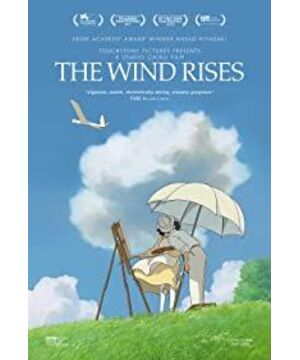

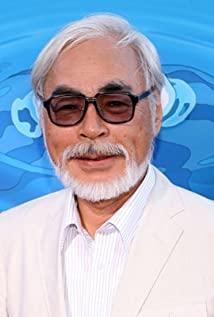

Who is Hori Chenxiong? He is a Japanese novelist in the first half of the 20th century, a contemporary of Jiro Horekoshi, the protagonist of the film (Horitsu was born in 1904, Hori Tatsuo was born in 1903), and he is also a close friend with another well-known writer, Akutagawa Ryunosuke. Hayao Miyazaki's film "The Rise of the Wind", to be precise, is an adaptation of the story of Jiro Horekoshi's first half of his life, adding plots from Hori Tatsuo's novel "The Rise of the Wind" (and other works).

This work has two main lines: Erlang's airplane dream, and his love story with Nahoko. As far as I feel, to understand this film may be viewed in two contexts:

first, this film is Miyazaki's tribute and reflection on Jiro Horekoshi, Tatsuo Hori and the era they lived in. Compared with Miyazaki's previous works, "The Wind Rises" presents a very strong sense of the times. It has a concise but accurate description of the restlessness of Japanese society in the 1920s and 1930s: the relatively open era of the Taisho period has ended, and the economic boom In the downturn, the gap between the rich and the poor is serious, the social atmosphere is depressed, the military is increasingly belligerent, and Japan is heading for war. For Hayao Miyazaki, a group of Japanese who grew up from the end of the war to the beginning of the postwar period, "war" has always been an important subject for thought, including the recent constitutional disputes in Japan (Miyazaki himself has made many related speeches), It can be said to be the remnants of war. The issue that the film "The Wind Rises" intends to explore is: What is the relationship between individuals living in that era and the real environment? Can the meaning of personal life transcend the times?

Furthermore, I personally think that this film is actually semi-autobiographical in nature. Fans who are familiar with Hayao Miyazaki's works must have thought of his other movie "Porcupine" with the theme of airplanes (with middle-aged uncle) when watching this film: from the theme of the story, the bridges and even the aircraft craftsmanship in the 1920s The characterization of these two stories can see the connection. As we all know, "Porcupine" released in 1991 is a retrospective of the career of Hayao Miyazaki, who was nearly fifty at the time. The discussion of Jiro Horetsu's life and dreams in "The Wind Rises", in my opinion, also implies Miyazaki's review and reflection on his creative career. These two films are a must watch together.

So I strongly recommend: If you want to watch "The Wind Rises", be sure to go and watch "Porcelain" first. Understanding Red Pig definitely helps to understand The Wind Rises, and Red Pig is super fun. Good pig, don't you see? (Pushing the pit) -- Jiro Horekoshi, the protagonist

of "Responsibility for War" , has been fond of airplanes since he was a child, and dreams of becoming an airplane designer.

In his dreams, he met the famous Italian designer Giovanni Battista Caproni. Throughout the play, he and Caproni met in dreams many times, and each dream echoed the turning point of the plot.

When we first met, Jiro was a ten-year-old(?) child. In the dream, Caproni took Erlang to visit the plane he built, which ignited Erlang's dream of building an airplane... Sounds like a very bright story, right? But here Miyazaki still said through Caproni's mouth, "They (pilots) are going to fight the enemy. Less than half of them will be able to come back..." And at the beginning of Jiro In the dream, he flew a plane soaring in the sky, but was hit by a bomb and fell. That is to say, the shadow of war always exists, and Erlang has realized since he was a child that the plane is to become a weapon of murder after all. As Caproni said, "Flight is the beautiful dream and curse of mankind".

So what does Jiro Horekoshi think about this? In the film, while he is constantly aware of the impending war and occasionally expresses his disapproval of the military, Erlang doesn't seem particularly resistant to serving the needs of the military. This is rather subtle, given Miyazaki's long-standing anti-war stance. What the audience sees, Erlang, is a young engineer who is desperate to realize his airplane dream. Even though he was once the target of surveillance and oppression by "Super High" [Note 1], Erlang still worked hard to complete the task he was assigned.

