Abstract The animation "Mima's Room" directed by Jin Min is a text very worth studying. In this paper, the author introduces the second film semiotic theory and psychoanalytic theory to interpret the film, focusing on the relationship between vision and desire that the film presents to the audience, as well as the film's "growth" theme And the "mirror" constructed by the medium of animation.

Keyword Animation Text Mima's Room Psychoanalysis Film Semiotics

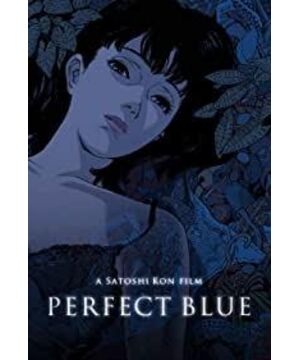

The Japanese animation master Toshi Kon, who died young, used his animation director career for more than ten years to bring to the audience one classic in the history of animation. The animations directed by Jin Min have distinct personal characteristics. The overlapping of dreams and reality and the sensitive nerves of human beings have become the common themes in Jin Min's many works. "The Room of Wei Ma" (Perfect Blue, a translation of "Perfect Blue", hereinafter referred to as "Wei", 1997) is the first animated film directed by Jin Min, and it is also the high-quality film that I think can best represent Jin Min's creative ideas. work. It is a typical text about seeing and being seen. It is a profound discussion of vision and desire. It has led to a large number of topics in psychology, especially psychoanalysis, and it is worth reading carefully.

Vision is about desire: The stared

Mima is from the core member of the idol singer group CHAM. Under the arrangement of the office, the young girl Kirigoshi Mima had to go solo and start her own acting career. What awaited her was a completely different life. The pressure of the new job, the disappointment and doubts of the former fans, and the threats and threats one after another... All these make Wei Ma anxious. In order not to cause trouble to anyone, Mima reluctantly agreed to appear in the large-scale drama of being raped, and took a nude photo shortly after. What followed was the murder of the screenwriters and photographers who worked with Weima, and the gradual breakdown of Weima's spirit.

Wei Ma is the protagonist of "Wei". She is still young and just an ordinary little artist. In the past few years, as an idol singer, she lived a simple life and often squeezed the subway to get off work alone. At that time, computers were not yet widespread, and Wei Ma had no understanding of the Internet at all. Under the guidance of the agent who stayed in the United States, Weima learned to use the Internet initially, and began to pay attention to the website named "Weima's Room". She realized that the recorder was writing down her daily life in great detail, and she began to feel inexplicable anxiety.

Under the domination of the modern visual industry, we can expand the sources of content to be viewed through various media such as television, magazines, and the Internet—as McLuhan pointed out, television, cameras, websites... are all of us Extension of the eye. As a result, every move of the star Weima has attracted everyone's attention. And this relationship between watching and being watched is multiple and rich, because Weima's fans, movie fans, collaborators, and all those who pay attention to Weima, and even us as the audience of the movie "Wei", have become to the viewers of Wei Ma.

In this way, Mima was exposed to the spotlight and the camera from beginning to end, and was in a position to be seen. "Weima's Room" as the name of the fan/fan website reflects that Weima's life is openly and openly presented - visitors to the site can peek into the details of Weima's life here. This website has become an important symbol of Wei Ma's "being seen" in the public eye. At the same time, Weima's own room is a recurring scene in the film, which symbolizes Weima's heart: when Weima is nervous and almost out of control, the room is messed up under her madness. This shows how appropriate the title of this film is "The Room of Weima".

