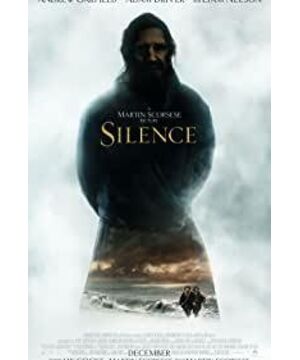

"Silence" from "What is God to Me"

Text/ Xing Fuzeng

Since the film "Silence" was released in Hong Kong, it has aroused extensive discussion. Since the subject matter of the film (and the original novel) has a strong religious (Catholic) color, how to understand and interpret the meaning of the faith expressed by the author Shusaku Endo has also become the concern of many Christians.

Recently, I found another book by Shusaku Endo that I bought a few years ago on the shelf - "What is God to Me?" (Translated by Lin Shui-Fu, Taipei: Lixu, 2013), this book not only allows us to understand the world of belief of this Japanese Catholic writer, but also explores its relationship with the Japanese Catholic writer through the three questions touched on in the book. The relationship between "Silence": (1) Endo Shusaku's belief, from doubt to hope; (2) His views on whether Christianity should wear "Western clothes" or "Kimono" in Japan; (3) Christianity of salvation and redemption.

In the book, Endo Shusaku reflects on his journey to becoming a Catholic. He was not born in a Catholic family, but his parents divorced, and his mother "probably wanted to use religion to ease the pain after the divorce", and was baptized under the guidance of his Catholic aunt. At that time, he and his brother "even though they didn't want to, they went to church with them," and they were also baptized later. "It was the fourth grade of elementary school, about eleven or twelve years old" (pp. 14-15).

Endo describes his beliefs as a "habitual" life (p. 18). Three of these beliefs have plagued him: One, about the existence of God. He said, "When I was young, I doubted the existence of God and read all kinds of books", hoping to prove the existence of this invisible God (p. 38). Second, when I was in the preparatory school at the age of 18 or 9, "after I started reading", I felt that Catholicism was a "Western religion" and had the idea of "throwing it away" (page 19). Third, he struggled with his beliefs. He realized that even though he had beliefs, he would still do bad things. He quotes another novelist: "Anyone has a secret that if someone else finds out, he might as well die...", facing himself "doing bad things" (p. 27), is a human being By nature, "you can't change anything on your own" (p. 28).

Belief in Doubt and Hope

Endo has never denied his doubts about God, "I even wanted to abandon God a few times." He quotes another Catholic novelist, G. Georges Bernanos, as saying, "Faith is ninety percent doubt, and ten percent hope" (p. 14). Describing his relationship with Catholicism, "I said get out! The other side won't go" (p. 19). The main reason for this is that his Catholic faith was inherited from his beloved mother, and he threw away the things that his mother cherished indiscriminately. Slowly, he became less obsessed with proving the existence of God:

Looking back on my past, there are many people who love me and support me. I feel that they do not exist randomly, but there is an invisible line linking them and supporting me in a role.… .. I call it the realm of the gods.

(pages 30 to 31)

This divine field is the role of God (p. 31), which he considers more meaningful than the existence of God. “So, how does God work on me? My condition works through my mother, or through someone very close to me in my life” (p. 39). He goes on to say that even in evil and sin there is a role of God (p. 33), including countless people who hurt themselves or who are hurt by themselves. All of this will "move" in the bottom of people's hearts at a certain time, but before it moves, it exists in the hidden places in people's hearts. Buddhism calls it "alaya consciousness (the deepest realm of the heart)", Christianity is "the place of the soul", and deep psychologists call it "the unconscious" (p. 40). As a Catholic, he was convinced that the soul is the heaviest part of man, and the place "in the depths of the heart" where God can take hold of man (p. 42).

When Endo Shusaku felt the "action" of God, he had a new understanding of what Bernanos said: "Faith is ninety percent doubt and ten percent hope; I am still There is only such a belief. Because it is still shaken even now. When something suspicious happens, there will be suspicion. However, there is still 10% hope to rely on. I don't know why I want to rely on it. Maybe it's because Inertia! Maybe fear! But it's not just laziness or fear, I think there's also a role for X." (page 51). This "X", to him, is "God" (p. 56).

