The movie was not difficult to understand, but after seeing the bizarre ending at the airport at the end, I decided to find the original book for comparison - the result is still in line with my original judgment, but this judgment is revealed in the novel. More thorough, and thus more nihilistic, and with it, a somewhat fooled feeling, but still to give this wonderful intellectual game a knowing smile without any irritation.

Although it has the "gimmick" of a reasoning/suspense/detective genre film, it clarifies the logic of the story, stripping off Turing, Del Ferma, Woolf De Quincy and even "Alice in Wonderland" that adorn it. Wait, etc. colorful decorative paintings, this is obviously a novel with postmodern characteristics, which is anti-reasoning in a way of reasoning. Apart from the first deliberate murder, there is no crime in the whole story, let alone the so-called "serial murder". The deaths one after another were just one weird coincidence after another, and Professor Selden just used these coincidences to try to exonerate his daughter. To put it bluntly, it's that simple.

So, why does the author create such a narrative that ends up being busy? Is it to make readers laugh as Kant said, "full of anticipation turns into nothingness"? Or did he dig too big a hole and just give up? It would be too perfunctory to attribute all the murders that have paved the way for the truth to be revealed as coincidences?

of course not. This is what the novel wants, to keep all the wonderful reasoning idle to prove the unreliability of the reasoning, and to end the nest of mystery novels in the most extreme way. The magician didn't intend to conjure the rabbit out of the top hat, but took the top hat apart so you can see it clearly.

So - although like many postmodern novels it maintains a bewildering intertextuality with various texts - it comes back to this man: Wittgenstein. This precocious and arrogant genius claimed in the Treatise on Logic and Philosophy that he had solved all philosophical problems: speak if you can, and keep silent if you can't. But what's even more weird about the genius is that after more than ten years, he gave himself a loud slap in the face and dedicated a greater wisdom. In Philosophical Research, he revised his previous view of language in TLP: no longer regard language and logic as the only clear, stable, essential truth about the world. Language is still talking about people, about the world, and the basic conditions that enable people to think and understand the world, but Wittgenstein has stopped looking at language from an essentialist perspective, and even no longer essentially traces any chicken-and-egg Raw chicken people talk about people and other issues. One thing is clear: language is a game with a set of rules, and meaning is the use of language according to the rules. In other words, we think and speak in this way because our language has installed an operating system for the mind, and we are simply producing endless content within the constraints of this system. And things, or the world, could have been otherwise.

Wittgenstein's propositions about language are of course equally applicable to mathematics, and even crazier. For example, our language roughly divides a continuous spectrum into seven parts and names them, so we believe there are seven colors; what about 70 parts? What if there is no concept of "color" in our language at all, but rather the concept of "flavor" is divided into two things that we don't know what it is? Unthinkable. In everyday life, we are basically in a state of non-reflection about these questions, and mathematics can just reverse the "we know the world by rules" thing - establish rules between various things to experiment and play way to try those that "could have been otherwise".

Remember the crumbling Frank Kalman? He is such a math madman. We ordinary people only know that there are boring and abnormal arcane problems such as "fill in the numbers according to the rules", and only know that according to a rule, a number sequence can be formed. But the madman found that any number - no matter how messy - has rules - no matter how complicated, if you are willing to find it, in other words, as long as you are willing to construct a rule for such a mess of numbers, they can be called one sequence. What's even crazier is that for the written numbers, there are not only one, but innumerable, rules that can be constructed; under each different rule, the expansion behind the sequence is also different. The lunatic is not only obsessed with constructing rules for various arbitrary numbers, but also trying to demonstrate why people tend to prefer a certain rule: for example, when we see 1234, we will think that it is followed by 5678, not 19, 45, 67, 98... Although the latter The reader can also find out the laws; with the language analogy, it is as if he wants to find out why we have logical categories such as time and space causality, and not some other.

So he broke down.

Selden didn't collapse, but he suffered from deep fear and guilt.

The source of this fear and guilt is not explained in the story. But the novel hints that the death of his friend and colleague—who is also the nominal father of his illegitimate daughter—seems to be one of the sources. In fact, the death has nothing to do with Selden, but the effect of the death is that he has a better chance of getting close to his lover and illegitimate daughter and avoids the big trouble in the middle. In any case, he was the unexpected beneficiary of this. So he feels guilty and more afraid - we can add reasoning and imagination to the space left in the novel: he is a person who has experienced too many bizarre deaths, and each death has benefited him, which makes him have to make connections in the middle (Construction rules!) as if the death of others was the influence of his subjective will, at least for his benefit. Isn't that what is called serial murder? One coincidence after another just enabled him to keep shifting the murder committed by his daughter, establishing a sequence, and even weaving it into another set of perfectly ordered high-IQ crimes, even the result-the driver's last coincidence- is so perfect. Selden never killed anyone, he just added a little decoration to each accident.

Just as people don't really believe in magic, but rather believe in ingenuity, so readers of mystery novels don't want to believe that everything is a coincidence without technical content, and would rather believe that there is some kind of highly sophisticated design. But for Selden's horrific fate, and for this so-called "speculation" novel, it's the exact opposite: instead of a pre-designed conspiracy waiting to be uncovered, one coincidence after another is chased , connect them in series with the post-hair construction. In fact, isn't this also a self-reference to the speculative fiction writing process?

There are many characters and allusions involved in the novel, but it is still basically a postmodern collage technique, rather than Eco's extensive and profound book-like writing that breaks the truth and fiction. But in my opinion, the movie does not use so many mathematical "decorations" and talks about Wittgenstein at the beginning. This "Wittgensteinization" really grasps the core of the novel's "anti-reasoning".

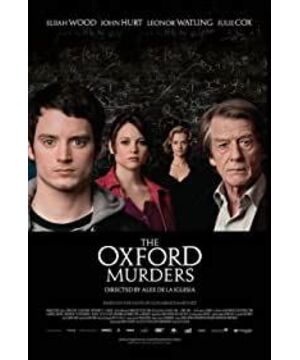

View more about The Oxford Murders reviews