Wei analyzes the relationship between vision and desire. At this point, we will naturally think of psychoanalytic film theory. The theoretical foundation is derived from Lacan's psychoanalytic theory, and the second film semiotics believes that the eye is an organ of desire, and the viewer can obtain pleasure and desire satisfaction from the act of watching. In the text of "Wei", there is a shot combination that can be called a classic that binds desire to vision. When Wei Ma was filming the rape scene, a camera on the set was panned up, cut to the stalker's shot, and then to a close-up of Wei Ma's body, where the camera was periodically panned downward. The "pan-up" here is a metaphor for the erection of the male genitals - something Jin Min alluded to in an interview a few years after the release of "Wei". Later, the sequence of scenes showing Mima (actually her role as Yoko Takakura) showing off her body accompanied by loud music makes Mima's stare/desire object very clear.

Weima's career transformation can be said to be forced under the arrangement of the office, and this rape scene undoubtedly means the forced termination of Weima's career as a singer, which is the destruction of the former girl idol status. During the filming of this scene, Weima, who was lying on his back on the dance floor, stared at the lights on the ceiling with dark eyes. At the end of the paragraph, we flashed back to Weima's confident smile as a singer facing the countless audience under the stage. Turned into a white field - this symbolizes the death of Mima, who was a singer in the past. Jin Min once said that after the filming of this scene, Weima was sitting in the dressing room wearing black clothes like mourning clothes. This is Weima's mourning for the singer who no longer exists.

Recalling what feminist film criticism pointed out, the female images that appear in mainstream commercial films only serve as visual motives that constitute a spectacle and trigger the desire to watch (Dai Jinhua. Film Criticism [M]. Beijing: Peking University Press, 2004, p. 123 Page), we can clearly see that Wei directly, even cruelly, displays this attribute of Weima, offering deep sympathy for Weima as a weak woman and as the focus of the visual spectacle of the mass media.

The company's Mr. Tiansuo drives Mima home from the set. Wei Ma saw the tropical fish she raised die in large areas, and this episode became another footnote to "Once Wei Ma is dead". Wei Ma burst into tears in her room, messing up her room out of control, just like her chaotic heart. Only two small fish remained in the tank. Jin Min hopes to imply the contradictory state of "two unma" with the survival competition relationship between the two fish. Interestingly, film semiotician Metz has used a similar metaphor to describe the relationship between actors and audiences: he believes that actors and scenes in filming are placed in an aquarium-like space. The space is relatively closed, surrounded by transparent glass walls on all sides, with numerous staring eyes outside the walls. (Dai Jinhua. Film Criticism [M]. Beijing: Peking University Press, 2004, p. 161)

Wei Ma's Phantom in the Mirror: The Inner Force of Three People

As a suspense animated film, the core suspense of "Wei" is who has the identity of a criminal. It is not difficult to find that the unresolved mystery of "who is the murderer" is always guided by the details of the film, which is the film's narrative strategy. The first half of "Wei" "deceptively" suggested that the stalker was the murderer. His extremely ugly face left the audience with the first impression of "this person is full of danger". In the second half of the film, it seems that all signs point to Weima again. When describing Weima's dream, the film even directly shows the bloody scene of Weima killing the photographer.

The suspense drama Double Bind (hereinafter referred to as DB), which Wei Ma participated in, is the "play within the play" of "Wei". It serves as a thread parallel to the main plot in the film, and becomes a series of sidenotes to the main line. Mima plays Yoko Takakura, the younger sister of the murdered. Yoko's first line in the play, "Who are you?" has become a question throughout—who is the criminal who harassed Mima and killed several lives one after another. It wasn't until near the end that the mystery was revealed: the murderer - also a person with split personality - was Wei Ma's agent who stayed in the United States.

Wei Ma, Liu Mei and Stalker are the three characters that are mainly portrayed in Wei. In addition to their intuitive "artist-manager-fan" relationship, there is also an implicit link connecting the three: Wei Ma's phantom in the mirror. This phantom keeps appearing in the building windows, car windows and mirrors that Wei Ma passes by, and is regarded as the "imaginary singer Wei Ma" who is fighting against his heart. Yoko in DB faces the danger of split personality, and Dr. Hitomi persuades her to feel at ease, because "fantasy will not become reality". But in reality, Wei Ma has begun to worry about whether the other self really exists. The film repeats footage of Weima waking up from her bed multiple times, a rhetorical twist that distorts the film’s timeline, showing that Weima’s struggle against Wei Ma is influenced by the “Weima Room” website, intimidation and murder, and struggles with fear. Reality and dreams are indistinguishable. The phantom tortured herself again and again, and she even had to use the retelling of the recorder on the website to recall some of her memories.