Western clothes? kimono? Christianity and Japanese Society

Endo Shusaku felt that Catholicism was out of tune with Japanese culture early on. He described his mother as giving him "a very ill-fitting dress". Therefore, he was eager to modify the western clothes into kimonos that fit my body (page 20). The reasons for this situation include: (1) missionaries (whether Catholic or Protestant) in the past "forced" the image of Jesus from Europeans to the Japanese; What Western Christian scholars have learned from the West is a cold meal”; (3) The Japanese church did not seriously consider the Japanese problem and how to integrate Christianity into the Japanese. (pp. 129 to 131). As a result, in the eyes of the Japanese, Christianity is a "religion with a very narrow door", "a religion of judgment, a religion that often emphasizes sin, a superimposition of strict and dark religious imagery, which always feels very depressing" (p. 131). . It is not easy for the Japanese to become believers because Christianity is a "dress that is very uncomfortable to wear" (p. 137).

In addition, he mentioned an experience of being oppressed by Catholicism. In June 1950, he went to France as one of the first post-war international students to study French modern Catholic literature at the University of Lyon. However, he returned to Japan due to illness in February 1953 (pp. 235-236). In What Is God To Me? , he mentioned this experience:

I went to France as an international student shortly after the war and got sick there... I got sick like that because the ubiquitous Catholicism in the West oppressed me. the world, so my body became bad. I had a strong feeling that my body would recover just by escaping from there, so I didn't think deeply about Catholicism at that time.

(pages 21 to 22)

He did not specifically mention what the oppression in France was or what disease he suffered. However, there seems to be a connection between the two, and it is more vaguely revealing that he is suffering from mental troubles, so that he must leave France. Later, when he started writing novels, he "gradually understood that Catholicism is not just something in Europe. That is to say, I began to gradually understand that there are not only western clothes, but also elements of kimono (p. 24).

Through his novel, Endo hoped to "try to change this dress into a kimono that fits the Japanese body" (p. 163). He was convinced that the "image of the mother" was more suitable for the Japanese than the "image of the strict father's sanctions" (p. 132). He wrote "Women in the Bible", pointing out two different types of women: "extremely intense" and "sorrowful", and the Virgin Mary was "the synthesis, purification of these women" (pp. 106-122). In his book "The Life of Jesus", he expresses the image of Jesus with a religious consciousness of motherhood that is different from the fatherly religions of Western Europe. He believes that this is more in line with the Japanese-style religious consciousness (page 71).

sin and redemption

Under the Japanese culture that is deeply influenced by Buddhism, why did Endo not change his Catholic faith? He points out that the Japanese "think of faith as one hundred percent faith" (p. 25). In the Japanese view of religion, the purpose of religion is to purify oneself. To purify oneself, free from confusion, free from suffering, is called redemption” (pp. 168-169). The opposite of "purity" is "dirty", "sin" is "dirty", and good is clean. This is the basic Japanese concept of good and evil (p. 165).

He realizes that the Japanese concept of "salvation" is different from that of Christianity: "I have long suffered from the Japanese consciousness of the sin of Christianity" (p. 164). The Japanese 'goodness' is the holiness that 'must be pure' and the realm of 'no filth'. This is completely different from the Christian view of redemption, which despairs of redemption and finally attains redemption and liberation (p. 166). The result of Buddhist 'salvation' is 'silence'. The so-called cessation means to get rid of troubles and everything else, and go to the world of liberation in the world of samsara. This kind of "emptiness" and "transcendence", for Endo, lost the "dynamism of life" of Christianity. The so-called "movement of life" is the "great jump" of "participation in God's creative life" (pp. 180-181).

Endo's pursuit of the dynamism of life stems from his experience of sin. Because of the light of God, people are clearly aware of the existence of the "filth" (p. 195). However, Christianity's "Original Sin Theory" is not the Buddhist concept of "fate", but a "remaining hopeful" and "salvageable" theory of sexual evil (pp. 192-193). He emphasizes that being redeemable does not mean that Christians are perfect (p. 197). Christian redemption is actually a will that "recognizes that man is prone to sin" and yet believes that "God has redemption" (p. 193).

