By Rahul Hamid / Senses of Cinema (April 2005)

Proofreading: Issac

The translation was first published in "Iris"

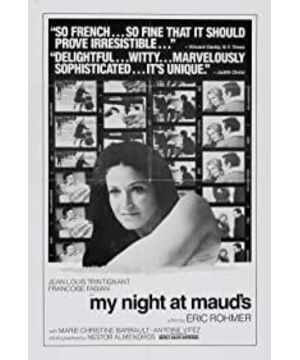

Often, Eric Rohmer is introduced as an elder of the French New Wave, implying that his quiet, talkative, poised style is less aggressive or distant than other important members, such as Claude Chabs Lohr, Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut and Jacques Rivette. We often associate the movement with an unconventional style, with films shot on location, often on the streets of Paris, full of classic sayings heralding the young men who would dominate Western cultural life in the 1960s The political and emotional advent of a generation. Part of the reason may be that Truffaut and Godard were the most famous New Wave directors, and their styles defined the movement in some ways. Indeed, Rohmer's 1969 breakthrough, One Night at the Mauds, was a far cry from these films. However, it is a rich and satisfying work that is a pleasure in itself and contributes to a fuller understanding of the New Wave.

Much of the intellectual foundation of this movement can be found in the film review articles published by Cahiers du Cinéma, whose editors have mostly become the standard-bearers of the New Wave, such as Truffaut's 1954 article entitled "The French Cinema". A Certain Tendency", a poignant statement on the current state of French cinema. Another important and influential article was "The Birth of a New Pioneer: The Camera Pen" by Alexander Aschuk in 1948. Aschuk believes that cinema should become a more casual and personal form, in which the camera acts like the director's pen, the "camera pen". Truffaut also referred to the unoriginal nature of the prestigious, "traditional" French studio films. He points out that the scripts for these films are often tedious adaptations with formulaic, anti-church and anti-bourgeois messages, hypocritically written by extremely bourgeois screenwriters. Truffaut believes that films should be more nuanced, with either a director-written script or a more novel adaptation that allows for a more honest treatment and portrayal of middle-class life and beliefs. They believed that films should be personal, able to touch on the intangible, mystical aspects of human existence. Although One Night at Maud's came after the most influential years of the New Wave movement, the film perfectly embodies these ideas and sensibilities and fits the New Wave style very well.

The film opens with engineer Jean-Louis (Jean-Louis Trentignan) driving from his home to a Christmas Eve Mass at a church in Clermont-Ferrand—he has recently been transferred to work in a province. While he's praying, he notices a blond woman (Marie-Christine Barrott), but doesn't approach her. After the service, he meets his high school friend Vidal (Antoine Witez) and joins him for dinner. Later, Vidal mentioned that he wanted to visit his friend Maud. Maud is a newly divorced mother (Frances Fabian) who is a pediatrician. Vidal, obviously fond of Maud, encouraged Jean-Louis to spend the night with her. Jean-Louis initially refused, but ultimately decided to stay. Maybe Vidal was trying to find an excuse to hate her, or was testing her. It's one of many questions about love that the film asks.

At dinner with Maud and Vidal, Jean-Louis claims to be no longer interested in the occasional affair, expressing his strong Catholic faith and a desire to settle down and marry. Jean-Louis, who has recently begun re-reading Blaise Pascal's work, links his situation to the 17th-century philosopher's famous bet that it is logical to believe in God, because if "He" doesn't exist, you believe God has little to lose, and if "He" exists, you will reap a lot. From a religious point of view, this wager is unsatisfactory because it does not require true belief; it is just luck. Pascal was a Jansenist - a sect affiliated with the French Catholic Church, who believed that redemption can only be achieved by the grace of God, and that it is doomed, regardless of our actions. Contrary to the Jansenists, the Jesuits advocate an active pursuit of the noble life in order to enter heaven. Jean-Louis thinks he's following Jesuit teachings, but the scene at Maud's house is all about verifying that's true. One Night at the Mauds is the third installment in Rohmer's "Six Moral Tales" series, each of which explores the philosophical and moral conundrums surrounding love and contemporary life.

The film isn't just about Jean-Louis's self-deception or an admissions test of male self-control. Maud isn't just a screenwriter's tool either; she's a character who knows everything. It was Maud's honesty and ability to see clearly what was going on that drew attention to the way Jean-Louis hypocritically expressed his subjective feelings in abstract, rational, and culturally-approved terms. Rohmer's precise and natural dialogue reveals the characters' philosophical positions as well as their weaknesses, contradictions and hopes. The film's energy comes from the looming hope of happiness -- the foundation of all the characters' actions, but still out of reach. Rohmer captures the excitement and anticipation, as well as the caution and fear that accompany our decisions about love, giving the film an unexpected sense of urgency and suspense. After Christmas Eve, the plot continues as we see the outcome of Jean-Louis and Maud's choices, and the bittersweet tone continues, ending with an echoing melancholy and rather bitter irony.

Rohmer's method is often called literary. The way he weaves moral philosophy and quotations from various sources into the discourses of film characters is reminiscent of Dostoevsky, or other 19th century novelists. Rohmer's insistence on realism and naturalism in dialogue and scenes makes his films exceptionally cinematic. He combined his intellectual interests with a careful examination of everyday life. We can see this in the winter scene of the common streets of Clermont-Ferrand - shot by the great photographer Nestor Almendros (who was Rohmer's photographer in office and also responsible for the Thai Photography by Lance Malick, 1978's Days in Heaven). He captured the unnatural stillness of city streets in the snow and the slippery grey roads covered in silt. In all great movies, when no one is talking, what we see and hear is as important as the storyline that happens. The charm of this film is that it moves forward with a charming lightness, telling its story without being overly intellectual or exaggerated; it makes us believe and feel its characters, even when we may be intellectually Analyze and dissect their behavior. Compared to Godard's films, "One Night at the Mauds" is rather bland. However, the clarity of Rohmer's vision is almost the same as the intelligence and intensity he brings to the subject of the film, and the questions he wants to ask.

Original link:

https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2005/cteq/my_night_at_mauds/

View more about My Night at Maud's reviews