Until the end of the movie, the dream is completed, but the achievement of the dream destroys the country. When he met Caproni again in the prairie in his dream, he said sadly, "I fulfilled my dream, but I was exhausted... None of them (the pilots of "Zero War") came back... ." At this time, Jiro Horetsu seemed to really face the war and the contradictions of his dream. However, through Nahoko's (supposedly dead) call to "live", Jiro regained the power to live.

Here, Hayao Miyazaki seems to imply that personal dreams and the pursuit of personal meaning can transcend the pull of the real environment and external forces: even if the plane eventually became a killing weapon, Erlang still built a beautiful plane. But is this an excuse for Jiro Horetsu's "war responsibility"? A large part of the criticism that "The Wind Rises" received in Japan came from such places. Critics mostly think Miyazaki's attitude towards war is too ambiguous, and he lacks criticism of Jiro Horetsu's identity as a murder weapon maker. In other words, these critics believe that The Wind Rises lacks the critical spirit of history.

I think Hayao Miyazaki really looked at Jiro Horekoshi from the perspective of "sympathy and understanding", and looked at the fact that his plane "destroyed the country" with tolerance. But I also think that Miyazaki isn't just trying to celebrate Horetsu's achievements in building an airplane and fulfilling his dreams. He wanted to discuss something deeper.

--Hori Tatsuo and "The Wind Rises"

To understand Hayao Miyazaki's thoughts, one has to mention Hori Tatsuo's "The Wind Rises". This novella is about a young man who accompanies his fiancée, who has contracted tuberculosis, to a sanatorium on the plateau to recuperate. This story is based on his own experience. Hori himself is a patient with tuberculosis, and his fiancee, Yano Ayako, also suffers from tuberculosis. [Note 2] In the second year after the two got engaged, Ayako went to a tuberculosis hospital in the mountains for treatment and died in the winter of the same year. Hori wrote "The Wind Rises" based on this experience. [Note 3]

The novel "Wind Up" describes how "I" and "Setsuko" get along. Although "I" is immersed in the happiness of living with "Setsuko" in the story, and feels the joy and beauty of love and life with "Setsuko", but also constantly aware of the approaching death. So "I" decided to write a novel to tell the story of myself and "Setsuko":

"I want to write a novel about you, but I can't think of anything else. The happiness we give to each other now - from the world Thinking that there is no way out, the joy of life germinates - I want to convert this feeling that no one knows and only belongs to us into a specific novel, okay?"

But when he began to conceive the plot of the novel, "I" Instead, she finds herself having to face the possible outcome of her lover's death. "I" imagined that the heroine of the novel would die at the end, and thanked the hero for bringing her happiness before her death, and this cheered the hero up and believed in the little happiness between the two. Thinking of this, "I" can't help but feel a mixture of shame and guilt and fear towards "Setsuko". "I" hopes that by writing novels, both himself and "Setsuko" can affirm the happy times that the two have experienced, but he also constantly doubts whether he really understands the idea of "Setsuko"? Or is it that he is actually just imposing his own dream on "Setsuko"?

Setsuko is still dead. More than three years after the death of "Setsuko", "I" returned to the valley where "Setsuko" met for the winter. "I" kept thinking about the past with "Setsuko" and felt lonely and sad. But after reading Rainer Maria Rilke's "Requiem", "I" gradually accepted the death of "Setsuko", felt the beauty of life again, and was convinced that my love with "Setsuko" was real And meaningful:

"...Maybe my current state is closer to a kind of happiness. Or, it can be said that my mood is similar to happiness but a little more sad than happiness... But, Setsuko, I I've never blamed you for such a lonely life. I just do everything I like for myself. Maybe, although it's all for you, I'm completely used to thinking that I don't deserve your love for me. As for acknowledging that everything I do is for myself.”

So at this moment, “I” was finally redeemed and my passion for life was restored. Perhaps what Hori Chenxiong wanted to express was that after walking through the valley of death and disillusionment, those who survived still have to find the strength to move forward in the embers, and believe in the value of life. When the wind rises, the only way to survive is to work hard, and the meaning of survival revealed by Hori Tatsuo in his novels is love. So, how did Miyazaki digest and adapt Hori Tatsuo's story?

--"Only to survive"

Speaking of the romance of men, "trying to survive" has always been a major theme of Hayao Miyazaki's films. From "Nausicaa" to "Magic Princess", in some of his more serious works, Miyazaki often praises the protagonist for upholding a pure and persevering mind in a difficult environment, resisting the oppression of external forces and man-made folly. Even in "Red Pig", he affirmed a kind of life sentiment of common people surviving in the face of adversity through the optimistic life attitude of Mayfair and the big family of the Paocolo factory. In "The Wind Rises", the story of Erlang building a plane and his love with Nahoko are also two aspects of this proposition.

