By: Louis Menand / The New Yorker (April 5, 2021)

Proofreading: Qin Tian

The translation was first published in "Iris"

In December 1963, Life magazine published a special issue on "Film". The magazine asserts that the US has fallen behind the rest of the world. Hollywood is too timid and too worried about the "image" of the country. Meanwhile, filmmakers in Sweden, Japan, Italy and France are making films that people will talk about. The magazine concluded: "While the entire film industry is busy with new excitement, Hollywood is as lost as Chaplin on the doorstep of a millionaire."

A full four years—presumably after the production cycle of a feature film passed, almost overnight, Time, Life’s sister publication, published a cover story about the “new film.” “The most important fact about the screen in 1967,” it declared, “is that Hollywood has finally become part of what the French film magazine Cahier du Cinéma calls the ‘spring of world cinema’s rage.’” How did this all happen? How Hollywood went from losing millions on flamboyant blockbusters like Mutiny (1962) and Cleopatra (1963) to suddenly turning to productions like The Graduate (1967) and Bandit (1967) such impressive films—how “Old Hollywood” became “New Hollywood”—is a hot topic among film historians.

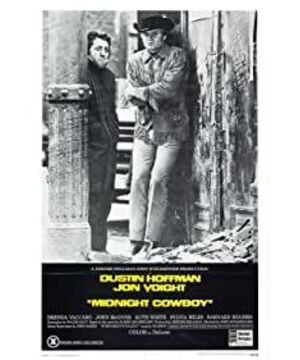

Midnight Cowboy is often left out of this discussion. When it hit theaters in May 1969, "Midnight Cowboy" seemed as fresh, as surprising, and as "must-see" as "The Graduate." But it's not even mentioned once in Robert Sklar's "Film Making America: A Cultural History of American Cinema." In Peter Biskin's "Easy Rider, Raging Bull: Inside the New Hollywood" and Mark Harris' "New Trends Movies: Five Movies and the Birth of New Hollywood" (tentative translation, Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood), the movie appears a few times, but only incidentally.

Glenn Frankel's new book Shooting 'Midnight Cowboy': Art, Sex, Loneliness, Liberation, and the Making of a Black Classic Making of a Dark Classic) aims to change all that. "More than fifty years later," Frankel argues, "Midnight Cowboy is still a somber and disturbing work of fiction and film that far surpasses most other books and books of the era. Film." Frankel's book has a rich background, but is essentially a biography of a film. He has also written books on The Searcher and High Noon. These works have the same interest as celebrity biographies: they show us the "ifs" and "what ifs" hidden behind the finished product.

There are far more films that haven't been made than have been made: too many elements are needed to do one thing, and too many elements can go wrong. Filmmaking requires creative people to collaborate under constant pressure to control costs and turn a profit. In a game where everyone has their own ideas and millions of dollars keep pouring in, it's inevitable that things won't go exactly as planned.

It's no surprise, then, that "Midnight Cowboy" director John Schlesinger had trouble securing studio financing, and the failure of his previous Julie Christie film "Far from the Hustle" was even more so. To make matters worse. Including the fact that he initially thought the book on which the film was based was difficult to read, and that he didn't originally like the cast of these two actors: Dustin Hoffman as Rizzo, the Times Square underclassman, Jon Waugh Te's character is Joe Buck, a naive Texas boy who tries to come to New York to hook up with a rich woman, and ends up taking care of Rizzo.

Both Robert Redford (who also wanted Hoffman's role in The Graduate) and Warren Beatty lobbied for the role of Joe Barker. An executive at MGM declined to make the film, but recommended Elvis Presley, who was later offered the role by Michael Salaz, who signed the contract asking for an increase , this cooperation also came to an end. The casting director Marion Doherty, who was responsible for getting Hoffman and Water on the project, was not named on the credits.

