Many critics said that the film had some "humanitarian flooding" meaning. It is easy to find evidence for this argument in the details: for example, in the episode where a few nurses were screaming for the little one by the well in the middle of the night, are other patients not sleeping? It's a bit like "political correctness" in some countries. Similar details are certainly flawed, but the reason for being rated as "flooding of humanitarianism" is probably not on the surface. Perhaps the theme of this work is somewhat distant from Chinese culture.

Let's start with the most superficial sensory stimuli. What caught my attention the most was the close-up of the death of Roksuke (the lacquer painter whose wife and daughter were taken away by another man twice). This is the first time I've seen death as a process. The so-called process is different from the moment when the bullet falls to the ground or the patient suddenly tilts his face to one side on the bed. There is only Rokusuke in the shot, and there are no other people or even objects around him: his mouth is open, his whole body, or the last bit of strength left in his entire life, is gathered, as if to make a broken, hoarse sound. It was unclear whether he was struggling, waking up, or trying to talk. All film language focuses on the disappearance of life, and this disappearance is so long that people really realize that death is a process, not a moment whose length can be ignored. This length may carry a meaning different from the moment, and it is not just a simple announcement of the end of life. When instructing Baoben to take care of the dying six assistants, the red beard said to Baoben: "The death of a person is a solemn thing, you have to look at it carefully!"

However, this pain, this struggle, this attachment born from the desire to live , How can we talk about solemnity? It seems that the solemnity of death, in the hearts of many people, only the dying can have peace of mind. For example, the great monk who passed away peacefully, or the samurai who calmly cut his abdomen.

The plot continues, and the mouth of the daughter of Liusuke, who has been looking for her father, tells what happened to the deceased before his death. He used to have passionate love, and because of this, the series of blows that his wife and daughter were taken away gave him even more pain. ─Koishikawa sanatorium. Such a person, when saying goodbye to life, does not express resentment. Perhaps in the lonely journey of life, he realized with difficulty, complaining that he could not save himself; only love can save those who are caught in the rupture of life. But no one loves him, he can only love himself and try his best to love the rest of the journey. Yet self-love is not only difficult to achieve, it always seems to be insufficient. In the end, it's hard to calm down, and it should be considered solemn for a person who has lived such a life to have no complaints at the end of his life.

When it comes to love and redemption, this theme seems very close to Christianity. People need to be saved, and love is what saves. This is probably Christian thinking. The benevolence in Chinese does not seem to save others, but only a norm for oneself. A world full of benevolence is harmonious, perfect, flawless, without cracks, and no one is trapped in it, so what is there to say about salvation. However, this utopia may only exist in the past in the scriptures, the present in the mouth of Ning Chen, and the future in the poetry of scholars. And it seems that for every real person, for everyone's real time, there are cracks in life: when one is alone, the past about those cracks can easily come out from the bottom of my heart; In time, it will come in waves like a tide. When faced with this flood of self-experience, how should a person face it, the death of Liusuke is an answer.

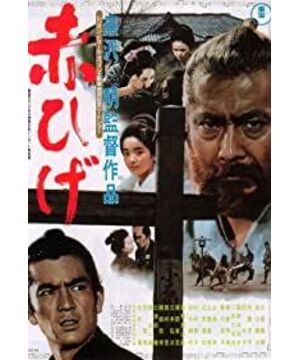

View more about Red Beard reviews