- Sigmund Freud

Antonioni's film is like a dream. The sensual and present reality often overrides the rational drive, while deep philosophical speculation is hidden at the bottom. Like many other great directors of that era, watching Angong's films was one that had to endure loneliness, not only because of his age and themes he presented, but also because of the aesthetic distance required by art appreciation. It is also because in the master's unique and uninhibited cultural concept, the attention to morbidity and alienation (including the spirit of the characters and the spirit of society), and the thorough understanding of the indifferent sense of alienation between society and life, are no longer able to be revealed to the audience in a few words from his works. loneliness. No one is more suitable to restore a dream than him, because he is skeptical about the art form of film itself, because he desperately binds his thoughts to a simple lens to show.

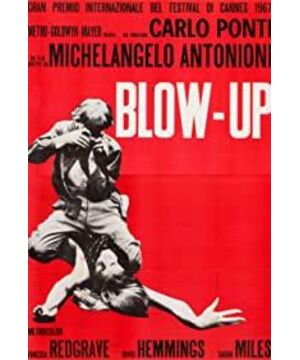

The story of "Zoom" itself is very dramatic. Such a plot setting, which is both true and illusory, involves elements of murder, desire, pursuit and exposure, and a little outline of film language is enough to watch and attract. force. The 1981 film "The Fierce Line" starring John Travolta is a successful work born out of this concept model. However, An Gong's obsessive-compulsive disorder has not allowed him to use normal film language to tell a story that follows popular culture. The film's indifference to the plot, as well as the protagonist's consistent sense of emptiness and alienation, reflects the indifference of the whole world, which confuses the real and the false, in the descriptive shots of the director's zooming and pushing. The basic actions of the protagonist Thomas are a typical set of sensory and cognitive behaviors, from the initial unconscious whim, to conscious induction when discovering strangeness, conscious interpretation when seeking the truth, and finally to the unknown and unknowable illusory ending. This is a story that has lost its climax and rhythm, and even calling it a story is a bit unformed. The photos that should have been key props in the traditional narrative mode, and the witnesses, murderers, and victims that should have been key accounts, all lost their weight in the slow-moving panoramic frame. An Gong's films have a height that makes others envious. No matter what kind of story he tells, he can easily focus the center of light and shadow on a spiritual realm. The cultural appeal behind the action and character actually tore the illusion. , jumped from a subordinate position to become the real protagonist of the film.

This film is at a conspicuous turning point in the middle and late stages of An Gong's film and television career. In the middle and late period, Antonioni gradually withdrew his enthusiasm for neorealism and put more thought into postmodernism. Although the film's previous "emotional trilogy" also uses his usual slow speed concept, it shows the worldly people who are involved in certain events and get into trouble. But in these films, one can clearly read the images of the hero and heroine and their incisively dismantled inner worlds. The disdain of "Zoom" in these aspects makes the film more inclined to theoretical spiritual reading in a situation that is detached from humanitarianism. In Antonioni's delicate relationship with society and with the film itself, "Zoom" goes further than his earlier films.

The camera is an extension of human vision in the film, and the photos of the crime scene taken are further expanded through layers of magnification. Like film technology, it reflects the pursuit of technology and supernatural abilities by the entire human beings. The result of this pursuit is emptiness and vain. Thomas found the corpse in the photo and went to the park alone; after finding the corpse, he turned back alone, and could not find anyone who believed in him; the photo as evidence disappeared, and the body as a direct participant also disappeared... A series of bizarre events make the characters Faith in reality collapsed in an instant. I've always admired An Gong for his ability to pull the camera's eye to a higher level than the mundane in his rigid telegraphed dialogue and highly restrained performances. Long periods of silence and drowsy, dazed action, even stingy to add superfluous artificial sound effects. However, the significance of thinking aroused by such works is unprecedented. He focuses the audience's thinking more on the consequences of events rather than the causes, which is contrary to the classic drama rhythm and the spirit of tracing the origin of human instinct. In the long shots, the raucous and frenetic students, the chaotic and decadent drug addicts, and the crazy hippie rock concerts randomly sketched the vacuous emptiness of that era and the morbid structure of social bloodshed. Such a life has long been divorced from the truth.

There is a scene in the film where two teenage models come to Thomas' studio, and in a playful chase, the cynical photographer is enjoying themselves (the reason should be to make the models in better condition and take better pictures) ). The insertion of this bridge segment is very abrupt, like a tumor on the trunk. But such an uninhibited and uninhibited behavior, and its unscrupulous self-government for light and shadow art, is very similar to Antonioni living in his own world.

This is a purely sensory film, or a purely visual film. The discussion of the image of the eye has always fascinated me, wearing too much religious and mythological veil, and bringing out too many legendary and romantic stories, such as Narcissus, such as Oedipus, such as Faust . An Gong toyed with his diligent diagnosis and lazy treatment, giving out the mysteries of life in this world, pointing out such empty and alienating illusions, without proposing solutions. Cinema may be such an unresolved art. When Thomas picked up the invisible tennis ball at the end of the film and acted out this silent farce, we still can't tell whether he was surrendered or helpless. Life has nothing to do with the truth, and movies are even less qualified.

Postscript: The main purpose of writing this film is to understand more about Antonioni. The other day in Sanlitun chatting with cannabis, he said that this is already the most popular of An Gong's films. Today, when we look back at Antonioni (including Bergman, Fellini and Truffaut), it is no longer possible to appreciate the milestones in the history of cinema that he left in that era with empathy. He is epoch-making and deified. Even the diversified expression paths he has opened up for film art do not need to rely on anyone's text commentary to win the respect of the twilight. The deceased is gone, and the long river of the movie is still flowing, but the innocence and purity have faded away from the past.

View more about Blow-Up reviews