Antar's films are not for storytelling, not for enjoyment, but for his own mission. As he himself said: an artist should undertake a mission similar to God, and artistic creation is not self-expression or self-realization, but to create another reality and a spiritual existence through self-sacrifice. Likewise, he sees film as "the church of the twentieth century." From this understanding, his films are indeed worthy of one of the trinities in film history!

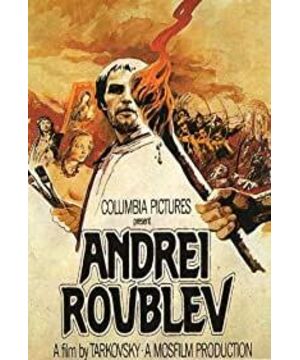

In fact, he still told a complete story: the journey of a painter named Andrei Rublev before he completed the most famous fresco. Through this experience of his (Lublev), he expresses the director's own views on the nature and function of art, and the exploration of the artist's spiritual world.

What's special is that the director didn't make the movie succumb to the narrative... but used the picture, sound, and video as a kind of "brick" to build a complete palace. When thousands of bricks were piled together in different orders, and we retreated to the hillside to look at it, we were surprised to find out: Oh! ...that's a palace! And the narrative - the story of "Andrei Rublev" is just the name of the palace.

Anta's flowing shots, the poetic film language needs no more talk. Those techniques, if not for expressing deep spiritual content, would look like a frown. There needs to be a smooth overall sense, a delicate understanding of architecture, in order to control such a lens language. Just like a horse, a tree, a puddle of water, a pile of ashes... It naturally touches people, but they don't know why they appear here.

PS: Reminds me of "Brecht"'s performance theory: the alienation effect. Actors are required not to bring the audience into the drama completely, and to generate their own thinking while watching the drama. The same goes for "Meyerhold," which isn't just content with drama telling stories...

View more about Andrei Rublev reviews