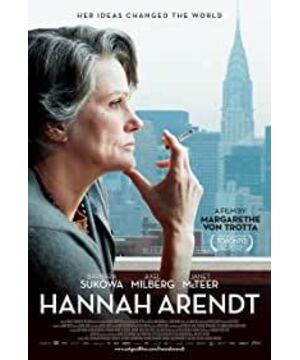

Years after those sizzling years, Eichmann in Jerusalem was either condemned or defended, and rarely viewed as a book worth reading and understanding. So when I heard that German director Margarethe von Trotta was going to make a film about Arendt covering Eichmann's interrogation, I had some concerns. But in a half-century of critiques of Arendt's hyperbole, the film Hannah Arendt reaches unheard of depths, and a height rarely seen in any biopic: it actually makes us reinvent the wheel. Focusing on Arendt's work provides us with a convincing, accessible focal point.

The movie begins with two wordless scenes. The first scene depicts the Mossad [12] kidnapping Eichmann. The second scene depicts Hannah Arendt smoking a cigarette and then smoking a cigarette. There was darkness around her. For two full minutes, we watched her smoking. Barbara Sukowa (she won the German Oscar-Lola Award) with passion and tension, Arendt walked slowly. She lay down. She inhales. More strikingly, however, the ashes of that cigarette glowed brightly in the dark. Let's understand: Hannah Arendt is thinking.

Although Arendt's works take a different approach, one theme is clear: in the contemporary bureaucratic society, human evil does not stem from goodness but the absence of thought. Eichmann's claims that he "never acted from vile motives" and "never thought of killing anyone . not totally impossible) to believe". Arendt insists, however, that "Eichmann is not Iago, nor Macbeth," a man who does evil out of evil. Eichmann boasted of civic action, conscientiousness of law-abiding and due diligence; his excellent performance was also affirmed by his superiors. In the dock, Eichmann used clichés and official accents, and he even implied that he was a Zionist and that he "saved hundreds of thousands of Jews". The magnitude of his crimes and the mediocrity of his own made Arendt deeply shocked.

She thought: Perhaps the most heinous crimes in history were committed not by breathless lunatics but by mindless buffoons; she was shocked. This is what Arendt's famous and widely misunderstood dictum "the banality of evil" refers to. It's one thing to kill one's own aunt out of malice; some crimes are indeed out of savage motives. But the distance between malicious murder and administrative genocide is 108,000 miles. Arendt's "mediocre" says that without thoughtless people like Eichmann, things that lose basic judgment on evil and resign to dictatorship would not happen.

The Eichmann interrogation inspired psychologist Stanley Milgram[14] that famous experiment: residents of New Haven were asked to assist researchers in educating students by giving students who answered wrong questions (they thought they were ) painful (and potentially fatal) electric shock. Most assistants follow instructions. Milgram concluded that most people obey authority, even when its instructions go against their own deepest beliefs. His view is that people do not need to support (an authority) to obey (the authority).

But Arendt doesn't see it that way. Obedience, she insists, involves a sense of responsibility. Arendt was shocked that her critics assumed that thoughtful people would do what Eichmann did. She worries that experiments such as Milgram's would normalize people's moral weakness. In fact, she sees the angry reaction to her book (her critics insist on viewing Eichmann as a demon) as proof that people fear their lack of moral independence and help them resist The ability to think authoritatively.

Shocked by the dangers of not thinking, Arendt spent his life thinking about the activities of the mind. Can ideas, she asks, save many, if not most, of us from engaging in bureaucratic policing evils, such as the administrative extermination of six million Jews? In Arendt's imagination, thought prevents us from simplifying things, from repeating platitudes, and from doing things in a rut. Arendt believes that only thought has the power to remind us of our human dignity, to give us freedom and to help us resist slavery. In her view, such thinking cannot be taught, but only by demonstration. We cannot learn to think through question-and-answer pedagogy or research. We learn to think only through experience, when we are inspired by those whose thoughts fascinate us, when we meet someone who is unique.

In "Hannah Arendt", von Trotta succeeded in expressing that kind of maverick. In the press room, Arendt watched witness after witness testify about the horrific Holocaust. Von Trotta uses some powerful footage from True Trial. We can see: Arendt is touched, her eyes are wide open, her chin rests in her hands, motionless in tearless sympathy. Arendt left the courtroom after an eyewitness (to the chagrin of Mr. Dinor being called off while discussing his theory of astrology and the cross) fainted, weaving his way through some of the Israelites who were dumbfounded and engrossed in the broadcast. These Israelis get carried away with those emotional stories. Arendt would point out: Those stories have nothing to do with the justice of the man. What others call aloof and aloof, here is a testament to Arendt's moral courage, unconventional, philosophical focus.

The importance of Arendt's Eichmann in Jerusalem will not be compromised simply by the correctness of her conclusions about Adolf Eichmann. Arendt's book was so influential because of the original power of her thinking. This book is a work of judgment about a judgment; in the course of that judgment, we come to understand a man's evil deeds. Focusing on that process (trial in German) is a bold strategy in Hannah Arendt, co-written by von Trotta and Pam Katz, to deal directly with the screen Impossible task of expressing thought.

