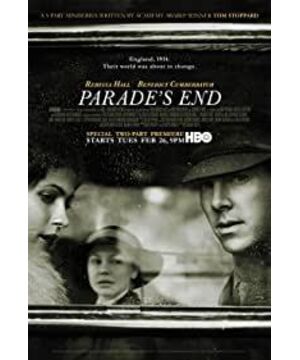

It would be easy, then, to glance at the particulars of "Parade's End"—a five-part interpretation of Ford Madox Ford's four-novel omnibus of the same name, which makes its American début on HBO on Tuesday night and runs through Thursday —and see it as simply another polite addition to the genre. Set in the waning years of Edwardian England, it tells the story of Christopher Tietjens, a solid Tory and the heir to massive estate, who endures a fraught marriage with his unfaithful and alluringly venomous wife, Sylvia, while denying himself love and happiness with a young woman called Valentine Wannop. In relief, it is a familiar arrangement: a passion-filled love triangle across class lines paired with the eat-your-vegetables-too history lessons of the suffragette movement, the decline of Victorian mores, and the rise of the First World War.

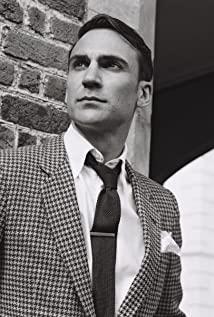

Yet, this adaptation of “Parade's End,” with a screenplay written by Tom Stoppard, aims to be more than a faintly intellectual delivery device for romance. It retains much of the most striking, caustic, and funny dialogue from Ford's novels, and Stoppard's additions evoke the spirit and cadence of the source material, as when Sylvia, in decrying her husband's oppressive goodness, sneers, "You're such a paragon of honorable behavior, Christopher. You're the cruellest man I know." And the principal actors capture, in quick and sure ways, the essential qualities of their characters. Benedict Cumberbatch, as Tietjens, pairs fiery, resolute eyes with a wobbly chin, at once conveying the assuredness and fear of an “eighteenth-century man” born two hundred years too late—a man confident in his values,and equally confident that those values no longer hold sway. When he declares, “I’m for monogamy and chastity and for not talking about it,” he seems rather like a cocksure boy saying the lines of an older man, and this is just right: the essential contradiction of Tietjens's character is this bluster about honor mixed with his own very real sense that he is wrong about most things and has made a mess of life. Julian Barnes describes Tietjens as inhabiting an “inept saintliness,” and, indeed, , he is a loveable, and rather willing, martyr.the essential contradiction of Tietjens's character is this bluster about honor mixed with his own very real sense that he is wrong about most things and has made a mess of life. Julian Barnes describes Tietjens as inhabiting an “inept saintliness,” and, indeed, he is a loveable, and rather willing, martyr.the essential contradiction of Tietjens's character is this bluster about honor mixed with his own very real sense that he is wrong about most things and has made a mess of life. Julian Barnes describes Tietjens as inhabiting an “inept saintliness,” and, indeed, he is a loveable, and rather willing, martyr.

Rebecca Hall plays a delightful Sylvia, wicked and hateful and magnetic—attracting and repelling her husband, her various lovers, and the audience as well. Ford gave most of the best lines to Sylvia in the novel, and the same holds here, to great effect. Adelaide Clemens, as the young suffragette Valentine Wannop, may appear a bit less vigorous and sporty than we know her from the novels, but her open-faced radiance and easy, modern humor make her not just an appealing character but also an antidote to the stodgy folk around her. She also gives the best, and most diagnostic, line in the series, when she tells Tietjens, “I thought your type were all in museums. You want to be an English country gentleman spinning principles out of quaintness and letting the country go to hell. You won't stir a finger except to say I told you so.”

The whole of the “Parade's End” series is first-rate: the hats, the coats, the dresses, and the furniture all look right. The existential and practical nonsense of the First World War comes clearly through—its cruel waste of human energy and life. The trenches of France are black and gray and brown and terrifying; the fields of the Kent countryside are variously yellow or green, and soothing. It is a finely done adaptation in nearly every respect. And, yet—and partisans of a novel always seem to sigh and say “and yet” at this point in discussing a book-to-screen adaptation—there is something missing from “Parade’s End,” something more than just the natural narrative elisions and reworkings that a new medium requires.

