The above three points are the veins for the screenwriter of this film to deal with the story. With the skeleton, the rest is to add flesh and blood to the skeleton to make it look more plump. Of course, you can also use this to design characters. For example, adding a female intelligence officer to the intelligence station, how to have a good relationship with her and go out with her to complete the main plot of the first act. Thirteen Hours of Crisis Due to its small time span and relatively simple storyline, the rhythm of progress is relatively obvious. As long as the interval between the fierce battle and the truce is handled well, the story is basically complete. Because it is based on real events, the jumping back and forth between reality and fiction can make people feel like returning to the scene. In short, it should not be difficult for a gunfight film with bullets to fly as long as it captures the texture of the battle.

Although American films of this type are also their main theme films, the values they promote are naturally theirs. However, they tend to be more realistic and sometimes sympathetic to the enemy's side. Although the enemy can be shot, they can also be sympathized with. They also have family members and parents, and they do not live in a vacuum. The battle scenes are more realistic, perhaps because Americans are all gun masters, and their directors at least know that light weapons can never beat heavy weapons, and that bare hands can never beat guns. It is absolutely impossible for people in foreign countries to escape without the help of foreign allies. Film or TV can be artistic, but making it real is to respect the audience's IQ. For example, in the thirteen hours of the crisis, the ratio of battle losses between mercenaries and local armed forces is extremely disparate, but this result is due to the huge gap in weapons and equipment and the training quality of personnel. This feels quite convincing. And even the Americans who occupy the commanding heights are at a loss when they encounter the enemy using mortar attacks. Fighting has always been because you set up an encirclement and occupying the commanding heights can obliterate the huge gap in weaponry and personnel quality. But the directors of our domestic war films often don't understand this. It's ridiculous!

View more about 13 Hours reviews