On the surface, the phantom shows the fantasy of Weima alone. In this way, the film narrative presents Weima's mental activities that he is afraid to look directly at himself and find it difficult to face himself; but in fact it is not only that - this "Weima in the Mirror" is shared by Weima, Liumei, and Stalker, and is the product of their common fantasy.

First of all, for Wei Ma herself, this imaginary she appears in various mirrors in most cases - which reminds us naturally of Lacan's classic discussion of mirroring. Lacan believes that the mirror image is an "ideal self", or an imaginary self, of the infant before contact with society. The experience of this self in the mirror forms the imaginary world. After this stage, he or she will complete his or her life. Growth and transformation for the first time. (See: Lu Yang. Psychoanalytical Literary Theory [M]. Shandong: Shandong Education Press, 2005, pp. 152-154) In this sense, Wei seems to have reproduced in Wei Ma’s body In this "imaginary world", although the self in the mirror does not belong to an infant but to a young girl, the contradiction between Wei Ma is the contradiction between the "imaginary self" and the "real self". Just as Wei Ma in the film grew from a naive idol girl to a calm and independent actress, "growth" is an important theme of "Wei".

The second is Wei Ma in the stalker's fantasy. The Stalker appears as a mysterious character throughout the first half of the film. During the day, he appeared as a security guard in the concert audience area and around the DB studio, often watching Wei Ma's every move in the corner. The essence of a stalker is a gazer, and he is the representative subject of all "watching behaviors" of Weima. He manages the content of the website "Room of Unma", where everything is the result of stalkers' prying eyes. At the same time, he is the representative of the pathological fetishist. Weima posters large and small were placed in the stalker's dark, cramped room; he even bought all the magazines he could buy that printed Weima's nude photos—these were "evidence" of the fetish. It has to be said that the mass production of products by Star Industry is also a culture of "producing" fetishes, which is a profound reflection of "Wei".

The stalker wrote the website log in Wei Ma's tone, apparently imagining himself as a singer Wei Ma describing his daily life - psychologically speaking, this is a typical behavior under identification. This is reinforced by the film's depiction of the stalker typing in front of the computer while silently reading the website logs. Immediately afterwards, the picture cuts to his back: this is an almost symmetrical shot in the horizontal direction, and the back divided into two in the composition is suggesting the differentiation of his personality.

If the stalker's behavior is simply out of the love of a fanatical fan (the deeper reasons are not explained in the film), then the motivation for staying in the United States is rooted in his former singer experience. In "Wei", it is clearly stated that studying in the United States is an idol singer who has worked hard but was unsuccessful. This identity is an important reason for her to care about Wei Ma. The female agent who cares about her the most around Weima and regards Weima as her hope has witnessed Weima growing up all the way, unable to accept such a huge change in her in a short period of time. Under the sadness, she becomes mentally disturbed and splits into a new personality - as a Singer's Wei Ma - completed the psychological defense mechanism of analogy. This new U.S./fake Weima even carefully copied Weima's room in her own residence.

Liu Mei established an email connection with the stalker as a "real Wei Ma", which led the stalker to think that the actor Wei Ma was a fake. As a result, the phantoms in the hearts of Mima, Rumi, and Stalker overlapped. As an important reminder from DB: Doctor Hitomi in the play once believed that Yoko's split fantasy was "projected" onto a real person, or that someone materialized this fantasy, so Yoko would think that he It is really a criminal; in reality, it is the split personalities of staying in the United States that materialize the "shared phantom" projected by the three people. This group of subtle special character relationships is thus structured.

