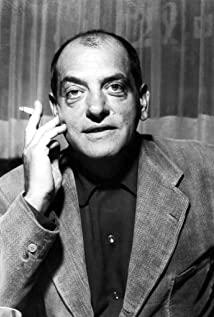

This strategy was further extended by two French films, which coincided with the arrival of the sound film and the end of the first wave of avant-garde cinema before the rise of Hitler. They are "The Golden Age" (L'Age d'or; 1930) and "Blood of the Poets". Almost the same length as standard films, these films (privately sponsored by art patron Vicomte de Noailles and successively as a birthday present to his wife) combine Cocteau's lucid classicism and surrealism. the creation of the Baroque mythology. Both films satirize the visual sense, either in narration or in the form of intertitles (both films were made during the rush hour of sound film, and they used spoken and written texts). Cocteau's piercing sarcasm of his poet's obsession with fame and death (those who smash statues beware of becoming statues) corresponds to the opening line of "The Golden Age" with a scorpion "Lecture" and subtitles attacking ancient and modern Rome. Buñuel links the decline of the classical age with his main (attack) target, Christianity (Christ and the apostles appear to have just left a Saddian boozing feast at a manor in the film). The film itself celebrates "crazy love". A text by surrealists signed by Aragon, Breton, Dalí, Paul Éluard, Benjamin Péret , Tristan Tzara et al., released in the first shot: The Golden Age, "Plausible Incorruptibility", revealing "the bankruptcy of our emotions linked to the problems of capitalism". This manifesto is reminiscent of Viggo's admiration for "An Andalusian Dog": "Barbaric Poetry" (also in 1930), as a "socially conscious film". "The howl of an Andalusian dog," wrote Viggo, "who will die after that?" (Jeffrey Norville-Smith, "World Cinema History")

View more about L'Age d'Or reviews