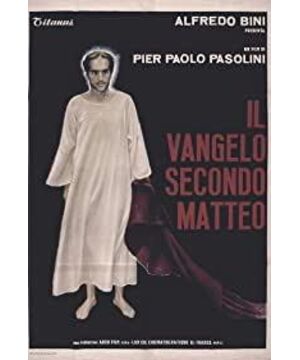

- Director: Pasolini

Text: Roger Albert Translation: Joshua

Pierre Paul Pasolini Once in Assisi, the hometown of St. Francis, in 1962 When he went there to attend a seminar at a San Franciscan monastery. Although Pasolini is known as an atheist, Marxist and homosexual, he accepted an invitation from Pope John XXIII for a new round of dialogue with non-Catholic artists.

The streets were crowded with the Pope's arrival, and Pasolini had to pass the time in his hotel room. He found a Gospel and "read it all in one go." The idea for a film based on one of the Gospels, he wrote, "made me leave all other work ideas behind." The result was this film, mostly set in the barren and desolate Basili of Italy. "The Gospel of Matthew" (1964) photographed in the Kata region and its capital, Matera. (Forty years later, Mel Gibson will be filming "The Passion of the Christ" in the same location.)

Pasolini's film is one of the most impressive religious films I've ever seen, Maybe it's because it was shot by a director who doesn't believe in God: he doesn't preach, he doesn't praise, he doesn't stress, or sentimentalize, romanticize the story, but just tries to document it.

I learned that anecdote about the hotel room myself, and much of the rest of the information below comes from Bass David Schwartz's "Pasolini Requiem"—a piece about the work involving profanity and A sacred, highly valuable work by a down-and-out artist who was eventually murdered on the outskirts of the city.

Although Pasolini directed about 25 films in his lifetime (most notably "Parasite," "The Big Bird and the Little Bird," "120 Days of Sodom," "Ten Days," "Mama Roma," and "Theorem" ”), and wrote the screenplays for Fellini’s “Nights of Cabiria” and “La Dolce Vita”, but before he became a director he considered himself a poet, and his films consisted of images, Impressions and words that sometimes function as a language rather than a dialogue.

This is naturally the case with "The Gospel of Matthew," which is like a low-budget documentary that chronicles the life of Christ from the birth of Christ. The film is shot in the spirit of Italian neorealism, which advocates that everyday people, not professional actors, can best embody the characters—not all the characters, but the one they were born to play .

Pasolini's version of Christ is Eric Iraoqui, a Spanish economics student who came to him to talk about his work, Iraoqui never acted, but Schwartz quotes Pasolini "Even before we started our conversation, I said, 'Excuse me, can you be in one of my films'?" Schwartz described Iraoki: "…a man made by a Basque father and The son of a Jewish mother… thin, stooped, with thick eyebrows, nothing like the muscular Christ of Michelangelo.”

Pasolini cast local farmers, shopkeepers, factory workers, truck drivers in other roles , the Virgin Mary at the crucifixion was played by his own mother.

Whether these actors can handle the dialogue lines without discussing it. Pasolini decided against the script, filming page by page from the Gospels, with only the necessary compression to keep the film at an acceptable length. Every word in the dialogue is straight from the Gospels, and many of them are from long-range footage, so we don't see the lip movement.

Jesus is often seen speaking, and his demeanor and appearance are quite different from traditional portrayals. Like most Jewish men of the day, he had short hair—not downright as in the Holy Cards, and he wore a black hooded robe so that his face was often in shadow middle. He wasn't shaved but he didn't have a beard either.

His personal demeanor was sometimes milder, as in the Sermon on the Mount, but more often he spoke with a righteous anger, like that of a coalition organizer or anti-war. His debating style, faithful to the Gospel of Matthew, is to answer one question, one parable, or domineering sarcasm to another. His sermon was clearly a vehement rebuke of his society: its materialism, its way of value judgments that put the rich and powerful above the poor and the weak. Listening to this Jesus, no one would confuse him with advocates of prosperity, even though many of his followers thought he would reward them with abundance.