So 'devout Catholic' does not mean 'gradually abstaining from bad things'. He asks back, "Even in the end, you will do bad things, don't you?" (p. 50) So he has more tolerance for weak "betrayers." He saw that the Bible focused the betrayal on Judas. In fact, "all the apostles were Judas" to some extent. He rhetorically asked, "All are like Judas, aren't they?" (p. 61). They all faced Jesus with "the guilt of the betrayer". "Jesus taught 'love' in his own body during the agony of his final death. The disciples were greatly shocked to know that despite his suffering, he still embodied 'love'" (pp. 104-105).

He specifically refers to the confession of believers to priests in the Catholic tradition, "not strictly to the priest, but to God" (pp. 200-201). "What I did was forgiven by God, not by the priest," and after confession, the confessor "had an indescribable sense of joy and liberation" (p. 202). But Endo pointed out that confession is not as easy as imagined, especially when confessing sins in front of priests he knows, often with a "sense of humiliation", "a sin that feels very humiliating when you say it" (p. 202).

Behind the Silence...

The above has organized "What is God to Me?" from three aspects. "Endo Shusaku's belief world as seen in the book, and then discusses its relationship with "Silence".

God's "Role" in Silence

Regarding the creation of "Silence", Endo mentioned a period of his illness. In 1960, he was admitted to Dongda Chuanyan Hospital due to tuberculosis, and transferred to Qingying Hospital at the end of the year. In 1961, his condition deteriorated, and he underwent three surgeries for his lungs. He was discharged from the hospital in July 1962, but his strength has not yet recovered (p. 238). The experience of illness made him regret that his creations were affected. Later, due to hospital expenses and failed surgery, he felt that he had reached a dead end (pp. 22-23). At the same time, he once again experienced a crisis of faith:

When I was sick and hospitalized, I saw children in the hospital, and I doubted God. Some children are born without hands or feet, saying they have only three months to live. Why should innocent children suffer so much, I pondered. At that time I doubted God's love, which was revealed in "Silence".

(page 52)

The contradictions and tensions arising from doubts about God's love are fully presented in "Silence" through the persecuted Catholics. "Why did the Lord give us so much pain? Father! We didn't do anything bad!" Endo wrote in response to questions from Japanese believers: "We were silent. Mokichi and Izo also stared silently at the void. We sang the last prayer for them in unison. After praying for the kitchen, the three went down the mountain." ("Silence", p. 66. Translated by Lin Shuifu, Taipei: Lixu, 2002) "Prayers" can really fill "" The emptiness of silence? The two priests had no choice but to watch the three of them go down the mountain and embark on the road of "martyrdom" or "abandonment".

The silence in "Silence" often has great tension. For example, when Mokichi and Ichizo were martyred, Endo wrote: "God and the sea remain silent, keep silent". In Father Lotrigo's heart, the question "In case there is no word of God..." appeared. He said, "I know that the greatest sin is despair of God, but I don't understand why God is silent" (Silence, pp. 81-82).

Does God's Silence Deny Faith? Endo injects his own experience from doubting to believing, and feeling the role of God in an invisible God, into the novel. Undoubtedly, Father Lotrigo finally abstained from the church, but Endo also expressed that the priest still believed in doubt. Father Lotrigo saw the face of Christ and heard the voice of Christ during his "stepping painting": "Go on! It doesn't matter if you go on, I am here for you to trample on" (Silence, p. 213) . After his abstention, he remembered the face of Christ again and heard "Go on! Your feet hurt now... I share your pain, I exist for it". The priest said, "Lord, I hate you for being silent all the time." Christ replied, "I am not silent, but suffer together." Finally, Lotrigo said:

Even if I betray them (by the author: referring to the clergy of the Catholic Church), I will never betray him. I love that person in a different way than before. All that has been done up to this day is necessary in order to understand His love. I am still the last Catholic priest in this country. However, that is not silent. Even if that person is silent, as of today, my life itself is talking about that person.