Aside from Hoffman and Walter's performances, what most people remember from the film is Harry Nelson's performance of "Everybody's Talkin'." Frankel said that Nielsen didn't actually like the song and only covered it while recording the album as a favor to the producers. There could have been other outcomes at the time: Leonard Cohen sang "Bird on the Wire" to Schlesinger on the phone, and Bob Dylan wrote a song for the film. A song, probably "Lay Lady Lay," didn't make the cut because he submitted it too late. There's one more thing everyone remembers, and this line is taken to heart by every New Yorker -- "I'm walking here!" It wasn't written in the script, it was Hoffman's improvisation.

The screenwriter Waldo Short, who was hired to adapt the novel, was another gamble. He was blacklisted and rarely wrote under his own name for 11 years. He was 52 at the time and hadn't been involved in any famous Hollywood movie since the 1940s.

The film's editor is Hugh Robinson. Schlesinger didn't get along with him; producer Jerry Hellman called him a "disaster." And Robinson was dismissive of what Schlesinger photographed. He thinks what he's photographing looks foolish, like a tourist's view of New York. (Schlesinger is British.) Finally, Schlesinger brought in Jim Clark, an editor he had worked with, to deal with the mess Robinson had caused his film.

"The Graduate" made Hoffman a women's icon. Female fans surrounded him. But he felt that audiences thought he was just being there in that movie, so he wanted to play the role of Rizzo so much that he could show his breadth as an actor - despite The Graduate director Mike Nichols He was warned that it would ruin his career. Hoffman got No. 1 on the casting list, but was pissed when he realized that Walter was the focus of the film. He complained that Schlesinger cut out a scene he was particularly proud of. He did not attend the promotional event. The producers denied his claims.

But the end result is great. "Midnight Cowboy" grossed nearly $45 million on a budget of just under $4 million. The film won Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director. Hugh Robinson was nominated for Best Editing and Waldo Short was nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay. "Everybody's Talking" catapulted Harry Nelson to No. 6 on the Billboard charts and sold millions of albums. The film didn't ruin Dustin Hoffman's career, he and Watt were both nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor, however, the award went to John Wayne, who made "Midnight Cowboy" Called "A Tale of Two Gay Guys (fags)".

Of course, Midnight Cowboy is not a story about "two gays." But somehow it was quickly associated with a new era of gay candor, reinforced by the fact that it had nothing to do with it, the rock that erupted a month after Midnight Cowboy came out. Wall Riots - This is often seen as a sign of the beginning of the gay liberation movement.

This connection is important to Frankel, who watched the film in the context of "the rise of openly gay writers and gay liberation." Mark Harris said in a note on the Standard Collection CD that Midnight Cowboy "is, if not a gay movie, at least a movie that makes the concept of a gay movie possible." They're both right, But this is a tricky case.

Granted, "Midnight Cowboy" is about two men developing a relationship under difficult circumstances, but so is "Tiger and Leopard," which came out in the same year -- it's also a potent Best Picture Oscar winner. competitor. You can decipher gay elements from sibling films like this, where women are often seen as accessories. But no one thought that such a film would allow audiences to see gays in a more enlightened way.

Frankel believed that Schlesinger's own gay identity was important. But, as he admits, this is not well-known common sense. Schlesinger, who didn't come out publicly until the 1990s, said he didn't think "Midnight Cowboy" was a "gay" movie. In his next film, Bloody Sunday (1971), Peter Finch played a sympathetic gay character. But there is no such character in Midnight Cowboy.

Joe and Rizzo have little sympathy for gay people, and they often use what John Wayne calls "gay." According to Schlesinger's biographer William Mann, Hoffman thought his character should also use swear words, but Schlesinger was horrified and refused to let him do it. He doesn't mind the homophobic insults, though. Years later, he claimed that the character's use of the term was a "symbol of excessive protest," which in hindsight seems like a valid reason.