This black-and-white film is told in a downright pristine way. Think about starting that scene. We see a close-up of Mary, we see a close-up of Joseph. Long shot of Maria, she's pregnant. We see Joseph musing about this, and we see him come out of the house and fall asleep against a large rock. He is then awakened by an angel (who looks like an ordinary peasant girl) who tells him that Mary will give birth to the Son of God. Later the angels foretold them to flee to Egypt before Herod ordered the slaughter of the firstborn.

The massacre of the babies is a brief scene, the more horrific because Pasolini does not use closeup details of violence. Here, and later, he used the soul song "Sometimes I'm Like a Motherless Child" on the synth track - I think it came from singer Odette, although some sources cite Marian Anderson. The pilgrimage of the three saints of the East was photographed as if it could have happened, riding on horses (not camels), followed by a group of cheering children.

In fact, curious children seem to be drawn to Jesus. In the scene of the debate with the elders in the temple, the children sat in a row at his feet, and when they thought he had said something wonderful, they turned and giggled to the elders in a showy way.

The miracle of walking bread and fish, and walking on the sea are handled in a low-key manner. Christ made his disciples sail, "I will follow you." No triumphant music, no arm waving and no cries of distrust, no sensuous camera angles—just a lonely silhouette walking on water, a long shot.

The trial of Jesus in this film, like Gibson's "Passion of the Christ," has a lot of rebukes against the high priests of Judaism, as is the Gospel of Matthew itself. But those who find anti-Semitic tendencies in Gibson's portrayal of them are likely to appreciate Pasolini's determination to film those debates with a long lens, and the monks he shows are not angry and vicious, but erudite, dull, very knowledgeable Take heresy seriously. Pasolini's monks concluded, "He must die and hand him over to Pontius Pilate." Pilate called Jesus an "innocent man." Then we hear the infamous line from the Gospel of Matthew, "May his blood be sprinkled on our children." Gibson later cut the line from his subtitles (but not from the Aramaic dialogue).

The crucifixion scene has absolutely none of the violence and blood in Gibson's version. It's almost an understatement, and we notice that most of the way to Cavalli, the cross is carried by Simon, and Jesus just walks behind it with a crown of thorns on his head, but only a few drops of blood. But this version isn't as muted and dramatized as Hollywood's biblical epics, with a gritty realism that looks like a natural depiction of a brutal death process.

Andrew Greeley, in his essay on Gibson's films, corrects the notion that Catholic school graduates (like me) were told that Jesus died to atone for man's original sin. Greeley said he died because he felt our pain and because he loved us. It was a Jesus that was closer to Pasolini's version, but Pasolini also insisted that Jesus did not love those whose kingdom was on earth; his Christ was on the left, not on the right, and would bring together many contemporary Christians and those who Rabbi and Pharisees are regarded as a raccoon dog.

"The Gospel of Matthew" won the Grand Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival (the Golden Lion went to Antonioni's fiercely secular "Red Desert"). Right-wing Catholic groups were wary of it, but the film received its first accolade from the International Catholic Film Institute (OCIC), which also screened it at Notre Dame; the French left was as outraged as the Italian right, Sa Terrence met with Pasolini and told him cryptically, "Stalin has resurrected Ivan the Terrible, and Christ has not been resurrected by the Marxists." Watched it weeks after seeing Gibson's The Passion This film will make it clear that there is no one version of Christ's story. It's like a template into which we can inject ideas, and we'll see it as dictated by our life experiences. Gibson sees the suffering of Jesus as an overriding fact of his life, so his films do not contain much of the teachings of Christ. Pasolini believes that teaching is the core story. Suppose an audience member who had no prior knowledge of Christ ran over to Gibson's Passion and wondered what all the frenzy was about, Pasolini's film would convince him that Jesus was a radical , his teachings, if taken seriously, would contradict the values of most societies throughout human history.

View more about The Gospel According to St. Matthew reviews