("Silence", p. 229)

Endo Shusaku in What Is God To Me? ” said: “I once felt a hand behind me with something invisible to my eyes, pushing me to this side. That is, I felt the effect of God. Finally write it out.” (page 31) “At the end of Silence, I wrote 'Through your life, I speak, so I am not silent', what I want to say is that I want to prove that God is in X role. That line is very important to me....” (p. 44)

Obviously, Endo expressed his experience of the role of God through Father Lotrigo:

My life is a lot of people who pushed me here. And behind this pushes me, there is a force invisible to the eyes that brings me here. If I wasn't Catholic, I probably wouldn't be able to get to France. In France, I met people that I don't usually meet. Furthermore, if it wasn't for the three-year serious illness, I might not have been able to write the novel "Silence" about God. Thinking like this, I have to admit that there is a force that cannot be seen by the eyes. For me that's what the Holy Spirit does.

(page 191)

It can be seen that the writing of "Silence" was derived step by step from Endo's life experience. But at the same time, he further realized the role of God by writing "Silence":

I understand that through many people, I realize that it is a force that is invisible to my eyes that pushes my life from behind, and that I am what I am today, and it is God who pushes me from behind. "Don't think of life as just one's own life. It is the place where many people gather together from parents, and you can stand up. ...... This is what I wrote "Silence" I slowly realized it later.

(page 45)

Catholics in Kimono

Another concern of Endo Shusaku's creation of "Silence" is to reflect on the tension between Catholicism and Japanese society and culture. The aforementioned experience of illness during Endo's stay in France has already felt the oppression of Catholicism. Later, he realized that Catholicism is not just a European thing, but in Japan there can be "elements of kimono". So, "I began to think about incorporating it into my own work. The novel "Silence" written after I was discharged from the hospital has such a thing (page 24).

In "Silence", Lotrigo's dialogues with the translators Zhuhou Shoulu and Ferreira successively show this tension.

The former Japanese interpreter questioned the priest: "Forcing people what they don't want is called forced gift giving. Catholicism is very similar to this kind of forced gift giving. We have our religion and we don't want to accept foreign ones. Religion.” (Silence, p. 106) he adds: “The priests have always looked down on us Japanese”, “despite people coming to Japan and laughing at our houses, at our language, at our food and habits "Even if we finish seminary courses, we will never be allowed to be priests." ("Silence", p. 106) The Eurocentric image of Catholicism in the Japanese mind is fully expressed here.

Later, the interpreter used trees as a metaphor for Catholicism. "A tree that blooms and bears fruit in a certain place may wither if the place changes. A tree called Catholic has luxuriant branches and leaves in a foreign country and still blooms, but in Japan, its branches and leaves wither and there are no flower buds. The priest did not think about it. The problem of acclimatization.” (Silence, p. 133) In the end, what was the reason why Catholicism could not take root in Japan?

Later, Ferreira, who abandoned the church, used his "failure" in his 20-year missionary work in Japan to explain that Catholicism is not suitable for Japan. This is what he confessed to Lotrigo: "I have been a missionary for twenty years!" "I have learned that in this country you and our religion can never take root." "This country is a swamp. You will understand soon too. This country is a more terrifying swamp than imagined. No matter what kind of seedlings are planted in the swamp, the roots begin to rot and the leaves turn yellow and wither. We planted saplings called Catholicism in this swamp.”

Ferreira pointed out that the core of the problem is that Japanese culture cannot accommodate Catholicism at all, and in turn distorts the Catholic faith: "The people of this country, at that time, did not believe in our gods, but their gods. For a long time, we didn't know this fact and mistakenly thought that the Japanese had become Catholics." "And I only got to know the Japanese after 20 years of preaching, that the roots of the saplings we planted were gradually rotten without knowing it." "The gods they twisted in their own way are not our gods" . "What they believe in is not a Catholic God. The Japanese did not have the concept of God before, and they will never have it." Ability". "The Japanese call people who have been glorified and exaggerated as gods. They call things that exist as people as gods; but that is not the god of the church." He concluded: "Therefore, I think that preaching is meaningless. The seedlings that came here, in this swampy land called Japan, have at some point rotted their roots." ("Silence", pp. 179-183)

For Endo Shusaku, the only failure may be to wear Catholicism in a sense of "foreign clothes". In fact, "Silence" also mentions Catholicism with the characteristics of "kimono". For example, Japanese officials asked Mokichi and others, who had already painted, to spit on the statue of the Virgin, and scolded the Virgin that it was ridden by a thousand people. Fr Lotrigo found that "the most worshipped of the poor people of Japan is the Virgin", and sometimes they "revere her more than Christ" (Silence, p. 68). Isn't this exactly the "Kimono" Catholicism that is in line with Japan's religious consciousness as described by Endo above?

