It's no surprise to see the ending.

The film is filled with the inconspicuous little things that happen every day in our daily lives. The confrontation between the rich and the poor, the gap between culture and illiteracy, is so common and common.

My first feeling while watching it was calm and then depression. The director uses restrained shots and a watertight script to calm the audience's emotions. The film does not use any special techniques and structures. Everything feels as ordinary as this cold winter.

The two heroines are really similar, with such stern faces, down-looking eyes and extremely thin lips, both are proletarians, but Huppert's role is more extroverted. She has a clear stance, is a bit literate and can read, and has done charity service for the church before. She seems to be experienced, understands the daily life of the middle class, and peeks into their thoughts from their emails. She's casual and dangerous, she's always hated the middle class, and hated Melina, who was pregnant and had the forgiveness of her family. There are traces of her ruthlessness. She will take the initiative to understand the ideological life of the middle class, and she will also encourage Sophie to resist and spurn them. She also sympathizes with the poor who hate the rich as much as she does. And when you look at her frivolous tone and bold eyes, her small figure and out-of-tune dress, you should know that you can't have a deep relationship with her.

Looking at Sophie again, when I didn't know that she was illiterate and tried her best to hide it from others, she was just a silent and industrious person, her always pretty face was indifferent and a little "weird". But once she found out, her tall and thin body hunched up. She lay desperately beside the bed, daring not to ask anyone for help, and so naturally concealed the fact that she was illiterate with lies, and turned up the volume of the TV to escape. The call of the father's phone and the knock on the door of the secretary, this indifferent and dull woman is like a frightened child when she encounters this topic. She uses all clumsy means to maintain her face and dignity. She doesn't understand the life of this middle-class family, what they wear and see, and she can act as a factory machine and work diligently in mechanical labor, but she can't let anyone know her illiteracy and ignorance.

Sophie is absurdly ruthless, and no one knows why an ordinary person like her kills her father and kills her family and former friends without blinking an eye to cover up this dyslexia defect. Her eyes are big, but they are full of confusion and emptiness. She has no expression or standpoint. Even apart from her work, she can only get a little entertainment from that side of the TV like a child. The audience doesn't know where she is from, Has she ever been in love, what her preferences are, and why is she so cautious and indifferent. She has been wearing a blue top with short bangs, monotonous words, quiet and boring to the extreme. Is she really that inferior? Why did she fire a bullet without any hesitation at all?

She is like a lonely beast, vulgar and silent, always staring at something with those beautiful blue eyes, she has no purpose, no stand, or even emotion. This reminds me of a psychotic, sociopathic personality. But she was only part of the disease, lacking affection, lacking depth.

I don't think that what the director wants to express is the element, class, that has been included in all literary works more or less throughout the ages. It's just a necessary background factor to document this fictional story, as unimportant as the heroine's identity. Her motive for killing was so simple, and it would never be so simple in reality. But it's absurd and real, with cut-and-white photos haphazardly pasted on the pages of a surreal novel, simply and head-scratching.

When I saw Sophie shoot the father of that family without hesitation, only one word came to mind, FALSE. Mozart's opera is playing downstairs. The two guns are like prank toys for children. The expressions on the faces of the two protagonists are ridiculously flat, like a play with out-of-tune colors. Everything is the trivial things that can be seen in reality, those people, those relationships, politics. But the most irreversible tragedy happened so unmotivated and savagely.

The reality is originally so absurd, except for those rational, civilized, and social psychological analysis, the final direction will be beyond unexpected absurdity, and it is really contained in the word "destiny", and the puppets are all predetermined. every action. The director did not deliberately express the fiction of this story, nor did he add much depiction and refinement to present it to the audience in its most real appearance. The consequences of all those actions are like a "transparent glass house", with unavoidable sincerity. naked. Sophie stared blankly at the tragedy she caused at the end. Those who came to hear the news were like a pale and lifeless god. You never know what she was thinking and what this illiterate illiterate thinks. Your words and deeds to her.

To analyze whether the family that Sophie served was good to her, the people's life in the background, and even the director's own life experience seems to have nothing to do with this film at all. It does what art is: useless. All that was left was the shudder and gloom that the false atmosphere of the two heroines gave me when they shot, and the still beautiful and empty face of the heroine hidden in the shadows.

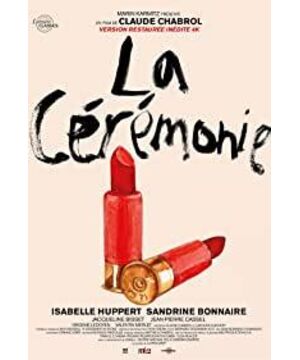

View more about La Cérémonie reviews