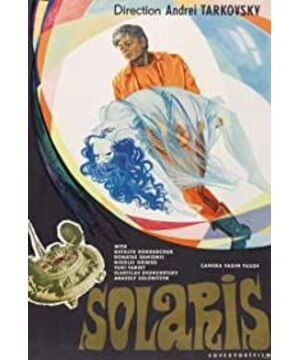

Tarkovsky's "Flying to Space", also known as "Solaris (Star)", is adapted from the Polish science fiction novelist Lem's novel of the same name: "Solaris Star". Ta's inherited a philosophical theme in Lyme's novels, the problem of epistemology. Chris's group of scientists called it "consciousness", but in fact here, like Kant and Husserl, they are all concerned with epistemological issues. But, specifically, the Solaris Sea, from its philosophical meaning, is exactly the "thing-in-itself" in the sense of Kant. Solaris - in a metaphorical sense - is the study of the thing-in-itself - then, it is doomed to be a futile study. Because the thing-in-itself is against rationality, it is beyond language and cannot be known. But whether it is Kant, Tarkovsky or Lem, in fact, there is no tendency to slip into agnosticism (our agnostic judgment of Kant's thought is actually a misunderstanding [1]): what the three are opposed to is Enlightenment Deep-rooted anthropocentrism brought about by reason. They are reminding us of another possibility of existence—or, rather, the obscure enclaves of existence that cannot be illuminated by words. Tarkovsky kept a quote from Lyme in the film: "Are we really trying to conquer the universe? No. We just want to push the edge of the earth to the end of the universe." Lyme and Taco In different ways, Fsky tries to reveal the darkness of existence to us .

[1] See the Kant part of [Russian] Guregia's New Treatise on German Classical Philosophy.

The exploration of epistemology, however, is by no means the reason why Tarkovsky's films have their sensual brilliance. The distance between the philosophical subject and the aesthetic effect of the film cannot be overemphasized. The former resorts to language, the latter to vision. Ta's "Flying to Space" is 166 minutes long, but I rarely get bored during the viewing process. Why? There is, to me, a faint unease and tension that pervades the film throughout. We need to describe it more clearly so that we don't misunderstand the meaning of "tension" here. This kind of tension is the panic of being overwhelmed when faced with a huge and silent thing, and it is also accompanied by the sense of silence caused by being plunged into darkness due to a sudden power failure at a brilliant banquet. It is extremely light and far away. It 's not as immediate as horror , but it's the only thing that lasts -- this faint feeling like a murmur in the middle of the night has been pulling our nerves when watching movies. It lurks in the fringe field of the visual picture, adding a new look to our viewing. This situation became more apparent after Chris entered the space station.

Specifically, Tarkovsky completely disrupts the shot logic of traditional film narrative: one shot follows the next, with the help of the second shot we can understand the first shot. Tashi rejected this set, and he asked us, extremely calmly, to stop a little longer on the first unintelligible shot. In "Flying to Space", he also cancels the overlapping relationship between the point of view of the camera and the point of view of the characters. This is evident in a series of empty shots at the beginning of the film. Teacher Dai Jinhua has made a key analysis on this. We seem to be looking at Chris through someone's point of view, but every subsequent shot of Ta's is breaking our expectations for a "viewer". Not only is there no "people" watching Chris, but Chris is not watching anything: he just appears from the left side of the frame, moves to the right, and disappears. What followed was Ta's iconic heavy rain: it came suddenly, but the camera was extremely quiet, almost a kind of stare, aimed at the fruit plate and tea cup on the table, at the expressionless Chris. In this heavy rain, all eyes and actions are suspended, there is no certainty, and there is no causal relationship. The series of continuous empty shots at the beginning of the film has already announced the establishment of another sense of science fiction aesthetics: science fiction as an opposition to realist narrative methods. This means that, since Fielding, canonical realism has established its narrative norm precisely through the organicity of the plot—that is, “things happen for a reason.” The Tarkovsky-style narrative cancels the organic nature of this plot. But this is not to say that he has returned to the loose structure of the hobo novel. How to make the film still have a narrative function and become an organic whole? In my opinion, it's through the aforementioned tension that never dissipates from beginning to end.