In addition, in "Silence", a female believer named Monica expresses her firm will to the impending death, which originally came from her expectation for a "kingdom of heaven" without suffering ("Silence", p. page 99). And Moji, who was martyred by the sea, finally sang "Go! Go! Go to the church of heaven! The church of heaven; the church far away..." ("Silence," p. 71) . These, all became Father Lotrigo's firm response to Ferreira's denial of the faith of the Japanese believers: "Impossible, that's impossible." Endo wrote:

Such a thing is impossible! One cannot sacrifice oneself for false beliefs. The peasants and the poor martyrs I saw with my own eyes, if those people did not believe in redemption, how could they sink like stones in the drizzling sea? Those people are all believers and believers with firm beliefs, no matter which angle they look at! That belief, though simple, was instilled not by Japanese officials or Buddhism, but by the Church.

("Silence", p. 185)

Even Father Lotrigo's apostasy was only a "submission". "Lord! Only You know that I am not truly apostate ("Silence", p. 212). Wouldn't this be the exact opposite of Endo's claim that Japanese Christians are all living a double life and compromise appropriately (p. 127). ?

After "abandoning religion", Father Lotrigo met with the first time, Endo described, "now he has no sense of shame for the man in front of him." Because Father Lotrigo knew that he was not fighting against the Japanese who persecuted Catholicism, but "his own faith". When Fengcheng said to him, "The priest didn't lose to me...it was to the swamp called Japan." He replied loudly, "No, what I'm fighting against is the one in my heart. Catholic Doctrine". ("Silence", pp. 222-223) What he was referring to was both the "dressed" Catholics and the "vanity" Catholics who thought they could strictly abide by the precepts (p. 206).

In "Silence", on the one hand, we see the "failure" of the Catholicism of the "Yofu", but on the other hand, Endo seems to be asking, "Can the Catholicism of the "Kimono" really take root in this swamp?

apostate

Endo Shusaku's thoughts on sin and redemption in faith can also be seen in the tension of apostasy in "Silence". In What Is God To Me? " in which he confessed his understanding of martyrdom and apostasy when he wrote "Silence".

When he conceived of "Silence", he went to Nagasaki to see "Treadmill" and "Hell Valley". Facing the scene of the past, he couldn't help asking himself: "I think martyrs are great. But can I be martyred? I don't have self-confidence." the one who went down"? When he saw Takao, he thought, "What kind of person stepped on? What kind of mood did he go in?" and asked himself again, if he was in that situation, "Would he have stepped on it? He said, "I was obviously the one who might step on it, so I put the camera on the person who stepped on it." (p. 208) When he visited Hell Valley and thought that he was also tied to it, he knew that he might Immediately "passed out!" This made him even more aware of where to place the camera when he wrote "Silence" (p. 209).

Therefore, "Silence" has a profound description of the mental journey of the apostates. For Father Lotrigo, when he felt the Latin "LAUDATE EUM" (Lord! Praise You) engraved on the wooden wall of the prison, he thought that it was left by a strong and unabandoned missionary. . But then Ferreira, who abandoned the church, told him that this was what he wrote: "I abstained because, please pay attention! Later, when I was locked up here, I heard the moan in my ears, but God didn't say anything at all. I prayed desperately, but God said nothing" (Silence, pp. 194, 202). Fei Geng forced Luo repeatedly: "If you say you apostate, those people can come back from the cave and be rescued from their pain." "Priests must learn to live for Christ, and if Christ is here... Christ will apostate for them!" "Christ will apostate! For love, even at the expense of himself."( "Silence", pp. 204-205)