Nahoko may be the closest thing to a "dream lover" among the characters that Hayao Miyazaki has ever created. She had a "fateful encounter" with Erlang in the movie, and they reunited by chance many years later. The scene where the two met by the pool was a complete mess, and the wedding at Kurokawa's house blinded tens of thousands of people. The audience; she is frail and sickly, but she still firmly supports Erlang's dream until the end of her life... If there is a woman like this, what can a husband ask for? (laugh)

This kind of setting seems to be quite old-fashioned, with a rare "big man" atmosphere in Hayao Miyazaki's works. After Erlang and Nahoko got married, Erlang's sister Kayo visited and questioned why his brother kept the seriously ill Nahoko by his side. Erlang's answer was, "I know too... We cherish every day we spend together and live very happily." It sounds like a jerk! This kind of plot arrangement can probably be said to be a (stinky) man's romance, but Hayao Miyazaki's deep meaning is hidden in this place.

In the film, Nahoko goes from the sanatorium on the mountain to Nagoya alone, and the scene where she reunites with Erlang at the station is adapted from the plot of another novel "Nahoko" by Hori Tatsuo: the heroine who recuperates alone on the mountain runs back to Tokyo impulsively. He secretly hoped that the husband could speak to keep him; but the husband was worried about the attitude of the mother (who couldn't get along with the heroine), and could not understand why the heroine came back so impulsive. The disappointed heroine had to say that she would go back to the mountain alone the next day. Erlang's line in the movie "Don't go back, stay and live with me" is actually the line in the novel that the heroine expects her husband to speak. Miyazaki said these words through Jiro's mouth. [Note 4]

Apparently, Nahoko herself in the movie wanted to stay. Although Nahoko voluntarily went to the mountains to recuperate at the beginning, she eventually left the hospital resolutely and returned to Erlang. This decision may reflect how Nahoko sees the meaning of her life: going to the mountains is to survive, but more important than survival is to make her limited life full and beautiful. So Nahoko chose to pursue love and live with her lover, even at the expense of aggravating her illness. Here, the love between Nahoko and Erlang echoes the life attitude of "love" as the highest value revealed by Hori Tatsuo in the novel "The Wind Rises". That's why Erlang in the movie will calmly keep Nahoko, because only if Nahoko stays, the two of them can "work hard to survive" together through their love for each other. And the goal of this "strive to survive" is to let Erlang build a beautiful plane. Nahoko's love and Erlang's plane dream are two aspects of the same thing.

However, on the day that Erlang's plane was successfully tested, Nahoko quietly left. Kayo, who came to visit, was about to rush out the door to chase Nahoko back, but was discouraged by Mrs. Kurokawa; she said that Nahoko wanted "to let the person she loves see only the most beautiful moments in her life". Why does this somewhat tragic statement come from? I think another meaning of these words is that Nahoko believes that she has completed an important mission in life. When the beautiful plane soared in the sky, the wind also blew, and the lives of Nahoko and countless people seemed to fall with the wind. So the screen immediately turned to the dream grassland that turned into "hell", and Erlang met Caproni again. Erlang's sentence "I have completed my dream, but I am also exhausted" has a particularly moving and sad meaning. In addition to the demise of the country, does your dream also take away the meaning of life?

In the dream, countless "zero battles" slowly rose under Erlang's attention, and merged into the plane cloud river high in the sky. The same scene also appeared in "Porcupine": Pollock tells Mayfair about his near-death experience during the war, watching his best friend's plane float high into the sky. All his comrades died, only he survived. Polluk said a famous line here:

"The good people are those who have died. And who knows if the place they went to is hell?"

He is a "bad guy" who bears the lives of his comrades and opponents. Polluk in "Porcupine" feels guilty and suffers for it; in Miyazaki's writings, Erlang in "The Wind Rises" probably has a similar feeling. But Miyazaki finally provided a way out for his role: Polluk was redeemed by Fei'er's love and vitality; as for Jiro, he reaffirmed the meaning of his life in the call of Nahoko: whether it was the dream of building a plane Or the love for Nahoko, after all, has its meaning. And this belief also opens up new possibilities for the future life.

However, it is still necessary to return to the original question: what attitude does Hayao Miyazaki show to Japan's war of aggression in this story?