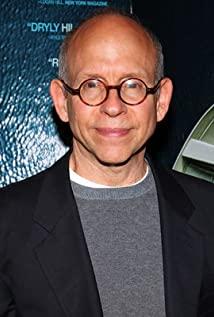

There are very few gay characters in the movie with lines. One, played by Bob Balaban, is a brash teen who has an affair with a visibly disgusted Joe at a Times Square movie theater, after which he admits he doesn't have the money to pay him. The other is a self-hating middle-aged man (Barnard Hughes) who gets Joe into a hotel room and offers to be beaten, which gets him excited.

The female characters have longer scenes, but their images are almost all sex-hungry. A set of party shots in the film should have been similar to scenes in Andy Warhol's "Factory" studio ("Midnight Cowboy" was filmed in June 1968, when Warhol was shot), But then it evolved into a psychedelic montage of sloppy-looking characters doing sloppy things (and taking a lot of drugs). The presentation of sexuality in the film is obviously intended to arouse people's disgust.

The same goes for the novel—the original author, James Leo Herrihan, is also gay, but he doesn’t want people to think his 1965 book is gay. There is no suggestion in the book that Joe and Rizzo are self-denying gays. The greatest influence on Heriham's novel was Sherwood Anderson, who called the characters in his most famous work, Winesburg, Ohio, "grotesque." This is also the way Herrihan sees the world. “To me, living on this planet is a gothic and grotesque experience,” Frankel quoted him as saying in an interview. "It's a scary place. We don't think he's completely normal."

This is the worldview that Schlesinger and Schott aim to capture. Except for the Don Quixote/Candidian character, Joe Barker, everyone in Midnight Cowboy is creepy. When Pauline Kael (who hated Schlesinger's work) complained of "inaccurate and unpleasant irony," she was probably watching a movie through the other end of the telescope. This is what it's like to live at the bottom.

Whatever effect Midnight Cowboy had on gay attitudes, it had a negative effect on New York City attitudes. The film was shot in Texas and New York. (Schlesinger had originally planned to shoot the black and white version—another "if not" left to the imagination.) The photographer was also a serendipitous discovery—Adam Holland, a 29-year-old Polish man recommended by Roman Polanski . This is his first feature film. To the distress of the experienced film crew, Holland insisted on shooting the film in as much natural light as possible. The result is a gritty style of realism that we don't see in films like "Hands and Hers" and "The Graduate." In 1969, it was still a shocking cinematic experience. It makes Times Square look like a scene from Dante's Inferno.

This also seems to be Robinson's part against Schlesinger. But New York in 1968, the year the film was made, wasn't exactly "Easy City." For many, as Frankel reminds us, it seems moribund. From 1960 to 1970, crime tripled. In 1968, there was a strike by teachers, sanitation workers, fuel delivery workers and fuel supply workers. The city was heavily indebted; in 1975, it was on the brink of bankruptcy. The emblematic center of urban decay is Times Square, which, as Dick Nezel — a financial adviser to several New York mayors — is “the worm in the Big Apple.”

A decade or two after it was named after The New York Times in 1904, Times Square began to enjoy its reputation as a bohemian enclave. In the 1940s, the beat generation — Allen Ginsburg, Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, Herbert Hank — haunted here. In the 1950s, when movie theaters were open late and admission was cheap, people would go there to see multiple movies. Broadway is still thriving.

By 1960, however, the area's population had dwindled significantly. That year, the headline of a New York Times story was "Living on 42nd Street: A Study of Recession." (In 1913, the paper moved to 43rd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, but kept an eye on the neighborhood, often critically.) Important upscale venues began to disappear. The Paramount Theater closed in 1964, and the Astor Hotel closed in 1966. The following year, the old Metropolitan Opera House was demolished, which, for some New Yorkers, was the equivalent of the 1963 demolition of the old Penn Station.

