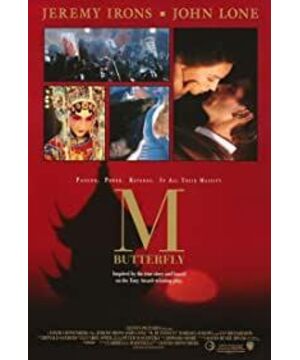

"Jun" and M: An Identity Story

There is an interesting difference between the English title and the Chinese translation of the film. The English title of the film is M.Butterfly and M. is the abbreviation of "Monsieur" (Mr.) in French, and only refers to men. Western audiences familiar with music will think of Puccini's opera "Madame Butterfly" when they see the title. (Madame Butterfly), therefore, the movie has already prompted the audience to disguise as a man at the beginning of the plot, the focus is not on the "discovery" of the real gender of the characters, or the surprise of the final gender reversal, but on how the characters in the film are treated. Misplacement of gender identity [1] . This makes "Mr. Butterfly" a veritable exploration of identity, especially identity. From one perspective, it is a deconstruction of Western narratives from a gender perspective; from another perspective, it is a love tragedy caused by identity conflict.

From "M.Butterfly" to "Mr. Butterfly", the former is like a woman but a real man, suggesting the key turning point of the movie; while the latter is more like a vague and neutral title, which has the taste of being able to distinguish between male and female, but does not Without regret, the parody and intertextual meaning of the original title has been lost. Just because translation is probably the art of regret, even using a more radical means to translate M. Butterfly as "Mr. Butterfly" may be self-defeating, because the Chinese audience's story of Puccini is also the narrative of the film's fuss. The structure is not familiar.

After "Mrs. Butterfly": Inversion and Transcendence of Narrative Structure

The reason why "Mr Butterfly" has the charm of introducing deep thinking lies in its multi-meaning drama. Different from ordinary movies, its drama lies not only in the ups and downs of the storyline, but also in the multiple turns and even reversals of the narrative structure, giving the movie a rich space for interpretation.

Expanding in chronological order, the first narrative structure is the most obvious, but the oriental elements that have been transplanted in the title constantly appear, pointing to the plot of the opera "Madame Butterfly": a simple and promiscuous Orientalist myth written by Westerners. The protagonist of the story is a submissive, beautiful, devoted oriental woman and a ruthless, rambunctious western man who is not worthy of her selfless, noble love, yet she gave her life for him. In the first scene of Song Liling and Rene Gallimard, Song performed a fragment of "Madame Butterfly". This is the first time that the structure of a play within a play appears in the film. The editing method of the shots is not different from that used to present performances. That is, we first give the performer a medium shot, and then cut to the close-up of the audience. We first see Song, who is shining brightly on the stage, and then we see Rene's eager eyes watching Song. This shot clearly contains a dual narrative structure: Rene's gaze plays both a narrative role in the film (reflecting his fascination with Song) and a meta-narrative role, becoming a reflection of the audience's gaze on Song, a refer to. Rene sees, and is also seen by the audience. Interestingly, the gaze of the film audience off-screen turns Rene, who is the subject of desire in the narrative layer, into an object. While the audience outside the narrative layer is staring at Rene, they are also staring at the mirror image of their own desires. (I can talk a little bit about Lacan here, but I am too lazy to read the original text) This tension between the self and the other, or the inner contradiction between the self-image and the image of the other, constitutes the most important part of the figure of Rene. The main inner tension.

As a Westerner, Rene was obviously unable to really perceive the loopholes in the first narrative structure. However, with the deepening of the relationship between Song and Rene, the film first appeared from an Eastern perspective, and the narrative structure of "Madame Butterfly" was subsequently affected. to the challenge. After removing Madame Butterfly's makeup, Song bluntly tells Rene that the story is "beautiful only for Westerners," and goes on to point out the Orientalist character of the "East/West-Female/Male" narrative, in which In the eyes of Westerners, the West is masculine, powerful, and subjective, while the East is always feminine, feminine, mysterious and incomprehensible. It reveals the naked race-gender power behind the seemingly personal theme of "love" Relationship: "Imagine a blond beauty falling in love with a short Japanese businessman. He keeps giving up and she never leaves. You will think she is stupid and crazy." Song's words once again reflect the impact of identity perspective on interpreting narrative layers: Whether a story is moving or not aesthetically pleasing depends not only on the artistic excellence, but also on the identity of the audience.

