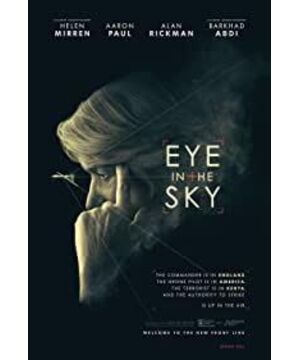

"Eye in the Sky" is a concise, discreet, insightful and powerful film. From a large number of images from God’s perspective, parallel perspective and monitor’s perspective, to the three games of anti-terrorism legal mechanism, political risk, and moral examination discussed, they are all presented in a clear, transparent, and smooth transition of time and space. The most important thing is the first release, which makes this seemingly small-scale war-themed film set off changeable waves in a highly time-condensed game story. The film tells the story of British Colonel Catherine, played by Helen Mirren, when he captures a female terrorist who has been tracking for six years, but the US drone investigators of the joint operation unexpectedly discover that the terrorist is plotting a suicide bomb attack. To prevent damage, Catherine orders the bombing of the secret base to wipe out the enemy. When drone pilot Steve (Aaron Paul) takes aim, only to find a girl in his attack range, is he still bombing and hurting the girl? Still delaying the bombing to save the girl, but at the risk of a suicide bomb that could hurt 80 people? What was originally a simple cross-border arrest operation instantly turned into a complex and inexplicable counter-terrorism mission. The generals, ministers, justice ministers, female political advisers, and foreign ministers in Singapore who were sitting in the command room of the British cabinet staged a political risk kick. The game, while the generals played by Alan Rickman and Colonel Catherine insisted on tough anti-terrorism execution, which strongly contributed to the legal continued bombing missions of military laws, which formed a strong conflict with the tedious and slow approval decision-making system of the British cabinet. And everyone involved in the action is also under moral scrutiny. As the girl turns the sound of the hula hoop at the beginning of the film, the sound of the propeller of the drone is synthesized, and the camera gradually moves up to form the perspective of God, establishing a three-layer surveillance relationship: real-time information of drones, surveillance birds, and surveillance bugs Feedback to the cabinet command room and various war rooms forms a kind of surveillance for everything that is happening in the field of terrorist activities, and the cinema audience also forms a surveillance view of everything on the screen from different viewpoints. Drones, surveillance birds, and surveillance insects create a sense of game and documentary. Except for the perspective of God, most of the film is an objectively presented parallel perspective, which makes the image itself form a sense of balance, objective, and indifferent. everything. The impetus of these games is all tied to the little girl. The moral dilemma of "injuring the little girl together or taking the risk of possibly harming 80 people?" is easily reminiscent of the famous "trolley problem". Dilemmas are easily resolved in a utilitarian view. In this case, it was more because after the missed opportunity for bombing without collateral damage, legal risks and moral scrutiny turned the game in the cabinet's command room into a game of political risk kicking the ball. The steadfast generals insisted on continuing the bombing with the stance of maximizing their interests, while the female judicial advisers objected to humanitarian considerations, and then the ministers, justice ministers, and foreign ministers started a game of shirking responsibility, buried deep in their hearts. Humanitarian considerations, but a political risk unwilling to take. On the other hand, the film also presents the different decision-making mechanisms of the United Kingdom and the United States for counter-terrorism operations. The nervousness of "the video on YouTube could spark a revolution" and what happened in the cabinet command room satirized the lengthy and inefficient decision-making mechanism of the British cabinet to the extreme. The resolute attitude of the US Secretary of State and the special commissioner strictly enforced in accordance with military laws also satirizes the decision-making mechanism of the British cabinet. The general and the colonel in the film are also flesh and blood people. After the operation, the general took the toy he bought for his granddaughter and went home. The sad expression in the colonel's car window is a kind of echo, but because of their anti-terrorist military status, they understand the meaning of war better. What, the general's statement to the female political adviser after the operation, "Don't tell a soldier he doesn't know the cost of war," points out the point of consideration. Everyone in the film is subject to their own moral scrutiny, but the closer the battlefield is, the more serious and urgent the British Foreign Secretary is in the command room, who can answer the phone on the toilet. And the pilot who drives the drone and presses the two missile buttons and the female technician who assists, the "collateral injury" data analyst will be branded with heavy moral torment. And such moral scrutiny is not one-way. The militants who unloaded their weapons to help the girl send the girl to the hospital, and the local agents who were dejected for not rescuing the girl are all adding to the multi-faceted moral weight of the film. In addition, there are three impressive staring close-ups in the film, Colonel Katherine staring at the terrorist on the wall in her home office, the stare of the drone driver Steve looking behind the car when he first appeared, the girl's father looking up at the sky, They are all unconsciously involved in this abyss, but they cannot change. When all this is over and the news comes out, just like Aeschylus's title in the title line "In war, truth is the first casualty." Maybe what we see is not the truth, but enough is left. of grief and re-examination of war.

View more about Eye in the Sky reviews