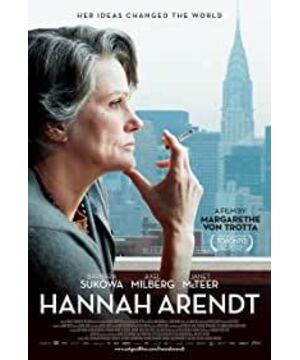

"Hannah Arendt" is still worth watching. The film completes the account of Hannah Arendt's coverage of the Eichmann trial in the everyday life of a high-ranking intellectual. We see female professors complaining about their husbands, the urgency of professors to keep their teaching positions, Arendt's flirting with her husband, and how New Yorker urged the manuscript.

At the heart of the film, of course, is Arendt's reporting of the events of the Eichmann trial. According to my personal observation, there are two main points of controversy surrounding this incident: 1. Arendt condemned the cooperative attitude of the Jewish Council, which made many Jews dissatisfied; 2. Arendt tried to understand Eichmann's behavior and proposed banal evil, which was understood to be a Nazi justification. I largely agree with both.

First, the Jewish Council. It's also hard for me to imagine that the Third Reich could kill four or five million people so efficiently: why didn't they resist? The resistance of four or five million people, even if they were unarmed, was enough to smash the SS. In Arendt's view, the Jewish Council helped Hitler's slaughter: the victim helped the aggressor to slaughter himself. This situation may be explained by the theory of collective action in economics: if other people are different, resistance is almost certain death, but if not resistance, there is still a chance; if everyone thinks so , the end result is that no one will rebel (self-fulfilling prophecy). Anyone who has played Total War: Rome knows that the biggest difference between low-level troops and high-level troops is not weapons, but morale. Units with high morale, such as the Legion of Veterans, can fight to the last man without the eagle falling, while newly recruited civilians will retreat with only a 20% or even 10% reduction in strength. The difference here is a matter of organization and belief. It is a pity that the Jewish Committee was supposed to play the role of a "battle fortress" like a party branch in a company, but it only facilitated the Nazis to organize massacres.

The second point seems to be more popular. I still vaguely remember that when I was still reading newspapers and magazines, the literati occasionally mentioned "the evil of mediocrity", as if to teach mediocrity to the public. The reason Eichmann used to defend himself was that he was just carrying out orders from his superiors and was just a tool. Arendt thinks this makes sense, she believes, because they are willing to be tools and give up their right to think for themselves. However, Arendt does not seem to be able to go further and analyze why they gave up independent thinking. You know, in a bureaucratic system, independent thinking is worthless. Whether in business or bureaucracy, obedience is the only principle. The authority of priests and patriarchs is transformed into the authority of capital, and the boss/boss in the bureaucracy is the embodiment of this authority. Eichmann's logic is actually not as irrational as it appears. Employees of polluting companies will use similar logic to comfort their conscience: this (pollution) is what the company asked me to do, not my own thoughts; besides, if I don’t do it, someone else will do it, and the result is still the same. The requirement of capitalism for laborers is to "take people's money and help them eliminate disasters". As for what to do after taking money, laborers have no right or power to ask. Dry batteries are not responsible for the behavior of the CPU. What Arendt does not understand is that it is capitalism that robs people of the ability (power) to think.

A more thorough view of crime is that all criminals are inevitable products of society. That certainly doesn't mean we shouldn't punish these criminals (as some think Arendt is defending Eichmann). As Marx said:

It can be recognized that the only right that society has in its present transitional state is the natural right to kill the criminals of its own making in self-defense, not the right to try and punish these criminals. ... rather this is a sad but inevitable fact of nature, the sign and result of the impotence and stupidity of modern society; the less society has to use this right, the closer it is to its own true liberation... ...it should be remembered that kings, oppressors and exploiters of all kinds are just as guilty as criminals who appear among the masses. They are all villains, but not sinners, because, like ordinary criminals, they are all products of the willless organization of modern society. It is not surprising that the revolting people would kill many of them in the early days; it would be a misfortune, perhaps inevitable, but as insignificant as the devastation caused by the storm.

I also haven't read Arendt's New Yorker article, so I'm not sure about the wording of her article. We can guess, though, how people would react if she put this passage in the article (which she certainly doesn't).

View more about Hannah Arendt reviews