--Airplane Dream, Empire Dream and Mysterious Foreigner

In the movie, Erlang's airplane dream faces many external constraints: Japan's national strength is far less than that of advanced countries in Europe and the United States, and it is also seriously backward in technology. In this case, the only one with sufficient resources to support Erlang's aircraft construction is the military. The film uses a lot of space to describe the embarrassment of external conditions, and uses several scenes (migrant workers walking to the city along the railway, running citizens, little sisters who refuse Siberian cakes...) to imply Erlang The dream is to pay what a price to be realized. When Jiro mentioned about the little sisters to Honjo, Honjo sneered at Jiro's "hypocritical" sympathy, pointing out that the cost of the plan they participated in "enables children all over the country to eat tempura cover every day" Rice and Siberian Cakes". Miyazaki has made it clear that people like Erlang and Honjo are, to some extent, responsible for the situation of these poor people.

However, Honjo immediately admitted that even so, he still wanted to do this job and realize his dream of building an airplane; although Erlang did not say it explicitly, from the perspective of the subsequent plot, he obviously agreed with Honjo and continued to bury himself in his work. I think Hayao Miyazaki's idea is worth pondering. Of course he sympathizes with the situation of these ordinary people who have no name and no name in the big era, and although he seems to always praise Erlang's pursuit of dreams, he also clearly points out that Erlang if To pursue your dreams, you must bear these responsibilities to survive. And if you continue to push down along this line of thinking, Erlang's "war responsibility" will be very obvious.

To explore Miyazaki's true view of this history, we must talk about the mysterious foreigner Casttrop who appeared at the mountain hotel, eating cress and singing ballads. In terms of setting, Castrop is German, and from his elusive characteristics, quickly seeing Jiro's background, and the plot of being tracked by "Tigao" in the future, Miyazaki should be implying that this person is a spy. Such a setting is easily reminiscent of another famous figure in recent Japanese history: Richard Sorge.

Richard Sorge, a German-Russian half-blood, was influenced by communist ideology when he was young, joined the Communist International, and was absorbed by the Soviet intelligence agencies to collect intelligence for the Soviet authorities. Under the cover of a journalist and a member of the Nazi Party, he was active in East Asia all year round. In 1933, he established an espionage organization in Japan and collected many important information for the Soviet Union during World War II. His organization was busted by the Japanese in 1943, and he was executed the following year.

One night, Castrop came to talk to Erlang. Casttrop said:

"This is a 'magic mountain' far away from the mundane, where people will forget all the mundane things: the war with China, forget it; the affairs of Manchukuo, forget it; withdraw from the League of Nations, forget it ; Enemy the whole world, forget it."

The metaphor of "Magic Mountain" is quite interesting. The name "Castorp" (カストロプ) is actually taken from the hero of Thomasman's masterpiece "The Magic Mountain". By comparing the mountain hotel to a "magic mountain," Casttrop was also criticizing the Japanese at the time (and perhaps Jiro, too) for ignoring the looming war and the increasingly difficult situation. But what's interesting is that this Casttrop is also the promoter of Erlang and Nahoko's love affair, joining the two of them in the flash game (no mistake) of "you throw me and pick it up". He and Erlang and others obviously have a good friendship on that "Magic Mountain".

Sorge in history is considered to be an idealist, he dedicated himself to his ideal, attracted many Japanese to follow, and left many legends. In "The Wind Rises", Hayao Miyazaki clearly has a positive evaluation of Casttrop. Yet, despite his harsh criticism of the Japanese (especially the upper classes), Castrol seems to have respect for Jiro's ideals. Hayao Miyazaki used Castrop to criticize the history of Japan before the war, and I think to a certain extent he also acknowledged Jiro Horekoshi's "guilt", but at the same time he also regarded Horetsu as an idealist, and he was very concerned about his guilt. This aspect expresses affirmation.

Going back to a scene that appeared in "Porcupine Pig": the father of the Paocolo factory leads his employees in a pre-dinner prayer, praying that God will forgive them for "the sin of making weapons with women's hands", and then laughing loudly I want everyone to "eat a little more and work hard when you're full." Making weapons is sinful, but necessary to survive. This may also echo Erlang's hidden mentality in "The Wind Rises".

--The Fate of the Ideal Home and Hayao Miyazaki

In a translation of a Japanese film review that was reposted in the previous edition[Note 5], the critic criticized Hayao Miyazaki for seemingly advocating the image of a "lively big family", but on the surface he praised Caproni's large plane full of family and employees. What he really wanted was the "slim, ascetic" (and lonely) killing weapon "Zero War". I think this statement is only half right, basically Hayao Miyazaki has a lot to say about Hele's raucous "big family" (Grandma Dora and his sons in "Castle in the Sky", the women at the Poccolo Factory in "Porcupine", The Magical Princess" The Women of Dadala City...) does have a positive view. Subtly, in his works, the hero is often alone.

