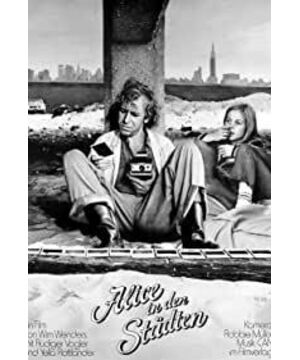

Until I finished watching "Alice in the City", I recalled that winged but sentimental old angel again. The film begins a lyrical journey in the slow motion of the camera, and the road sign that reads "B67 ST" in the opening title leads us down an unpredictable path. But this isn't an adventurous American western, even though it was made on the go. It's not that there is no adventurous spirit in Wenders' films, it's just that that spirit of adventure is squeezed bit by bit by confusion and confusion in the bleak journey.

As the first installment of Wenders' "Road Trilogy", "Alice in the City" did not disappoint me, all I found was some kind of outlandish surprise. This slightly cool-toned romantic story happened to a German journalist named Philip Winter. Winter made an appointment with a publisher to write about American flair, but his four-week trip to the U.S. brought him nothing but a pile of photos that could be found everywhere. Because he lost the ability to write and was blocked by the real world.

Winter's thinking and questioning about life may have begun in the process of driving, which is very similar to the protagonist in Abbas' "The Taste of Cherry". As Winter says, talking to oneself is actually more like listening than talking. And this is by no means Ah Q's method of spiritual victory, at least he can clearly realize that he has been lost in American-style culture. The same motels, impersonal TV shows... The utopian "American Dream" has long been swallowed by the wave of commercialization. When the idealized world came to nothing, what Winter faced was a life of isolation. As the film tells us, when a person loses his sense of self-identity, he also loses contact with the world. And Winter can only self-exile on a journey without a terminal. Winter's self-talk contains the dual meanings of "talking" and "listening". What he talks about is the emptiness of his soul, and what he listens to is the echo of his heart. Only when a person hears his inner voice can he not get lost in the rapid changes of the times.

But Winter's confusion can only serve as a prelude to the film, and the story really begins when he meets Alice. It gave me the feeling that Winter traveled so much just to wait for Alice to come. Wenders cuts into the film from a child's point of view (although the main narrative of the film is always Winter), which brings us back to the most primitive state to re-examine the transformation of the city. If we want to explore the relationship between the protagonist and the camera in this film, we can explain that we are looking into the world of Philip Winter through the eyes of Alice. Winter once told Alice the story of a knight, and that story happened to a little boy. This is not some kind of coincidence, more like a deliberate arrangement by the director. Aren't we more like a naive child lost in the process of urbanization?

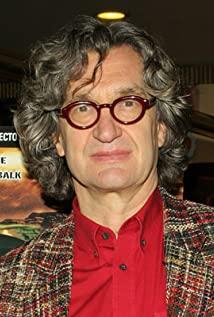

The protagonist of the film, Winter, likes to take pictures with Polaroids, which makes us think of Wenders, who also loves photography. Wenders' films are full of the desire to talk, but is the real listener we, or is it always just himself? Winter's madness reminds me of Vertov's documentary called "The Man with the Camera." But Winter and "the man with the camera" are two completely different types, the latter tending to take pictures that reflect the realities of Soviet society, and he is like a passionate speaker; the former is more like a taciturn mind In the filming, he recorded some sentiments in his life. Winter faces not only social reality but also his inner world, and his behavior is "modernist".

Using this film as a starting point, Wenders moved toward an experiment in "road movies." And "Alice in the City" is destined to be a window into the films after Wenders. Wenders' films tend to be "wandering", which precisely shows the sharp contradiction between the individual and the city in the post-industrial society. It is precisely because the contradiction between the individual and the city is escalating that individuals are more inclined to flee the city. Truffaut, the go-getter of the "New Wave" film, said, "I have always tended to escape from life, and the film is my refuge." And Wenders-style wandering is a process of "refuge".

Wenders consciously inserts a lot of boring TV footage into the film, which bores Winter so much that he destroys a TV himself. The director of "Forrest Gump" has also done something similar, but the TV pictures inserted in "Forrest Gump" are more of a realization of the characteristics of that era and a reflection of historical events. But the TV pictures inserted in "Alice in the City" only hinted that Wenders was tired of urban life. There's a scene in the movie where Winter says to Alice that he can blow out the lights in the building opposite? He really "did it". The lights in the building opposite went out as he expected. The reason is very simple. It is nothing more than that Winter has grasped the time to turn off the lights in the opposite building, because Winter is already familiar with the city. And what does this tell us? When you are highly aware of a thing, all you get is boredom with that thing.

In addition, in this film, there are various means of transportation such as planes, cars, trains, ships, etc., and Wenders wants to tell us only one thing, what really matters is not the way of travel, but What kind of heart do we carry when we travel? After all, it's just a way, or a vulgar form, and all we really care about is the distance.

Wenders' camera has been rubbing violently with the ground, as if talking to the road. There are sharp brakes hidden in his shots, but he is always hesitant, as if thinking about whether to stop? The flowing, moving shots made me fall in love with Wenders' cinematic language, and he broke with montage with a pioneering courage. There are three main reasons why I like mobile photography: first, it allows me to see the passage of time and touch the never-ending life; second, it allows me to witness a wandering heart, a disturbed soul I found resonance; third, the movement of the camera represents the unpredictable future, which satisfies my curiosity and informs me that there are countless possibilities ahead.

It is worth noting that "Alice in the City" was written by Wenders in 1974. At that time, Wenders had not accepted Coppola's invitation to go to the United States to make a film, but his "American complex" was in this film. It has already begun to emerge. It was not until ten years later that Wenders ushered in the "peak of Americanization" with a "Paris, Texas". As a German film director, why did Wenders make films that are "Americanized"? Confusing. Maybe it's because "America" gave birth to the "Beat Generation," where Jack Kerouac's soul is buried. And this is precisely the soil of the "road movie". Wenders' films implicitly have an ambiguity with America, just as Polish film master Kieslowski touches France in his films. In addition to the "first country" (that is, his motherland), there is always a "second country" in the eyes of the artist, and this "second country" is more of a symbolic existence. It's just the artist's love and yearning for "elsewhere" or "new world", nothing more. America will always be a dream that Wenders will never wake up from.

In "Alice in the City", Wenders also used a lot of fading techniques, and the camera slowly dimmed, as if to imply the end of the day, but where will the horizon of tomorrow appear? Every fade is a sunset, a questioning of us, forcing us to remember what we did that day.

Let's turn our attention back to the final scene of the movie. Winter was going back to Germany to finish the book, and he asked Alice, what are you going to do? Alice didn't answer until the end of the movie. It's another movie without an answer, because the answer itself is terrifying, and the answer implies an endless sense of nothingness. And isn't that the answer we want? Only confusion can explain confusion. The director's intentions are self-evident. The train carrying Winter and Alice slowly departed, and the camera began to move slowly in the mournful and mournful soundtrack that repeatedly sounded, all of which seemed to be a bird's-eye view through the glass window on an airplane. It reminds me of the plane that slowly disappears at the beginning of the movie. The end of the film connects with the beginning of the film, constituting an eternal life experience.

And we are like a group of dolls, projecting loneliness and confusion on the white curtain in the bright lights of the city.

View more about Alice in the Cities reviews