In the end, the explanation for the ending ended

up in the United States and was admitted to a mental hospital. At the end of the film, Wei Ma went to a mental hospital, which is not called a visit, but just watched studying in the United States through the glass. She said to the doctor, "I know I can't see her anymore, but it is because of her that I am who I am today." The "she" here refers not only to staying in the United States who took care of her in the past, but also to the singer who used to be an idol singer. Herself. The "look" through the window here echoes to a certain extent the metaphor of the fish and the fish tank we discussed earlier, and it shows that Wei Ma is finally able (even temporarily) from a fish that is stared at like a fish in a tank. Freed from desire objects and passive identities.

She got into the sedan after leaving and looked at herself in the car mirror. The last shot of the whole film is a close-up of Wei Ma's face in the mirror. She smiled and said to herself, "I am the real (Weima)." The author believes that this smiling mirror symbolizes Weima today, Weima who was a young actor in the past, and Weima, an idol singer in fantasy. The unity of the three shows that Wei Ma's growth has been completed, and she has been able to see herself clearly and objectively, without having contradictory assumptions.

Jin Min's own explanation is quite interesting. He emphasized in the interview that the use of mirror images here is to imply to the audience that Wei Ma's growth is not complete maturity. Perhaps we can say that every time we become aware of our own growth, we are judged by "the self in the mirror". Jin Min believes that Wei Ma's growth is bound to be an iterative process. The story has not really ended yet. Wei Ma may even have doubts that she is "true", and a complete Wei Ma has not yet formed.

In the following words,

this is an animation text criticism article, and it is also the author's first attempt to study objective and professional animation film criticism. The theory of animation is not yet sound, so film science has always been a frame of reference and benchmark for animation. However, domestic animation scholars often stop at the theoretical crystallization before the 1960s in their reference and study of film studies, but turn a blind eye to the modern film aesthetics and criticism theories that started from film semiotics. This is one of the important reasons why the theoretical construction of animation has always been in a passive and backward state. In fact, modern film criticism is exactly what we use to analyze mainstream narrative animation. It helps us move away from the "emotionally expressive" animated film reviews that have become commonplace, while avoiding over-interpretation of the film through evidence-based discovery and analysis.

In addition, critics of animation works should also discover the characteristics of the works that are different from the real-shot images, because animation and real-shot images use different visual symbol systems, and have different modeling and movement mechanisms (for this, the author will use it in future articles. extensive details). In Wei, the media characteristics of animation are concentrated in the creation of Wei Ma's "mirror". As Krakauer pointed out, the essence of live-action images is the restoration of physical reality and the faithful recording of actions. Therefore, the imaginary Mima's phantom is difficult to present in real shots. In contrast, through the medium of animation, two real and fake Weima can simultaneously appear in the audience's viewing field of view in the same shot - this is obviously better than the use of montages and stand-ins for live images. It is more direct, shocking and credible for actors or CG special effects to "make up for the poor". The many fierce disputes and chases between the two Weima in the film, as well as the transformation from "fake Weima" to staying in the United States, all show the advantages of animation. In short, it is the animation medium that enables the "mirror" of "Wei" to be established.

References

[1] Dai Jinhua. Film criticism [M]. Beijing: Peking University Press, 2004.

[2] Christian Metz, etc. The pleasure of gaze: Psychoanalysis of film texts [M]. Wu Qiong, ed. Beijing: Renmin University of China Press, 2005.

[3] Lu Yang. Psychoanalytic Theory [M]. Shandong: Shandong Education Press, 2005.

[4] Christian · Metz. The imaginary signifier [M]. Wang Zhimin, translated. Beijing: China Radio and Television Press, 2006.

http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_4c39969f0101ksnz.html

(Original published in the December 2012 issue of "Culture Monthly Anime Games", with major revisions.)

View more about Perfect Blue reviews