The vagaries of the bourgeoisie, the nouveau riche and the precariat are interwoven in this eye-pleasing Edwardian picture, whose sublime pulchritude is untainted almost 30 years after its birth, especially when regarding it on a cinema screen in its pristinely retro sheen (in Shanghai , presently several British classic films are enjoying a two-screening revival). It has everything we hope to savor in a prestige Merchant Ivory Production: Jhabvala's coruscating script that finely captures Forster's witticism and sophistication; the lush but well-modulated period hues and sets (with all the appurtenances, costumes, hairdos and skin-deep gentility); and an apt score that anticipates and follows every fluctuation of emotion in the hands of Richard Robbins. Collectively they reflect the stuffy but time-honored Britishness,redolent of a bygone era when being British connotes the ultimate one-upmanship.

But this revisiting is not entirely composed of positive vibes, one acute afterthought I cannot dissipate is that why I, personally, cannot find endearment in any of these characters? Tellingly, the Wilcoxes are snooty and callous, Hopkins' patriarch Henry is heartless, paternalistic and a hypocrite of the first water (though it is tempered with a ghost of ridicule by Hopkins' face-covering, laughter-eliciting affectation before unbosoming Henry's inner struggle); his eldest son Charles (our dearest Maurice, James Wilby) is a grotesque buffoon, who seems to belong in a very different movie. Even the ever so gracious, delicate, frail Vanessa Redgrave, who injects such delectable warmth, earnestness and sororal fondness into the story,her matriarch Ruth is desecrated by her naively unreconstructed inclination and her undue fixation of the titular dwelling, her tragedy is all underwritten though.

On the opposite spectrum, we have our heroines, the Schlegel sisters, Thompson's Margaret triumphantly puts the maligned repute of spinsterhood to rights, and her Oscar-winning performance is of supernal delight, gabby, savvy and not without her funny bone, Margaret appears to go with the flow without any expectation of marriage, she and her siblings have such envious communion together, why on earth she wants to alter that? Still, she cannot resist a chance to marry a minted, widowed businessman and condones his classist attitude and horrid conduct. It is sorrowful to see such a union persists in the end while what the film achieves to be is a hard-won jape on kismet.

As Margaret's younger sister Helen, Carter is exceptionally expressive, fiery, incandescent and over-eager to compensate for the mishap which she is partially responsible for, but also unfussy as a do-gooder. Her sympathy towards the hapless bank clerk Leonard Bast (West ) reaches the opposite extremity of Henry's cruel apathy. But the rub is, before offering counsel concerning one's livelihood, she, and Margaret, are ill-equipped with the tack of securing their source's accuracy, in a cunning way, it betrays the Achilles heel of the leisure class, being disengaged with the multitude, they are prone to take things for granted, they inherit lucre, in lieu of earning them.

The denouement of Leonard is disheartening, who has too much pride to take charity and cannot even sell his life dearly. But her wife Jacky (Duffet), absurdly employed in a plot twist and discarded henceforward. After watching their poverty-stricken misery, we are deprived of any knowledge about how she deals with the sudden passing of her husband, I don't know if the pertaining paragraphs exist in Forster's novel or they're abridged by the script, but as in the film, such treatment comes as a disappointment, one might surmise that jaundiced outlook of classism might extend from its characters to its scribe. I am not asking equal footing in the story, a tactful closure of a key character isn't too stretched a request.

Furthermore, there is a major continuity issue here, when does Henry gives in and let the sisters stay in Howards End after refuting it vehemently? Which might suggest some missteps in the cutting room, and even a casual viewer can easily notice several yawning cuttings from a crucial conversation scene between Henry and Margaret, so I double-check, editing is not among those accolades doting on the film by the Academy (it nabbed 9 nominations and 3 wins). How interesting a viewer's perspective changes through time and experience in relation to the same film, particularly those seasoned ones, I should do rewatches more frequently!

referential entries: Ivory's THE REMAINS OF THE DAY (1993, 7.5/10); A ROOM WITH A VIEW (1985, 8.6/10).

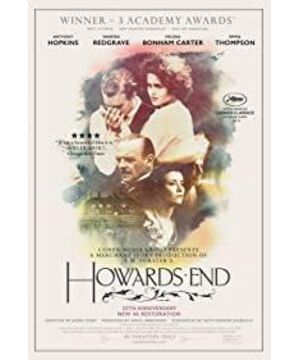

Title: Howards End

Year: 1992

Country: UK

Language: English

Genre: Drama, Romance

Director: James Ivory

Screenwriter: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

based on the novel by EM Forster

Music: Richard Robbins

Cinematography: Tony Pierce-Roberts

Editing: Andrew Marcus

Cast:

Emma Thompson

Anthony Hopkins

Helena Bonham Carter

Samuel West

Vanessa Redgrave

James Wilby

Nicola Duffett

Adrian Ross Magenty

Prunella Scales

Jemma Redgrave

Susie Lindeman

Joseph Bennett

Barbara Hicks

Simon Callow

Rating: 7.7/10

View more about Howards End reviews