Ferreira's apostasy, because he prayed desperately but did not see a miracle from God. Endo Shusaku in What Is God To Me? " also expressed his understanding of "miracle". He said, "There is a child, and the child is suffering from cancer. Of course, parents will pray, "God! Please, please help me!" If they still die, they will think that there is no miracle. There is neither God nor Buddha, right? However, true religion begins here." (p. 91) What does "true religion begin here" mean here? What Endo wants to express is love. No doubt Jesus performed miracles of healing and even raising the dead, but most importantly, Jesus performed miracles out of love. "Without love, there is no miracle of Jesus". Therefore, what is done by the power of love is a miracle (p. 92). In reality, there are greater miracles than curing diseases, "to die for others by the power of love is also a miracle" (p. 89). The power of love is the beginning of religion. And Father Lotrigo is hearing the voice of Christ, "Go on! I was born to be trampled on by you, and I was born to bear the cross to share your pain." That's it, he put his foot on the icon. ("Silence", p. 207) Yes, there are no earth-shattering miracles that do doubt the existence of God. But isn't this another miracle that this seemingly silent God taught priests love for the suffering at his own sacrifice?

Different from Father Lotrigo's apostasy, in "Silence", Yoshijiro is a person who has made many decisions to apostate. Endo pointed out that he was intentionally highlighting Yoshijiro's decision to make a "tae-e", "If you ask him what would happen if he stood in front of the 'tae-e'? You can probably understand why Yoshijiro appeared in "Silence" (p. 210). ).

Interestingly, every time Yoshijiro gave up his religion, he would come back to the priest to confess his sins, hoping to obtain God's atonement. "I, I can't be that strong!" "My foot hurts! It really hurts! I was born weak, but God wants me to imitate the strong. That makes no sense!" "I want Confession, please, I want to do a confession that restores faith” (The Silence, pp. 138-139) “Father, please forgive me! I came here to repent, please forgive me!” (The Silence , p. 197) Even after Father Lotrigo "abandoned", Yoshijiro went to see him, "Listen to me, if Paul, who apostates, has the ability to hear confession, please forgive me for my sins!" ("Silence," p. 227) Yoshijiro's role is fully explained: Christ is "the God of love and the God of forgiveness", "God said that no matter what the past, the one who truly repents in the end can be saved." (page 232)

At the end of "Silence", Endo clearly pointed out through "Diary of a Catholic Residential Official" that Father Lotrigo and Yoshijiro still adhere to the Catholic faith, and that Catholicism is also showing signs of resurgence. In What Is God To Me? " said:

The last official diary of "Silence"... Kiziro was imprisoned, the protagonist Lotrigo said that I still believe in Catholicism, and was tortured and forced to write a certificate of abandonment. ...... What I want you to know in my diary is that Lotrigo went to prison, gave up his religion, and then reverted to his Catholic status. Yoshijiro, the coward, escaped after being released from prison, but he returned to the prison and dangled.

(page 210)

Perhaps this is Endo Shusaku's own monologue: "I think I'll give up my religion, revert to my faith, and step on it again and again! I think it's still faith. I don't think it's a great faith; but , my faith is that degree.” (pp. 210-211)

Endo has always believed that "if people are so strong, they don't need religion" (p. 25). It is precisely because he has a deep understanding of the weakness and struggle of human nature that people need religion.

monument of silence

In November 1987, Endo Shusaku participated in the unveiling ceremony of "Monument of Silence" in the Endo Shusaku Literary Museum in Nagasaki. Inscribed on the stele is his inscription: "Humanity is so sad, Lord! The sea is so blue."

We must compare this inscription back to the most harrowing scene in The Silence. It was the priest who witnessed the martyrdom of two brave believers and heard the shock of the tsunami in the night - "The sound of the waves in the darkness was as low as a drum; all night, a senseless shock, back down, back down The sound of crashing again. The waves wash indifferently, swallowing the bodies of Moji and Izo, and after they die, the same expression expands in the sea, while the god and the sea remain silent and remain silent.” (The Silence, p. 81 ) Behind the strong martyrdom, the silence of God is highlighted...

In the darkness, huge waves hit again and again, and it seems that human beings have never been able to get rid of their sad fate. Believers continue to experience doubts about this, but God remains silent as usual. Ninety percent doubt, however, cannot negate ten percent hope, and "that ten percent may be stronger than ninety percent" (p. 53). Faced with a sea where huge waves devoured confidence, Endo said, "If you think of your life as the ocean, you feel that you are supported by something in the ocean. I feel that it is God who surrounds my life." (p. 191) Although God is silent , but still with the sufferer in the midst of suffering.

Humanity is so sad, Lord! The sea is very blue

──Endo Shusaku

View more about Silence reviews