I suspect that viewers who have not read the novels will reach the end of the series feeling as if they have spent a charming time in the company of appealing but ultimately odd and inscrutable characters. Tietjens, Sylvia, and Valentine are not conventional romantic players— their desires are obtuse and unusual and hard to figure, and the ends they meet are vague. It is as if the connective tissue has been removed—which, of course, it has. Not the tissue of plot or character but of overarching purpose, and of voice—or more simply and most obviously, of words. In the transition from page to screen, “Parade's End” retains its components but has lost, inevitably, its animating spirit, which is Ford's prose: both his archaic and gloriously obscure diction, which represents a form of literary Toryism, beholden to the past;and his high modernist stream-of-consciousness style, which points boldly to the future.

This loss, though, is only natural, and is endemic to the literature-based miniseries. Tom Stoppard explained his process of writing “Parade's End” in an interview with the Telegraph,

I've never had any interest in trying to impress an audience with my ability to juggle time and space in an intriguing, modernistic way…. Whatever you're doing, you always want a script to be a page-turner. It's very important never, ever, to feel above that.

Stoppard said the same thing last year about his screenplay for the movie adaptation of “Anna Karenina,” and further explained that in order to get Tolstoy's novel into manageable shape, he chose to focus on every point in the narrative that concerns the word “love .” This may be a showy bit of populism, but Stoppard surely knows a thing or two about entertaining an audience, and here he is correct: when turning a sprawling novel into a two-hour cinematic romance, the word “love” is, Indeed, the operative one. And so, too, with “Parade's End”: in order to make a mostly linear love story, much from Ford's novels has to go. The most significant alteration is the nearly complete removal of the fourth and final novel in the series, “Last Post,” which is the most abstract, the most difficult and maddening,and contains the least amount of action (the main character, Tietjens, appears hardly at all). It was also the most polarizing among critics and readers; Graham Greene hated it. But even with the final novel dispatched, Ford's “Parade's End” is no page-turner. It wasn't mean to be, and so it suffers in a hurried-along state, leading to the muddled notions of characterization and motive that viewers may take from the miniseries. Why do these people do what they do? Why is Tietjens so fixated on decorum and so devoted to preventing his own happiness? Why is Sylvia so dedicated to wounding her husband? Why does Valentine, a modern and progressive young woman, fall devotedly in love with an older, married reactionary? (A tender scene in the fog, though beautiful, is not enough to explain it.)It was also the most polarizing among critics and readers; Graham Greene hated it. But even with the final novel dispatched, Ford's “Parade's End” is no page-turner. It wasn't mean to be, and so it suffers in a hurried -along state, leading to the muddled notions of characterization and motive that viewers may take from the miniseries. Why do these people do what they do? Why is Tietjens so fixated on decorum and so devoted to preventing his own happiness? Why is Sylvia so dedicated to wounding her husband? Why does Valentine, a modern and progressive young woman, fall devotedly in love with an older, married reactionary? (A tender scene in the fog, though beautiful, is not enough to explain it.)It was also the most polarizing among critics and readers; Graham Greene hated it. But even with the final novel dispatched, Ford's “Parade's End” is no page-turner. It wasn't mean to be, and so it suffers in a hurried -along state, leading to the muddled notions of characterization and motive that viewers may take from the miniseries. Why do these people do what they do? Why is Tietjens so fixated on decorum and so devoted to preventing his own happiness? Why is Sylvia so dedicated to wounding her husband? Why does Valentine, a modern and progressive young woman, fall devotedly in love with an older, married reactionary? (A tender scene in the fog, though beautiful, is not enough to explain it.)It wasn't mean to be, and so it suffers in a hurried-along state, leading to the muddled notions of characterization and motive that viewers may take from the miniseries. Why do these people do what they do? Why is Tietjens so fixated on decorum and so devoted to preventing his own happiness? Why is Sylvia so dedicated to wounding her husband? Why does Valentine, a modern and progressive young woman, fall devotedly in love with an older, married reactionary? (A tender scene in the fog , though beautiful, is not enough to explain it.)It wasn't mean to be, and so it suffers in a hurried-along state, leading to the muddled notions of characterization and motive that viewers may take from the miniseries. Why do these people do what they do? Why is Tietjens so fixated on decorum and so devoted to preventing his own happiness? Why is Sylvia so dedicated to wounding her husband? Why does Valentine, a modern and progressive young woman, fall devotedly in love with an older, married reactionary? (A tender scene in the fog , though beautiful, is not enough to explain it.)Why do these people do what they do? Why is Tietjens so fixated on decorum and so devoted to preventing his own happiness? Why is Sylvia so dedicated to wounding her husband? Why does Valentine, a modern and progressive young woman, fall devotedly in love with an older, married reactionary? (A tender scene in the fog, though beautiful, is not enough to explain it.)Why do these people do what they do? Why is Tietjens so fixated on decorum and so devoted to preventing his own happiness? Why is Sylvia so dedicated to wounding her husband? Why does Valentine, a modern and progressive young woman, fall devotedly in love with an older, married reactionary? (A tender scene in the fog, though beautiful, is not enough to explain it.)

