Does a work of art need to contain that much knowledge? This does not seem to be controversial in painting and music. After all, strict knowledge can only be expressed in language. But novels are different. Whatever scientists and philosophers say, novels can be written in. Therefore, some novels are very heavy to read, and the author seems to want to stew all the knowledge in the world into a pot, and then organize it into a thousand threads and rich metaphors. There are also some novels that are more pure to read, such as Hemingway's novels, which tell stories honestly, polish their skills, and read them without any ideological baggage.

The question is, are novels really suitable for expressing knowledge? If you really want to learn knowledge, you can read textbooks or engage in academics. Other professional papers can't argue for a reason. The novel is put forward in a few words, interspersed in the story dialogue, and it is euphemistically called "discussing XX topics". Even if the author intends to explain the knowledge in a straightforward manner, non-professional readers often read it in a fog, and professional readers can't learn anything. I left a group of arty people, thinking that this book talks about everything, but in fact they don't understand everything.

So as Sontag rightly points out, the content of a work of art is also part of the form. To put it more clearly: When the same sentence or a proposition is put into science, we have to consider what it refers to, how it is defined, what logical results or causality it has, etc.; Consider whether the sentence is beautifully written, whether the thing it refers to is beautiful, whether it is profound, and so on. For example, someone in the novel quotes a sentence from Aristotle, which of course expresses something, but more importantly, this sentence tells us that the person who said it is a thinking person, he likes experience Knowledge, he is the enemy of those anti-intellectuals, etc. Novelists cite philosophers not for their ideas, but to use their ideas as bricks to build their own works.

It is true that intellectuals sometimes just like those knowledgeable works, and they can indeed get a lot of pleasure from a lot of knowledge in novels. But what's there to brag about? It is actually the lower and less pure part of artistic pleasure. It's as if a woman is interested in a certain artist's work because she likes the clothes of the people in the painting. A lover of ancient Greek culture may wish to have a novel depicting the fantasies of Socrates and Alcibiades - but if this novel is well written, it is not because of the culture of Arcibiades . The extra fun this ancient Greek culture lover gets is of the less important kind, not as much as game anime fans love fan stories.

Some novels do not just talk about knowledge literally, but try to talk about a topic at the level of the whole structure of the work. My point is that it is possible to talk about, or "show" something, but don't assume that art can talk about what it is. The author arranges for society to kill the protagonist, and can express a feeling of pessimism or anger, but all this can not replace a statistical survey report. In fact, if not for other factors in the work, these sentiments are no more powerful than a few slogans.

And the more subtle "other factors" in the works of art are actually difficult to explain in the language of expressing the content - otherwise the generalization in the commentary can replace the work. According to my observation, the more mature the knowledge is, the less you need to read the original text, and you can fully learn it from the textbook. The so-called reading the original text is actually learning some unspeakable ways of thinking. Many of the humanities require constant reading of the originals, which is precisely why they are not real knowledge—episteme, something that everyone can agree on. According to this understanding, the humanities are impure knowledge; philosophical novels are impure art - don't take them so high, it's actually about the same as chatting on the street, only much more refined. Of course, don't think so low of chatting on the street. (This is just for people who think that "the humanities are characterized by no single answer.")

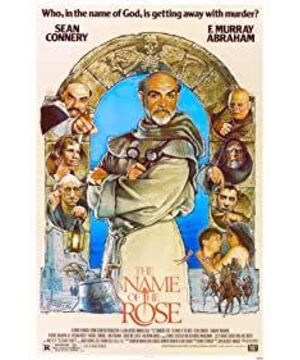

Finally, let's talk about "The Name of the Rose", which is obviously a hodgepodge of art, and the more mixed it is, the more bullshit it is. William is a Socratic character, rational at heart, and thinking about saving a few books before burning his eyebrows. His opponent, the librarian, is a true mind-worm, learning not for knowledge but for authority. I doubt that books would have such magical powers if it wasn't for the excessive worship of language.

However, these questions cannot be fully explored in a single film review.

View more about The Name of the Rose reviews