In a flashback about her teacher and former lover Martin Heidegger,15 Heidegger told Arendt that "ideas are a solitary business". Aside from a few close friends, Arendt is always alone in the film; she is accompanied by nothing but her thoughts and the ever-present cigarette. There is a danger here: Arendt's cigarette could become an empty cipher, an obvious symbol. Instead, the cigarette lingered there, moving with Arendt's breath; Arendt listened without saying a word. What strikes audiences throughout the film is the tension in her silence; this tension drives us to think with Arendt: what she observes and what it means. The audience then changes perspective: from observing Arendt to thinking with Arendt. By the time Arendt spoke at the end, she had already figured it out. The film culminates in Arendt's speech to a group of college students at a small liberal arts college. The seven-minute monologue, after the film's lengthy collection of evidence, is like a concluding statement in a courtroom, very gripping. Arendt finally said, "The lack of thinking ability has created the possibility for all living beings to commit unprecedented large-scale evils. The external manifestation of this kind of thinking is not knowledge, but the ability to distinguish between right and wrong, beauty and ugliness. I hope: Thinking empowers people and helps them survive a few critical moments, preventing catastrophic consequences.” This entire talk is probably the best verbal expression of the importance of thinking in a movie.

Arendt strongly promotes ideas that require self-respect, a need to feel the difference between oneself and others, even a certain kind of arrogance—the kind that von Trotta displayed on screen. The film faithfully captures this feature of Arendt and his ideas without escaping Arendt's creed: the grasp of one's own uniqueness is necessary for character (formation). Like Emerson, Arendt's writing celebrates the independence of personality. In her view, our democratic desire to pursue equality (like others, not to criticize others) makes the problem of mindlessness worse.

Of course, given the complexity of the material facts, there are some fictions and omissions in the film. What is written by Gershon Scholem [16] is spoken in the film by Kurt Blumenfeld [17]. Even more problematic: Not a single Jew defends Arendt in the film. This creates the illusion for the audience that all Jewish intellectuals do not understand her insights. Most startling, perhaps, is von Trotta's reimagining of Arendt's friend Siegfried Moses visiting her in Switzerland. Siegfried Moses was an Israeli government official whom Arendt met while working for the Zionist organization in Germany. The purpose of his trip was to ask her not to release Eichmann in Jerusalem in Israel. The request appears in the film as a threatening ambush rather than an actual meeting between friends, suggesting that the Israeli government has far more organized hostility toward her than it actually is.

The film as a whole succeeds in dramatizing thinking activities, so these dramatic adaptations by von Trotta are forgivable minor lapses. Making a film about a thinker is a challenge; making a film about a thinker that is accessible and gripping is a huge success. Hannah Arendt herself might be surprised to learn that after more than five decades of controversy over the waning of her ideas, a film promises to spark serious public debate; The original intention of the book. The original title of von Trotta's Hannah Arendt was "Controversy", and a more appropriate (and less commercial) title would have been: "The Most Profound Entry of Arendt's Philosophy into Mainstream Society to Date" Interpretation". The film is indeed an amazing idea.

{Author: Roger Berkovich [18]; Originally published on the website of the "Paris Review" magazine}

[Annotation]

1. The Gestapo was a secret police in Nazi Germany, controlled by the SS.

2. Irving Howe (1920-1993) was an American literary and social critic and an important figure in the democratic socialist movement in the United States.

3. The Jewish Daily Forward, a national newspaper published by Jewish Americans in New York City, had a large readership and considerable political influence during the first three decades of the twentieth century.

4. Robert Lowell (full name Robert Traill Spence "Cal" Lowell IV, 1917-1977) was an American poet.

5. Bruno Bettelheim (1903-1990) was an Austrian-born American child psychologist and author, known internationally for his work on Freud, psychoanalysis, and children with mood disorders.

6. Dissent quarterly, an American left-wing magazine, founded in 1954 by a group of progressive intellectuals in New York, politically opposed to both Soviet totalitarianism and American McCarthyism.

7. Alfred Kazin (1915-1998) was an American Jewish writer and literary critic.

8. Raul Hilberg (1926-2007) was an Austrian-born American political scientist and historian, considered the world's foremost scholar of the Holocaust.

9. The Holocaust refers to the systematic genocide led by Nazi Germany during World War II, in which a total of 6 million Jews were massacred.

10. Lionel Abel (1910-2001) was a famous American playwright, essayist and theatre critic.

11. The Partisan Review was an American political and literary quarterly, published from 1934 to 2003.

12. Mossad is an Israeli intelligence agency.

13. Iago is a character in Shakespeare's play Othello. He is the subordinate of General Othello, conspiring to destroy Othello.

14. Stanley Milgram (1933-1984), American social psychologist. The famous Milgram experiment was conducted while he was at Yale University, also known as the Obedience to Authority Study. The experiments began in July 1961, a year after Eichmann was sentenced to death. Milgram designed the experiment to answer: "Could it be possible that Eichmann and the millions of other Nazi followers who participated in the Holocaust simply obeyed the orders of their superiors? We can call them The murderer of the Holocaust?"

15. Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), a famous German philosopher.

16. Gershom Scholem (1897-1982) was a German-born Israeli philosopher and historian.

17. Kurt Blumenfeld (1884 – 1963) was a German-born Zionist. He was Secretary General of the World Zionist Organization from 1911 to 1914.

18. Roger Berkowitz, academic director of the Hannah Arendt Center for the Study of Politics and Humanity at Bard College, a private university in New York Thought: Hannah Arendt on Ethics and Politics.

View more about Hannah Arendt reviews