In his book on the history of Times Square, The Devil's Playground (2004), James Traub wrote: "In the early 1960s, Times Square had become the center of male prostitution in New York." The area is littered with voyeur houses, massage parlors and pornographic bookstores, and crime rates have risen with it. The most notorious places are Seventh and Eighth Avenues, but even Bryant Park is packed with pimps and drug dealers. People avoid walking through these neighborhoods, day or night. (A movement to save the theaters began in the 1970s, eventually saving several Broadway theaters from being razed. It wasn't until the 1990s that the Disneyization of the Times Square area really began.)

In the end what happened? The decline of 42nd Street was related to changes in the film industry (fewer feature films were released due to competition from television, and movie theaters closed) and Broadway theaters (due to declining box office receipts, causing theaters to close). But Traub believes a key factor is the loosening of legal restrictions on pornography and sex work.

Obscene has always (and still is, strictly in the legal sense) not protected by the First Amendment. However, beginning with Kingsley Pictures Corp. v. Regents in 1959, the definition of obscenity became narrower in a series of Supreme Court decisions. It's getting harder and harder to prove in court that things like pornography or naked dancing should be banned.

Then there were raids, and police harassment, but they didn't drive away the mill cinema, voyeur house, softcore store, or their patrons. The extent to which decisions about obscenity are tolerated, and the societal trends they conform to, help widen the range of behaviors that are protected by law or ignored by officials. The unrest outside the Stonewall bar in the West Village was the result of routine police harassment. To the police's surprise, this time the customers resisted. They must feel that history is on their side.

However, this is only half of the story. The other half happens in the cultural industry. In 1963, when Life magazine bemoaned Hollywood's timidity and preoccupation with the nation's image, it was actually criticizing the Hays Code — a highly restrictive rule dating back to the 1930s that stipulated what a Hollywood movie can show. The Supreme Court's decision in Kingsley, as well as Grove Press v. Gerstein (allowing the publication of Tropic of Cancer) and Jacoblis v. Ohio (another film case), are clear The Hays Code is a huge burden on the film industry, as it is clearly shown. Movies are losing audiences. They have become unfashionable.

So when Jack Valentine became president of the MPAA in 1966, his first task was to replace the code. This was officially done in 1968, when the Motion Picture Association of America adopted the rating system. If the time goes back five years, no company can release "Midnight Cowboy". For decades, the code even banned the use of the word "homosexual". Schlesinger and Hermann bet that by the time their movie hits theaters, the rules will have changed.

They got it right. Mike Nichols and Arthur Payne also got it right. That's why, as the turtle put it after being attacked by a pack of snails, things happened so "fast". Filmmakers saw, as Life magazine saw, that a new kind of Hollywood movie was about to be born. When that moment came, they were ready.

"Midnight Cowboy" is often cited as the only X-rated film to win a Best Picture Oscar. In a way, this means that in 1969 the MPAA still boycotted certain subjects, which is misleading. In fact, according to Stephen Farber's 1972 book The Movie Rating Game, the jury gave the film an R (almost on par with today's R). rating), but Arthur Crim, the owner of United Arts, which made the film, had the film rated X. Kerim worries that younger audiences may have the wrong idea about sex. This is the attitude that Life magazine refers to.

From a business perspective, this is a stupid move for United Arts. X-rating reduced the number of theaters willing to show the film — even though from the start, people were lining up to see it. After the Oscars, United Arts asked the rating board to re-evaluate the film, which was given an R rating. Since then, more theaters have been able to show the film.

In other words, changes in the legal environment regarding the film industry and artistic expression contributed to the decline of Times Square and the rise of New Hollywood. As Frankel and Harris say, when Hollywood sees the success of Midnight Cowboy—a film that is candid about homosexuality, even if it presents it as a dirty pursuit, you can more easily Sell a movie that features homosexuality in a normal way. Whatever John Schlesinger set out to do, he helped open up a new cultural space.

Original link:

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/04/12/the-making-of-midnight-cowboy-and-the-remaking-of-hollywood

View more about Midnight Cowboy reviews