The story has developed so far, and the audience has glimpsed the loopholes in the first layer of narrative mode. Paradoxically, just when the audience expects the story to break through this structure and develop in the opposite direction, the film forms a second layer of narrative structure.

The second narrative structure runs through the film, starting from the parody of the first narrative structure, and finally dissolving and surpassing the first narrative structure. In the middle of the film, a Chinese cadre came to Song's house angrily and scolded Song as "degenerate garbage", but then took out a small notebook and carefully wrote down the US military information that Song said. Here, the first layer of narrative structure seems to be subverted: Song and Rene's relationship is not Madame Butterfly-style pure love, but lust and Caution-style espionage. It is worth noting that although the national element was added to the original Eastern/Western-female/male narrative in this play, it did not fundamentally reverse the original narrative structure. In this scene, the state replaces the lover as the figure for whom sacrifice is required. As Song said to the cadres: "For the prosperity of the proletarian state, I am willing to bear all the depravity of the bourgeoisie." However, such words cannot win the trust of the cadres, and the words of the cadres reveal Song's embarrassing situation: he is more like a double agent, playing the East to obtain information (and love?) in front of Westerners, while in front of state power They also acted as victims and servants to protect themselves and to retain the right to love that was considered perverse under the patriarchal system. So far, Song's image is vague and ambiguous (we don't know when she became a spy, and it was a trap for Rene from the beginning? Or is it a last resort after Song and Rene were caught cheating by a maid? [2] ) But it is very clear in a higher sense. He is always just an actor, playing different roles in front of different people, just like his monologue at the end of the scene: "I'm trying my best, to become someone else." [3] (When Song said these words, the camera was aimed at the illustration of Anna May Huang in the magazine, an oriental woman who broke into Hollywood under the hegemony of the West, and she formed a delicate intertext with Song.) Whether it is for Rene or for cadres, he They couldn't be truly frank, not because he didn't want to, but because he knew in his heart that he couldn't accept it for them. Therefore, Song's tragedy is not a tragedy of Farewell My Concubine's identity, but more about power and the changes that people have to make when dealing with power. In the latter part of the scene, the cadre has a very interesting sentence: "Why do you still act like this when he is not here?" The implication is that when the power is absent, the identity is also vacuumed.

The final reversal and transcendence of the second narrative structure takes place at the end of the film, when Rene is sentenced for espionage and sees Song in men's clothing for the first time in court. In the prison car, Song approached Rene, completely lost his low-pitched expression, and replaced it with a mocking tone. The scene where Song insists on undressing in the prison van has a double meaning: if the perspective of racial criticism is still taken, this scene can be regarded as an allegory for the collapse of imperialism: the arrogant West finally sees the true face of the East for the first time, no longer weak and tired. , the mysterious "she", but the "he" in a suit and tie. No matter how you try to deny it, refuse to believe it, you must accept this fact after all. The second narrative structure is completely reversed, in which the East is able to get out of the relationship and the West is sacrificed for love. A natural reversal also occurs in gender power relations. It seems that the film also agrees: sometimes gender is also a kind of performance under the influence of social power. That's why the movie doesn't focus on whether Rene found out Song's true gender - it doesn't matter at all, what matters is whether Song treats him the way he is, wears robes and bows his head , and all sorts of mysterious, heterogeneous "feminine" actions.

But if you abandon all racial and gender perspectives, Rene is not an infatuated person. His love is idealized. He first created an oriental phantom, and then shaped this phantom on Song's body. From beginning to end, what he loved was his own imagination. From this perspective, all of us are no different from Rene. What we admire and despise in our dealings with people is not the projection of the self on the other. Here, we find that the story has returned to the original narrative mode, through inversion, irony, transcendence, and finally back to the original point - an ordinary love story. Whether it is really common or not is a matter of opinion.

[1] Opinions from director interviews. https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1Bx411s7fv?from=search&seid=13582688499414808454

[2] From director interview

[3] Become someone else is difficult to translate, meaning "to become someone else" and "to become (different from one's own) other"

View more about M. Butterfly reviews