In the novels, the tools of fiction provide these answers: third-person narration, rich description, and inventive and dense interior monologue, which often takes the form of spiralling stream of consciousness. These tools are mostly unavailable to the screenwriter, or, when attempted onscreen, often lead to bad ends—cloying narration, excessive monologues, and visual gimmicks that strive to gin up a feeling of disorientation. Stoppard and the director, Susanna White, wisely avoid them, save for a few flashbacks and a couple scenes of hallucination in the trenches. (The opening credits appear as filmed through a prism, which is about as showy as White gets.) From this flattening out, however, we get a high-modernist novel streamlined into pleasant and visually engaging entertainment. Singular characters in the novel, marked by depth and complexity,are merely attractive and clever and quick, with some nice bon mots, onscreen. Add lush visuals and a persistent score, and you've got the makings of drama, but of an entirely different sort than Ford created. Stoppard summed up the challenge of this adaptation in his interview with the Telegraph: "I did have to unravel it all, and also invent a lot, as the book doesn't actually provide the action that five hours of television require." To which, one might wonder, why turn "Parade's End," apparently drama-less and in need of punching up, into a miniseries at all?Stoppard summed up the challenge of this adaptation in his interview with the Telegraph: "I did have to unravel it all, and also invent a lot, as the book doesn't actually provide the action that five hours of television require." To which , one might wonder, why turn "Parade's End," apparently drama-less and in need of punching up, into a miniseries at all?Stoppard summed up the challenge of this adaptation in his interview with the Telegraph: "I did have to unravel it all, and also invent a lot, as the book doesn't actually provide the action that five hours of television require." To which , one might wonder, why turn "Parade's End," apparently drama-less and in need of punching up, into a miniseries at all?

The simplest answer is probably two words: “Downton Abbey.” But a better question might be, Why do so many novels get adapted into screenplays at all, when their essential quality, the persuasive and enthralling power of prose, always must be stripped— and the final product is left in some state of diminishment?

It's not clear if there are more adaptations these days, across all forms of art and entertainment, or if it just seems that way. Certainly, a look at popular cinema confirms their ubiquity: you have to go all the way down to number sixteen on the list of last year's top-grossing films (“Django Unchained”) to find a movie not part of an ongoing series (“The Avengers,” “The Dark Knight Rises”) or adapted from a book (“The Hunger Games,” “The Hobbit”). In terms of the movie business, the equation is a financial one, and it is pretty straightforward: making films is time-consuming, expensive, and risky, and the best way to cut some of that risk is to start with an “established commodity” with a built-in audience sure to fill the seats. A similar calculation exists in the publishing world,where adaptation and brand extension are the surest bets for authors and publishers. Novels become movies, or sometimes they become Broadway musicals and then movies. But, increasingly, novels become other novels. The results of these transmogrifications are most often banal or repetitive or psychically distressing: another bondage-and-submission best-seller or Jane Austen novel told from the perspective of the sensitive zombie that lived in the basement. Fan-fiction is nothing new, though; the authors of the Gospels were perhaps the first men to make names for themselves by reinterpreting a classic story. Many modern reimaginings of older works, meanwhile, have become essential: Jean Rhys's “Wide Sargasso Sea” is a kind of fan fiction, after all. So is “The Last Temptation of Christ.” And so on.It might be said that all narrative art is adaptation—there are only so many stories, and we are left to retell them on down the years.

Still, there is surely something lost, for creators and consumers, in an artistic landscape in which the only marketable products are variations on work created in the past. If the BBC, which broadcast “Parade's End” in the UK last year, and HBO were looking for a First World War drama to compete with “Downton,” why strain to wrangle Ford Madox Ford's complex novels into television shape? Why not commission an entirely original miniseries, with characters and a narrative that, though set in the past, are shaped by the contemporary influences of its creators? A work of art need not be set in the present to reflect the values and cataclysms and possibilities of its time—it is the interplay between past and present that changes how we see both. The novels that make up “Parade's End,” after all, were already “historical” when they were published,between 1924 and 1928, and were defined as much by the artistic and cultural changes that had taken place in the years since the War—the rise of modernism and the further dissolution of old class prerogatives—as they were by their vision of the past. By constantly reworking and recycling established works, we may remain trapped, like Christopher Tietjens, living in the wrong century.

View more about Parade's End reviews