At the end of "Porcupine", Pollock beats Cadiz, but he still refuses Mayfair's love, throws Mayfair on Gina's plane, and asks Gina to "bring this child back to a normal person. world". Pollock's meaning is clear: he's going on an "abnormal" and dangerous path, and he doesn't want to involve Mayfair (and Gina) in it. In other words, if you really want to carry your dreams, people are bound to take a lonely road. Therefore, rather than saying that Erlang's concept in "The Wind Rises" is opposed to Caproni, it is better to say that Erlang's pursuit of ideals was originally lonely.

Of course, Miyazaki arranged a love affair with Nahoko for Erlang of "The Wind Rises", and depicted the process of the two supporting each other in pursuit of their ideals in an extremely beautiful and moving way, but Nahoko died after all. I believe that to a certain extent, Nahoko's death can also be seen as one of the prices Erlang paid for realizing his dream. At the end of the film, Erlang faced Caproni's question of "whether he has lived the past ten years seriously", and admitted wearily that although he did his best to fulfill his dream, "he was exhausted." The "mental exhaustion" here, in addition to witnessing the disillusionment of the dream, naturally also includes the guilt towards Nahoko.

I think what Miyazaki is revealing here is his own attitude to life. Although Miyazaki appreciates the sincere emotions and "big family" relationships between people, he implicitly reminds him that this is not the path he has taken in his life. From "Red Pig" to "The Wind Rises", Polluk and Erlang both choose to practice their own life meanings and ideals, and embark on their own life journeys alone. Although Nahoko, who was still alive, asked Erlang to "live", he turned into a phantom and disappeared. The remaining Erlang, after drinking red wine with Caproni, still has more than half of his life to spend, waiting for a hundred years later. Nahoko's reunion in another world..."Survival" is not just about simply living, but also about continuing to struggle to find new meanings for the unfinished life journey.

I believe this is the most important message Miyazaki has brought to the audience, and it is also Miyazaki's summary of his career. "Porcupine" also has a famous scene: Polluk, who was shot down by Cadiz, called the distraught Gina, who asked Polluk to give up his dangerous flying career on the phone:

"Horse But, you will become a suckling pig one day. I don't want it, I don't want this ending."

"A pig that can't fly is a useless pig."

"Idiot!

" I don't know what else I can do and what to do other than flying. But even so he could only fly down, rather than into Gina's garden. Twenty years have passed since "Porcupine" and "The Wind Rises", and Hayao Miyazaki has never stopped his creation. In other words, Miyazaki didn't want to be that "useless pig" either. Twenty years later, this flying pig has finally reached his destination. "My ten years are over," and Miyazaki has no doubt, in his "ten years," exerted all his strength and accomplished great things. In this sense, "The Wind Rises" is Miyazaki's well-deserved masterpiece.

Since its release, "The Wind Rises" has attracted a lot of criticism and incomprehension; it is a work that is not very "Miyazaki", with many subtle and incomprehensible fragments, and it is not so entertaining. But in my private opinion, this film is undoubtedly one of Miyazaki's greatest works of his Ghibli period. He devoted his life to this work, and at the end of his career tells a story that belongs to him and reflects his spirit, care and life course. "Wind Up" will inevitably fail to achieve the box office and award-winning achievements of "The Hidden Girl", but the value of this film is difficult to replace and ignore.

[Note 1] "Extra High", the full name of "Special High Police", was the secret police of Japan before the war.

[Note 2] Karuizawa is the stage for many of Hori Tatsuo's works. He has been staying in Karuizawa since his youth due to lung disease. He also met and fell in love with Yano Ayako in Karuizawa. However, the mountain hotel where Erlang and Nahoko fell in love in the movie "The Wind Rises" is set in Karuizawa.

【Note 3】Hori Chenxiong's creation and life can be seen from Lai Mingzhu's introduction article for the Chinese translation of the novel "Wind Up".

http://news.msn.com.tw/news3339916.aspx

[Note 4] I haven't read "Nai Suiko" myself, but I learned this allusion from Liu Li'er's interview with Hayao Miyazaki. Liu's interview article can be found at :

http://news.chinatimes.com/reading/11051301/112013091600043.html

http://news.chinatimes.com/reading/11051301/112013091700047.html

Not Flying Against Gravity - "The Wind Rises" Film Review>

http://blog.livedoor.jp/aarinoshitw/archives/31959036.html

View more about The Wind Rises reviews