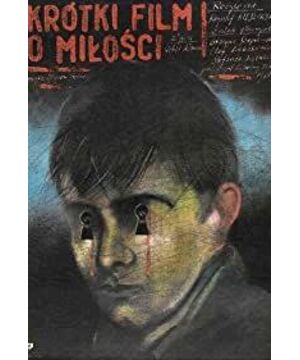

Tomek: "I love you."

Magda: "There's no such thing as love."

Magda asked: "Do you want to kiss me?"

"No."

"Do you want to have sex with me?"

"No. "

"Then what do you want."

"I don't want anything."

This is a classic conversation that takes place on Tomek's first date with Magda.

Love without utilitarian purpose, love out of pure love, love that doesn't ask for anything in return, this is Tomek's love. He applied this principle not only to his relationship with Magda, but also to other things he did, such as telling Magda that he liked learning languages. Magda asks on the same utilitarian principle as love: "What is it for?" Tomek replies: "Not for what. I like words."

Doing things not for utilitarian purposes is Tomek. Not believing that there is no utility in doing anything, this is Magda.

But this film presents us not an angel and a laity. The main characters in the film are not two, but three, in order of age Tomek, Magda, the friend's mother. I can't help but imagine that, at Tomek's age, did Magda ever dedicate love to a person without possessiveness and selfishness? Has Magda's love been teased, insulted, rejected or even played with? In other words, today's Tomek may well be Magda's past, and Magda's present may be Tomek's future. The friend's mother should be the one who has experienced the most among the three. Is her lonely and lonely old age a portrayal of Magda and Tomek in their later years?

Will each of us go through the stages of Tomek, Magda and a friend's mother on the journey of love?

It is said that first love is the most unforgettable. The first love in life is often not mixed with utilitarianism. I liked a person at that time, not because of his ticket, house and car location, but just because I liked this person. The first love is often the most unreserved. But first love is often very painful, and most of them can't be successful, sometimes because they are too young, and more often because the purity of first love cannot withstand the salty anger of reality. This world is destined to be secular, utilitarian, soaked in the smell of banknotes and oil smoke. Even if you are indifferent to fame and fortune and have no desires or desires, it is hard to guarantee that people will come up and spit and step on them. After a few more losses, we learn to do everything for something, to love someone for something, and then we become Magda. Youth has roared away like that train. Sometimes we miss the past too, but we don't have the will or the power to go back to who we were.

But we have no reason to blame Magda. Kieslowski wouldn't even blame her. Because this is life.

What kind of love is Tomek's love? It is said that love is based on understanding, but he doesn't actually know Magda. But his love for Magda can't be easily dismissed as eroticism under the auspices of puberty hormones. His confession to Magda, that voyeurism stemmed from lust, but then that lust was replaced by pure spiritual adoration. Combined with his orphan background, I guess that there is probably an element of admiration, worship, and sympathy in his love. Magda's loneliness, pain, and distinction resonated with him, and he wanted to be nice to her, save her loneliness, comfort her, and make her happy. But no matter what, this is a kind of mutual sympathy on the spiritual level of human beings, which has nothing to do with worldly lust.

Voyeurism is a very interesting subject. From "Rear Window" to "American Beauty", voyeur stories often make people unable to put them down, always wanting to ask "what's the next?" Of course, the directors also enjoy it, putting us and the voyeur's eyes together, let us With the voyeur's lens to peer behind the curtain, and this perspective makes us feel a great sense of power and security. We can see him (her), but the other party can't see us. This kind of perspective is tantamount to God's perspective, but a peeping person is far from the power and power of God.

Tomek wanted to get Magda's attention, but he didn't dare to face her, so he took a voyeuristic approach. Note that he went to the bathroom several times to borrow water, but he was actually making coffee and staying up late to watch over Magda. He lives almost on the same rhythm as her, she goes home, he starts "working", she paints, he watches her, she sleeps with different people, he breaks her heart, she breaks up, he too Painful, she rested, and he also turned off the light and went to bed. This paragraph is very similar to Alexandra's attitude towards Fanfan in Fanfan. He loves her, but he is not sure that he can handle the latter, so he installed a wall of glass next to the apartment that Fanfan rented. He wakes up, does gymnastics, eats, and sleeps with her, but they do not touch. But love can't be maintained by voyeurism without contact, so we see, then Tomek comes out and admits his actions, and Alexandra smashes that glass wall.

What's interesting about the movie is that Magda ends up being a voyeur herself. When she regretted hurting Tomek, but couldn't get in touch with him, she also picked up the binoculars and repeated what Tomek had done. The peeping didn't end until Tomek got home from the hospital. Magda sat down at Tomek's desk, and the telescopic lens gave her a whole new perspective on her life. She has changed from being the object of observation to the subject of observing herself, in other words, she is introspecting. When she jumped out and looked at herself, she saw her longing for love. She hurt Tomek and couldn't touch him yet, but the hurt brought new life. If the scarred Magda can still understand the true meaning of love, will Tomek's heart be healed one day?

Kieslowski is particularly interested in the kind of unit towers that stand icy on the edge of cluttered construction sites. In his Amator and the Ten Commandments, it is the same gray and cold building. The regularly repeated structure of the towers and the cookie-cutter square windows give people a sense of coldness, isolation, absurdity and oppression, like a metaphor for social relationships. And in this seemingly identical window, a scene of human tragicomedy is being staged. Crash said that people in LA live in a strange kind of isolation, where everyone is careful not to touch others. But once in contact, it is a crash.

A similar point Bergman articulates in Cries and Whispers. Touch is a signal of trust, communication, understanding, and a signal to liberate people from the cold prison of self. Touch can do what language can't. Sometimes a hug is worth a thousand words.

The same goes for Tomek and Magda. If you don't touch it, it's already. Once you touch it, it's a collision. Instead, it is voyeurism, which gives everyone a safe distance and guarantees the satisfaction of curiosity about other people's lives. This is probably the greatest irony that modern life has given us.

View more about A Short Film About Love reviews