Through the dehumanization of lens language, Tarkovsky cancels causality in the traditional sense, and in fact a meaning center. As Yeats said: "Everything is scattered, and the center can no longer be kept". The mysterious "visitor" in the film is not only the other completely different from the cognitive subject, but also from the subject itself. The film says that visitors are made of "neutrinos," while our bodies are made of atoms. Whether or not there is a scientific basis behind this is immaterial. Tashi just wanted to tell us that these visitors were definitely of the opposite sex. These visitors prompt us to ask the scientists over and over again: What are you "are" ? Who are you "are" ? However, this heterosexuality was broken by the appearance of Harry. As the film progresses, Harriet begins to act a little jerky, and gradually becomes independent and outspoken: she no longer has to ask herself to see Chris all the time. And when she finally realizes that she's actually some kind of handicap for Chris, she drank the liquid oxygen to try and end herself. What Tarkovsky wanted to explore through Harry was undoubtedly the theme of "love" that no ordinary philosophy could distinguish. After having strong feelings, the "Harry" who materialized from Chris's consciousness realized that she was not Chris's real deceased wife - but this did not affect the two of them falling in love. Chris's wife, Harley, died of a drug injection, so the "Harley" embodied by Chris's memory in the space station had a piece of clothing torn off on his shoulder, revealing the eye of a needle. This was the Harry he longed for and feared in his heart. Chris helped the first Harley cut her clothes, put her into a down jacket, and sent her into space; when the second Harley appeared, she began to cut her own clothes - Tarkovsky hints us with this detail , "Harley", who is constantly resurrected, will retain the memory of the previous generation. It's just that for the second Harry, she still doesn't understand what is going on with this dress, she just thinks that the clothes are cut with scissors. Chris must have realized this, too, and was deeply upset by how badly she looked behind the door.

I thought that Tarkovsky's portrayal of Chris and Harry could not be understood in a traditional sci-fi context: reducing it to something like "When the object of love is 'alienated' into inhumanity, Is love still possible?" or other "Ship of Theseus" questions. These questions are not in line with Tashi's intentions. He has no intention of extolling the so-called "love" that transcends life and death - as Soderbergh's other "Solaris" shows - behind Tarkovsky's tense film aesthetics, always There is a scrutiny of the strangeness of existence. It is this very dark thing that makes Chris and us feel a constant unease. Tarkovsky rejects Soderbergh's Hollywood hallucinations, as well as the visual spectacle of traditional sci-fi "blockbusters." He seems to be quite alert to the "existence of the non-existent" that Levinas likes to talk about (I don't mean there is any causal relationship between the two, there is only a parallel relationship between the two). The subject is always powerless in "Flying to Space", and always needs to be responsible to others, but the ethical relationship between people cannot be brought into the same cognitive track - when Chris first arrived at the space station, Communication between the three was extremely chaotic and ineffective. Because there is something overflowing with the power of language at this time, communication becomes possible again only when Harry actually shows up. But for everyone outside the space station, this is another impossible existence. For Levinas, being is, first of all, an "il ya," that is, an unnamed being, which, like expressions like "it's hot" or "it's raining," has not yet broken free from it, has not yet become a being. Lie personally experienced World War II, the greatest catastrophe in human history. He was imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp and nearly died. No other family members survived. This experience greatly influenced his philosophical system. Beneath this philosophical system of Lie, there is actually a kind of extreme horror, which is so thorough that it does not appeal to emotion, but to our more fundamental sense of existence— — This is essentially the kind of “nervousness” I mentioned in the first paragraph of this article. It does not materialize into any emotion that can be captured and described, but it is deeply hidden in the marginal realm of our consciousness and feeling.Dai Jinhua believes that "Fly to Space" is actually a horror film. According to her description:

This horror comes from the depths of our hearts, from our memories, from the most painful abyss of our lives that we cannot face.

I agree that "Fly to Space" is the definition of a horror film, but I don't agree with the conclusion that this horror comes from "memory". The horror of "Flying to Space" is in the sense of ontology and ethics: it is the existence of the other that becomes my question of the autonomy of my own existence. Tarkovsky continually reinforces this through unpersonalized footage. He reinforces this not just by applying the method objectively, but by breaking our presupposed expectations of "someone watching" time and time again. Tarkovsky used the viewpoint shot, but through editing, he canceled the viewpoint attribute of the previous shot, and canceled the source of meaning that should have existed. In addition to this, in fact, he continues to show us another, more transcendent existence. I can't say it's theological or fatalistic, I can only say that the understanding of this sort of thing should have been incorporated into our understanding of "being." Our understanding of "being" should preserve a dark area, rather than wanting to illuminate every inch of it with the light of reason. Here, in a way, Tarkovsky and Levinas are one and the same: while other philosophers and directors are in brightly lit rooms, talking about the power of human cognition, Tarkovsky Both Levinas and Levina chose to stand outside the room filled with endless darkness, staring through the window, but did not say a word. It is in this boundless silence and electric rustling that we are able to come face-to-face with a most profound existence.

View more about Solaris reviews