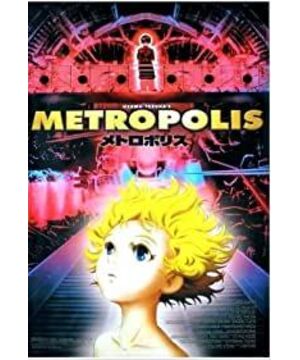

★★★★ (out of four stars) There's something about the sprawling city of the future that excites me. Maybe they evoke memories of when I was 12, sitting in the basement on a hot summer day, reading through science fiction magazines: Imagination, Another World, Amazing Stories. On the cover, towering cities are connected by sky bridges and buses are cigar-shaped rockets. In the foreground, a monster with bulging eyes is attacking a screaming heroine in an aluminum bra. Even now, the image of a spaceship tethered to the top of the Empire State Building is more exciting to me than the space shuttle, which is just real. These ideas are silly, but at the same time exciting. I love Tokyo because it looks like a 1940s vision of the city of the future. I put Shifting Souls at the top of my list of the best movies of 1998, I love Blade Runner's visuals more than its story, and I love The Fifth Element's air taxi. Now it's Metropolis, one of the best animated films I've ever seen, and the city in this movie isn't just a setting or location, it's implanted in our memory. Named after Fritz Lang's 1926 silent film classic, the Japanese animation is based on a 1949 manga by the late Osamu Tezuka and includes images of Lang. The film is directed by Rintaro and written by Japanese animation legend Otomo Katsuhiro, who directed Akira and wrote Old Man Z. It uses Lang's film as a springboard for a surprisingly thought-provoking and constantly uplifting sci-fi tale of a conspiracy to take over a city using humanoid machines. In the romance between the half-human heroine Tima and the detective's nephew Kenichi, the film asks whether machines can love. This answer is an interesting take on Artificial Intelligence and Blade Runner, as the debate takes place within Tima herself, between her human nature and her robotic nature. The film opens with stunning visuals, showing the great city that, like Lang's Metropolis, exists on several levels above and below ground. We saw the skyscraper Jaegurat, a cluster of towers connected by bridges and brackets. The building appears to be a symbol of progress, but it actually conceals the plot of the evil Duke of Red to seize control of the city from elected officials. In the depths of Jaegurat, there is a throne suspended in a hall full of huge computer chips; this throne was designed for Dima, built by the mad Dr. Laughton, who died as Duke Eled daughter of a humanoid machine in the image. Tima's role is to take the computer's power And the imagination of the human brain is integrated into a force to own the city. Locke, the adopted son of Duke Red, hates the plan and wants to destroy Dima. He was jealous that his father preferred the artificial girl to his son, and he believed that the Duke of Red should take the throne himself. Other characters include an elderly detective who comes to the city to explore Jaegurat's secrets; his nephew Kenichi becomes a hero. The story is told with great energy; animation is more diverse than live-action in making catastrophic events understandable. There's a clarity and power to the mob scene at the start and the explosions and destruction throughout that's bound to disappear in a live-action movie. The animation owes more to Japan's manga tradition than mainstream American animation, both of which are considered art forms worthy of adult attention. In the image of Tima and Kenichi, the film follows the tradition of Japanese animation, with the protagonists, like children, with big eyes, innocent-looking and threatened. The other characters have more realistic faces and proportions, and do resemble Marvel superheroes (the contrast between the characters' appearances is unusual: imagine Nancy visiting Spider-Man). The backdrop and action scenes look like an animated version of the big-budget Hollywood thriller Devil's Quest series. The music is also Western. The introduction to the city features Dixieland (note: an early jazz genre), with Joe Primrose singing "St. James Infirmary" at one point and climaxing with Ray Charles' "I Can" 't Stop Loving You' (it's kind of like the We' at the end of Dr. Strangelove ll Meet Again"). The film is so visually rich that I want to watch it again and look at the corners of the frame and appreciate the details. Like all the best Japanese animation, it focuses on trivia. In one scene, an old man consults a book with occult knowledge. He opened it and read, and one page turned over by itself, and he turned it back. Moments like this may seem unnecessary considering that every action in an animated film requires thousands of images, but we still see some of it throughout the film. Filmmakers aren't content with plain live-action. Take the Coconut Hotel, which appears to be a lobby with a receptionist in charge of checking guests into old luxury railway carriages. 'Metropolis' is not a simple-minded animated cartoon, but a surprisingly thought-provoking, challenging adventure that explores the nature of life and love, the role of workers, the rights of machines (if any) , the pain of being rejected by his father, and the fascist frenzy behind Jaegurat. This isn't a remake of the 1926 classic, but a wild elaboration. If you've never watched Japanese animation, start with this one. If you love them, Metropolis will prove you right.

View more about Metropolis reviews